These include some pistols (singleaction and striker fired) as well as most long guns (rifles, carbines and shotguns).

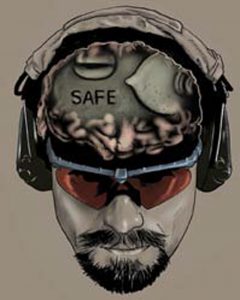

Enginerds and lawyers will consider the mechanical safety to be the primary safety, but I disagree. The primary safety lies between the ears, and the index finger on the strong-side paw is the application of that.

The mechanical safety is a secondary safety. More about that later.

Many pistols (and almost all revolvers) are without mechanical safeties. This is because they are in a holster when carried, and that holster prevents any items of gear from entering the trigger guard.

The long gun is carried by a sling and therefore requires the mechanical safety to avoid a non-controlled discharge.

Table of Contents

TYPES OF SAFETIES

The types of mechanical safeties vary as to application.

On single-action pistols (M1911 types, BHP), or striker fired (some S&W M&P pistols), it is a frame-mounted lever that when up is on safe, and when down is off safe.

Generally, Single-Action/Double-Action guns do not have safeties. They will have a slide-mounted decocking lever.

Using the M9 Service pistol as an example, the movement of the decocking lever is contrary to common sense, which is not much of a surprise, as the concept of an SA/DA pistol is nonsensical.

The lever must be moved downward to decock the gun, thereby putting the gun out of action. To place the gun in action, the decocking lever must be pushed up—a difficult but not impossible action.

Certain long guns (the Remington 870 and U.S. Carbine Cal .30 M1/M2 and M3) have a cross-bolt type safety that requires the user to push through from right to left to disengage the safety, making it hard for wrong handers.

Other shotguns, such as the Mossberg 500/590 series, have a tang-mounted safety that makes it ambidextrous.

BAD SAFETIES

A type of safety that borders on dangerous to use is the type that extends into the trigger guard. This is typified by the much revered U.S. Rifle, Cal 30 M1, and carried over to its short-lived brother, the U.S. Rifle Cal 7.62mm M14.

For these types, the mechanical safety protrudes into the trigger guard when on safe. To take it off safe, your trigger finger enters the trigger guard and pushes it forward.

The M1 entered service in 1936, and we know more—a lot more—about shooting now. It was a bad idea then, but it has been carried over into the Mini 14 type.

This can be somewhat overcome with training, but having the safety inside the trigger guard is an invitation to a negligent discharge.

Worse than the M1-type safety is that used on the U.S. Submachine Gun, Cal 45, M3A1. In this case, the ejection port cover is also the mechanical safety. A piece of sheet metal on the cover prevents the bolt from going forward when the cover is closed. The difficulty in getting this gun into action should have been obvious to the designer, but the disconnect between those who make and those who use is, in some cases, great.

LEVER SAFETIES

The most intuitive type of safety is the lever, and the M16 family of weapons remains the most ergonomic of U.S. service rifles/carbines. In this case, it is a selector, allowing you to switch between Safe, Semi and Auto (alternately, Burst).

It doesn’t transfer well into some other guns, though. The original MP5 subcaliber machine gun had a selector switch that could be manipulated only if you had E.T.-type fingers.

When attending MP5 school in the mid 1980s, I asked why they didn’t make a selector lever that was more ergonomically correct. The reply: “No one else complains about it.”

Gotcha’….

Eventually they were pressured into it, and the Navy selector was adopted. But for those who bought into the original gun, the users were faced with a dilemma. They could keep the mechanical safety ON and have to shift their grip in order to move it to fire, something that took more time than it should. Or they could move the mechanical safety to FIRE before entering the crisis site, and leave it that way for the duration.

Sadly, many did exactly that, and there have been some tragic negligent discharges as a result. Even worse, some of those initially trained on the MP5 transitioned to ARs, and they continued to use the faulty MP5 Tactics, Techniques and Procedures.

