East is east and west is west, and ne’er the twain shall meet.

Until you realize that Alaska is both the westernmost and easternmost state in North America. So much for ironclad theories.

What is an ironclad rule, however, is the safe operation of firearms—specifically with reference to a gun’s muzzle direction and the manipulation of one’s trigger finger. As regards the compass direction to which the barrel muzzle is pointed, it’s a matter of simple logic: If the weapon is inadvertently fired when it is pointed in a safe direction, there can be no other result than mere embarrassment. Nobody is unintentionally hurt or killed.

It’s as plain and simple as that.

But the manipulation of the trigger finger is a much more complex kettle of fish—for a variety of reasons.

First and foremost, curling all four fingers of a human hand is instinctual, genetically handed down since before the Dead Sea first became ill. From when cavemen dragged home their girlfriends; to the holding of rudimentary tools; to utilizing early weapons of war such as the club, sword or spear; Man adducted all four fingers on his hands as a grasping mechanism.

Then came the invention of the “hand gonne.” And no doubt during Day One of test firing, somebody had a negligent discharge with the firearm. It’s simply not an instinctual act to maintain a straight trigger finger until ignition is desired. The latter is a result of programming through training—up to a point.

Why “up to a point”? Because some firearms designs don’t “allow” a straight trigger finger if the shootist needs quick access to those specific safety mechanisms. And potentially compounding this problem are departmental or unit issue weapons, along with their attendant Standard Operating Procedures. These SOPs are, for the most part, beneficial for training individuals or troops for gunfighting. But they are not a panacea—nothing ever is when preparing for battle.

The above-mentioned manual safety design and positioning on some weapons often lead to one of two undesirable results: The operator prematurely trips the trigger before the gun’s sights are aligned with the target (the dreaded negligent discharge) or the weapon doesn’t fire when required because the shootist omits to disengage the manual safety prior to pressing the trigger.

Yes, I know: Colonel Cooper’s third of four safety rules states, “Keep your finger off the trigger until your sights are aligned with the target.” This rule is an absolute maxim, but equipment can sometimes hamper good intentions. There’s many a slip twixt cup and lip—or safety button and trigger.

For example, if you’re manipulating a Garand-style rifle safety or an old Remington 11 shotgun, you’re stuffing your grubby trigger finger inside the trigger guard to disengage the safety—dangerously close to the “go button.” That’s no excuse for violating Safety Rule Number Three, but often what can be programmed in a training environment is over-ridden by instinct on a muddy, rock-strewn hellhole of a battlefield.

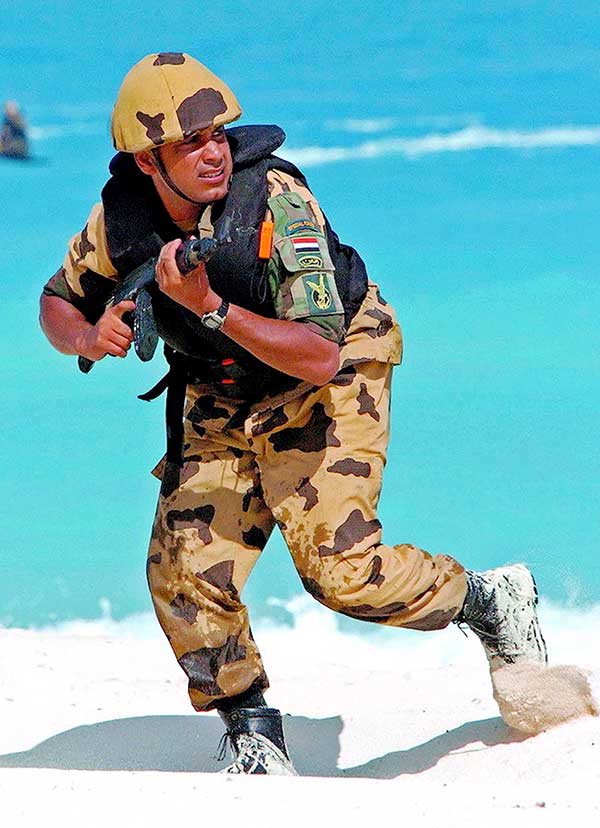

You can train ‘til hell freezes over according to your mandated SOP manual, but when it comes down to a firefight, you’ll do whatever it takes.

Often it is mandated by your administration that you will engage the safety mechanism during any advancing or withdrawing situations, and then you’re issued an M4 carbine, Remington 870 or Benelli shotgun, and Glock or Beretta M9 pistol. Two of the three have two different safety doohickeys, the shotguns requiring a crooked trigger finger to manipulate the safety button, and the pistols have no operator-manipulated mechanical safety. And no, a decocking lever is not a safety mechanism.

So what happens in battle? The trainee disengages the safety and maintains a straight trigger finger until shooting is required to avoid mass confusion when under duress. Sometimes an administrative SOP becomes interchangeable with another acronym—CYA.

Of course the manual safety morass becomes a non sequitur if, for example, you’re issued a Mossberg shotgun—be it a 500/590 series or a 930. Or a lever-action rifle, whereby the trigger finger is automatically distanced from the trigger when running the action.

Another big factor contributing to irresponsible trigger-finger habits is that we’re inundated with seeing “silver screen” trigger rectumitis. Whether it’s old Westerns with actors using single-action revolvers, or modern movies with index fingers on 15-round semi-auto pistol triggers at inopportune times, it soon becomes a matter of “monkey see, monkey do.” Not good.

When all is said and done, the criteria are the training of the trigger finger and safe muzzle direction. The problem is that you’re sanctimoniously being instructed to do this by people who’ve already experienced negligent discharges themselves—every one. And yes, that includes yours truly.

And you’re also often working under the mandate of administrators and bean-counters who decide what weaponry you carry. Unfortunately they often don’t understand the problem, or worse, don’t care whether you live or die.

If you can carry your firearms of choice, so much the better. It remains then to simplify complexities whereby you have mechanical safeties that enable a straight trigger finger when not firing (if possible), and practice, practice, practice—always bearing in mind that instinct is standing by to rear its ugly head and over-ride your training.

East may be east, and west may be west, but when operating firearms, it’s as well to remember there are 30 other compass points to consider…

Louis Awerbuck is Director of the internationally acclaimed Yavapai Firearms Academy. Course information and schedules are available at their website at www.yfainc.com.