NOT as well-known as the Sten or Sterling submachine guns (SMGs), the Lanchester reflected the scramble after the evacuation at Dunkirk to arm British troops to fend off the expected German invasion. The successful use of airborne troops by the Germans during the early days of World War II also emphasized the need for weapons to counter a possible German airborne assault on Britain.

Many British heavier weapons had been left behind in France, and the primary infantry arm was the SMLE Mk III bolt-action rifle. The Army had a limited number of Thompson SMGs and Bren LMGs, but the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Royal Navy desired SMGs to protect airfields and naval facilities.

Based on the need for speedy development of a submachine gun, the German MP 28, two examples of which were reportedly acquired in Ethiopia, was copied. It was determined that 50,000 copies would be required to meet immediate demands.

Sterling Armament Company was chosen to quickly produce prototypes, and two were ready by November 1940. Testing began immediately, and both proof and functioning trials were carried out. 5,204 rounds were fired with 26 malfunctions.

Most of the malfunctions were attributable to problems with the ammunition being used. The SMG passed accuracy testing as well as functioning after being placed in mud and sand.

Due to the immediate demand for the “Schmeisser” copy, it went into immediate production. Since George H. Lanchester had been the engineer who developed the weapon and supervised its production, it was designated the Lanchester Mk I.

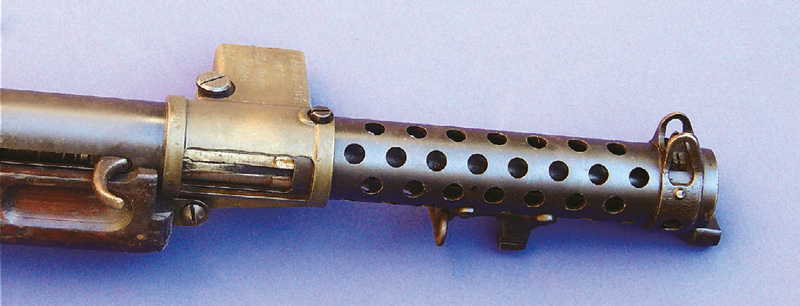

This was a copy of the German MP 28/II with some minor changes. It took a 50-round magazine that protruded from the left side of the receiver but would also take 32-round Sten magazines. The Mk I was replaced by the Mk I*, a simplified version that eliminated the selector switch of the Mk I, thus allowing only full-auto fire.

Originally, the Lanchesters produced as part of the order for 50,000 weapons were to be split between the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. But since the RAF had acquired 2,000 S&W 9mm carbines from the United States, most of the Lanchesters that would eventually be manufactured went to the Royal Navy. These Naval Lanchesters would remain in service for decades, as they were not declared obsolete until 1979.

I have seen production figures of 80,000 given, but other sources state that Sterling produced 74,579, Greener 16,990, and Boss 3,900. The latter two manufacturers were best known for producing shotguns.

At a time when the British armed forces needed as many weapons as possible and quickly, the Lanchester was expensive and time-consuming to produce. German weapons prior to WWII were often known for their extensive machining. As the Lanchester was based on the MP 28, it also required substantial machining.

Materials used in its construction were also expensive—for example, the solid brass magazine housing. Production rate for the Lanchester was about 3,400 units per month. As Lanchester production got underway, the Sten Gun, designed for cheap, quick production, was already under development. As a result, Lanchester production ceased in October 1943.

As the Lanchester was used primarily by the Royal Navy, its weight of almost ten pounds did not prove as disadvantageous as it would have for infantrymen. Its heavy design, with a sturdy wooden stock and machined steel receiver and breech block, plus its brass magazine housing, made the Lanchester a durable gun well suited for use by naval landing or boarding parties.

The stock was very similar to that of the SMLE Rifle No. 1, which gave it a familiar feel to troops trained on that rifle. It had a brass buttplate, which along with the magazine housing, made it more resistant to rust in naval service. Also making the Lanchester suitable for boarding or guarding prisoners, the Lanchester took the 1907 bayonet.

The Lanchester was an open-bolt blowback design with a cyclic rate of 600 rounds per minute. This rate was low enough and the SMG heavy enough that, when the selector switch was removed on the Mk I*, the weapon could still be fired readily in short bursts.

Somewhat like the Sten, the Lanchester used a locking cut in the receiver, which allowed engagement of the bolt in the cocked position. This safety was known for failing if the Lanchester was dropped on a hard surface. In naval service, decks and other hard surfaces were myriad.

As SMG sights go, those of the Lanchester aren’t bad, though the original tangent rear sight’s adjustment to 600 yards seems very optimistic. This rear sight was later changed to a two-leaf flip-up type for 100 and 200 yards.

The side-mounted double-stack, single-column-feed magazine is not known for its reliability due to bulging of the feed lips when loaded, though the fact it feeds from the left removes some of the pull of gravity of a bottomfeed magazine. The 50-round magazine is also quite difficult to load.

I have read that the British Commandos used the Lanchester, though in reading dozens of books on the WWII Commandos and examining hundreds of photos for a book I did about the Commandos, I have never seen one in use by them.

It is possible the Royal Marine Commandos had some or the Royal Navy Beachhead Commandos were equipped with the Lanchester, but overwhelmingly the SMG used by the Commandos was the Thompson.

One interesting comment on the Lanchester I heard recently is that it is a very Steampunk-looking weapon. Maybe so, but of the four SMGs used by the British in WWII—Thompson, Lanchester, Sten, and Sterling—it probably saw the least combat.

I have fired a large number of rounds through the other three, but only one or two magazines through a Lanchester. I found it heavy and not well balanced, though its weight and fixed stock did make recoil virtually unnoticeable, and its muzzle rise was relatively easy to control.

With its brass fittings and wooden stock, I do find the Lanchester a really interesting-looking SMG. Maybe I just like Steampunk!