The AR type is a very ergonomic gun, and there is no reason not to have the mechanical safety on when the gun is not being used.

USING THE MECHANICAL SAFETY

1: ALWAYS ENGAGE IT

How the mechanical safety is used is often a subject of contention, with some extremes and a lot of common sense involved.

On one side of the coin, we have shooters executing a “speed safety”—that is, placing the safety on the millisecond the last shot goes downrange. This is the equivalent of “speed holstering” in competition circles.

The problem with training on a square range is that it prepares you mostly for what occurs on a square range. On that manicured patch of grass, you have paper targets—inanimate objects—placed at a specific distance from you. No matter how bad your shooting might be, the drill is over when you fire your last shot. On the two-way range, the bad guy has a vote in when the fight is over.

Doing it right, you shoot until the threat is no longer trying to make your wife a widow. That means you keep a sight picture and continue running that trigger as you follow him down and determine that he is no longer a threat to you or a third party. Only after you have ensured that the primary threats are down, and have scanned and assessed the immediate area will you engage the mechanical safety.

As an instructor, what I see—and see a lot—is that a great many will, when they move that selector to Safe, also switch their brain housing group to OFF. They drift into their happy place, oblivious to their surroundings, achieving the status of Situational Awareness Of A (expletive deleted) Rock—SAOAFR.

Lose situational awareness, lose the fight.

Another concept is to engage the mechanical safety at every opportunity unless you are actually shooting. On face value, it makes sense. But a problem that arises is that often—maybe more than often—when going to re-engage, our hero neglects to disengage the mechanical safety.

Instead, he presses on the trigger without result, and often defaults to zero.

In this case, he’ll look at the nonworking gun, apparently trying to make it work by osmosis.

This will be followed by a pursing of the lips, also known as Guppy Mouth.

It is not a malfunction, but rather cerebral flatulence.

Yes, this is a training issue, but the sad reality is that many of those who need training the most actually receive very little.

2: NEVER ENGAGE IT

On the other side of the coin is the school of thought that one never needs to engage the safety on an M4 type. I see this often in the shoot house, when shooters are far from their comfort zone, but also in graded exercises where shooters feel the need/desire to cheat, believing this will give them some advantage.

Of course the opposite is true. All they are doing is ingraining a permanent bad habit.

At EAG Tactical, we recently had a crusty and very senior Firearms Instructor in class who followed this path. We require that when in the Ready position, the trigger finger is straight and the mechanical safety is ON.

He flat wouldn’t do it. He said he had always done it that way and he wasn’t going to change. He had excuses for his actions, but they didn’t hold water.

RESPONSIBILITY

The bottom line is that you are responsible. The weapon is an inanimate object and requires human interaction to function. Without that interaction, the gun won’t fire.

Someone has to press the trigger or negligently permit the trigger to be pressed by insinuating a piece of gear against it.

The brain is the primary safety, and the finger is the application of the brain. It is active.

The mechanical safety is a secondary safety and is passive.

The gun is primarily a weapon, and the user’s responsibility is to employ it lawfully and correctly. This includes engaging the brain at all times when you are handling a weapon, and proper use of the mechanical safety on weapons that have it.

As I was writing this, I received information about a terrible tragedy that never should have happened.

A teenage boy had taken his 7mm hunting rifle out to shoot on his family’s ranch. Upon returning home, he unloaded the rifle before entering the house and placed the rifle on a table. His 17–year-old sister wanted to move the gun and picked it up, apparently with her finger on the trigger.

You can guess the rest. The rifle’s magazine was unloaded, but the chamber still contained a live round. The sister discharged a single round at near contact distance into the stomach of their 15-year-old sister.

She is alive, but the physical and emotional scars will persist for the entire family, probably forever.

This was preventable, but multiple mistakes were made by several people.

It is your responsibility. If you cannot accept that, you need to be doing something else.