These might have been on an IPSC IDPA target, photo-realistic target, or even a three-dimensional plastic target.

The instructor will often identify a desired aiming area and may even describe targeting the “medulla” as a “noreflex” shot.

As a physician, I have studied anatomy and treated people shot in the head. Let me share that perspective.

Table of Contents

THREE METHODS OF PHYSICAL INCAPACITATION

When we shoot an assailant, our goal is physical incapacitation. We want our attacker to stop attempting to harm us or others and to be physically incapable of resuming an attack. Physical incapacitation may occur in three ways.

Massive Blood Loss

The first results from massive blood loss, and this is the cause of physical incapacitation in most shootings. The blood loss results in too little blood flow reaching the brain to maintain consciousness. Any shot that tears a large blood vessel will contribute to this blood loss, so it offers a large target area. Unfortunately, this process is slow.

Shock that is due to blood loss is separated into four classes. Class I shock is due to the loss of less than 15% of blood volume—less than a quart. It is tolerated well and is similar to donating blood.

Class II shock results from the loss of 15 to 30% of blood volume, or about 1 to 2 quarts. The victim will be anxious and have an increased heart rate, but blood pressure will likely be near normal.

Class III shock results from the loss of 30 to 40% of blood volume, or about 2 to 2 ½ quarts. The victim will be confused, with an increased heart rate and lowered blood pressure.

Class IV shock results from the loss of over 40% of blood volume, or over 2 ½ quarts. The victim will be unconscious and death will soon follow if blood loss continues.

Class IV shock would be required to physically incapacitate an assailant. This is a large amount of blood and even with multiple well-placed shots will take significant time to achieve.

Spinal Cord Injury

The second mechanism for physical incapacitation is injury to the cervical (neck) spinal cord. This requires that the cord be cut or seriously damaged. It will result in instant incapacitation due to paralysis of the arms and legs (although partial arm control may persist with an injury near the bottom of the neck). With upper cervical spinal injury, the victim will die due to respiratory arrest.

The drawback is that the cervical spinal cord is small—about the width of your thumb. It is surrounded by bone and is likely moving. This isn’t a good target.

Brain Injury

The third mechanism is injury to the brain. This will almost always result in instant incapacitation if the brain itself is penetrated and damaged. It is a much larger target than the cervical spine. It is armored, but the thickness of the skull varies by location.

And nearly every gun magazine article I’ve read—and most instructors— get the fundamentals wrong.

MYTH OF THE MEDULLA

Most common is the Myth of the Medulla. The writer or instructor states that you must hit the medulla for a “no reflex” shot. A reflex is a response or action that occurs without conscious thought or intention. When I tap on your knee (patellar tendon) with a reflex hammer, a signal that the tendon and muscle are stretching goes to the spinal cord, and a return signal comes down to the quadriceps muscle, causing the leg to kick. That is a reflex. You do not think about it and cannot control it.

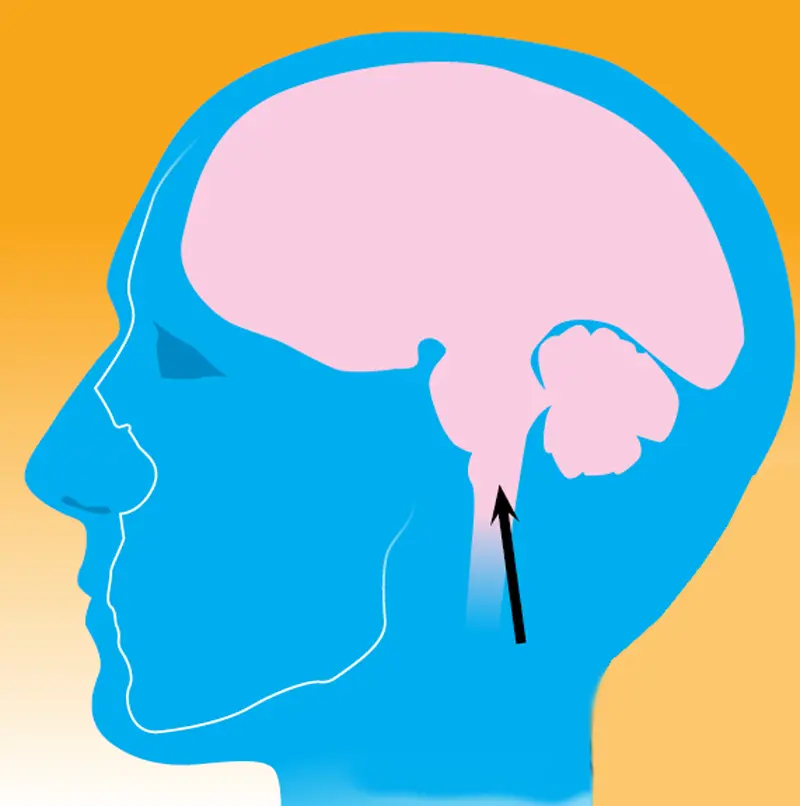

The medulla is at the very base of the brain, or brainstem. It helps control involuntary functions such as breathing and heartbeat. With traumatic brain injury, people may simply go completely limp. They may also have unconscious muscular contractions known as posturing.

If a criminal were holding a pistol pressed against a hostage’s temple and a rifle round impacted the criminal’s brain (even the medulla), he might have this involuntary contraction and the pistol might conceivably fire. If the pistol is instead pointed away from the hostage and the same rifle round penetrates the brain, the criminal will not have the ability to intentionally shoot the hostage.

I have searched the medical literature back to 1900 looking at gunshot wounds that penetrated the skull and did not result in immediate incapacitation. They are quite rare and typically involve underpowered handgun rounds or truly miraculous suicide attempts with a rifle. These rare cases involve a bullet that damages the edges of the brain (usually the frontal or temporal lobe) or that passes between the two hemispheres of the brain.

So why not aim at the medulla? Target size and armor.

WHERE NOT TO AIM

Look at the diagram of the skull and brain. Note that the medulla is at the very base of the brain, about even with the nostrils. Even a round entering through an eye will pass below most of the brain.

The thickest, toughest bones of the skull are those near the eyes and around the base of the brain. A round aimed at middle face is directed at the part of the skull that is the most difficult to penetrate. With a full-frontal shot, those bones can readily deflect projectiles, especially handgun rounds.

This is also exactly where most have been taught to aim: the triangle formed by the eyes joined to the nose. The brainstem is narrow and also changes position every time the head moves and turns, just like the cervical spinal cord. If you aim at the nose when the head is turned even slightly to the side, the straight-line path will miss the medulla and brainstem.

WHERE TO AIM

What would be an appropriate aiming point for the brain?

First, the bullet should impact perpendicularly to the bone of the skull, ideally where the bone is relatively flat. This will decrease the chance of the bullet skipping off the skull and not penetrating into the brain.

Second, try to penetrate the skull where the bone and soft tissue are less thick and avoid tough structures like the petrous bone at the base of the skull.

Finally, aim where you have the greatest room for error in shot placement and can still have the bullet enter the skull cavity and damage the brain, rather than simply impact the face or neck.

Assuming a full-frontal assailant, you should aim just between and above the eyes.

From the side (assailant looking directly to your left or right), aim just above the top of the ear. For other positions, you’ll need to mentally rotate this model, thinking about the position of the brain as the head turns. The key is getting the bullet to penetrate the skull and enter the brain, not the precise brain structure that is damaged.

Having seen the brim of a baseball cap deflect pistol and rifle rounds— and even 12-gauge slugs—keep in mind that bone and other objects may deflect a perfectly aimed shot. The brain must be penetrated and damaged for the shot to be effective.

Louis Awerbuck excels at making his students think about the orientation of the threat and how this changes where you need to aim. This is also true with the head.

If the threat is looking directly at you but upward, aiming at the nose will put the bullet’s intended path through the center of the brain. If the threat is looking downward, aiming for the upper forehead would be more appropriate.

We often hear the phrases “You will fight the way you train” and “Do enough repetitions that the skill becomes part of your muscle memory.” We go out and practice firing A-zone shots on the chest and head with our IPSC or IDPA targets, but photographic targets or humanoid models have the advantage of being anatomically correct.

Looking at the illustrations, it’s clear that what we are really conditioning ourselves to do is put that head shot right into the jaw, which is unlikely to result in our goal of immediate incapacitation. Get out to the range with some anatomically correct targets and try the shot placements outlined above.