M1928 “Navy” Overstamp. Thompson Sub-Machine Gun certainly has enormous CDI factor. At 33.75 inches long and 10.75 lbs. loaded, it weighs more than M4A1 Carbine with optic, white light and IR illuminator/laser aiming device, but uses substantially less effective cartridge.

The submachine gun (SMG) has been the odds-on favorite weapon of a great many people over the last 90+ years or so. Or maybe that is just what we have been programmed to believe.

Certainly the “entertainment media” will place an SMG in the hands of the hero, anti-hero or villain. Anyone worth paying attention to in film genres such as war, gangster, action and others, will use a submachine gun of one type or another.

They will range from the ubiquitous Thompson SMG (possibly the most recognizable and romantic weapon ever produced—used by G.I.s, feds and criminals alike) to MP40s used by snarling Nazi devils, though the propaganda flicks of the early 1940s had vismod TSMGs as MP40s in the hands of the dreaded Hun and even Japanese troops. Hollyweird apparently couldn’t get any German or Japanese sub-guns, and everyone knows that you must have SMGs if you want to fight a proper war, so TSMGs were substituted.

The 1970s transmogrified the TSMGs into Macs and Uzis, and in the 1980s, into MP5s.

Screen “heroes” who used the SMG were numerous: John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, Frank Sinatra, Steve McQueen, Vic Morrow—even Desi Arnaz. The list is extensive. How are we to believe that the SMG was not the absolute death-dealing weapon of all time, capable of mowing down hordes of Japanese, Chinese, Germans, North Koreans et al?

Reality may be a lot different than the screen version.

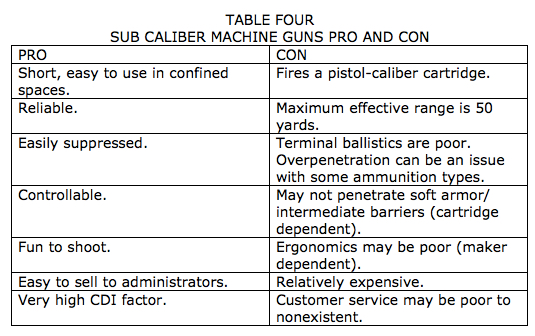

The term “submachine gun” is probably an incomplete name for this weapon, which should more accurately be called a sub caliber machine gun in that it fires a pistol caliber cartridge—most commonly a 9x19mm, but also in .45, 7.62×25, .380 and others—to distinguish it from real machine guns, which fire full-sized rifle ammunition.

The SMG is known by other names in other places and at other times—submachine carbine in the UK; machine pistol in Germany. The U.S. called the 5.56x45mm XM177 series a submachine gun, though clearly it was not. To add to the confusion, the S&W Light Rifle Model 1940 was a 9x19mm semiautomatic only weapon—which could accurately be called a sub caliber carbine. The S&W M76 was called a Machine Pistol by the factory. This verbiage confusion is not unique to the SMG family. The M1014 shotgun is called the Joint Services Combat Shotgun, when in fact it could be more accurately termed the Joint Services Guard Duty Shotgun—but I digress.

The SMG owes its existence to the failure of the world’s full caliber infantry rifles during the war to end all wars. These guns—possessing long barrels and sights graduated out to several thousand yards/meters—were clearly designed for long-range direct and indirect fire. Prior to the fielding of machine guns, infantry platoons were trained to use plunging fire on area targets.

MAC saw extremely limited service use (despite heavy advertising) but has found niche in SMG competition, proving that games and fighting are separate entities.

While wonderful for those wars fought in the past, these rifles were less than optimal in the trench warfare that existed during much of the war. Long, unwieldy, slow firing and slow to reload, the Germans saw the need for a select-fire, intermediate cartridge, magazine-fed weapon in 1918. Losing the war to end all wars put that project on hold until the next big war, when it came to fruition as the misnamed (purposely this time) MP44/StG44—the first true assault rifle fielded. The Russians—also big losers—saw a similar need at about the same time, but were a day late and a dollar short, and the AK series didn’t show up in battle until the Vietnam War.

The bayonet was a very big part of the infantry tool kit (due to the aforementioned slow rate of fire) and with that long blade affixed, the WWI rifle was something not useful for close quarter combat.

The Italians, Germans and Americans all ventured into the sub caliber game during the Big War. The Italians led the way with the first ever submachine gun, the Villar Perosa—a dual-barreled, magazine-fed 9mm that was originally for aircraft use, but the 9mm cartridge was not up to the task. Attempts at adopting it for ground use were largely unsuccessful. The Italians did field a more conventional SMG, the Beretta Model 1918, at the very end of the war.

The Germans also fielded an SMG in 1918—the MP18,I, a 9mm conventional type weapon fed from a 32-round snail type magazine. The Germans planned to arm a squad of six men in each company with the MP18,I.

The United States took a different route and attempted to field the Automatic Pistol, Caliber .30, Model 18 (commonly known as the Pederson device). Rather than go with a shorter, more compact design, the designer came up with a replacement bolt for the U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, M1903 that fired a .30-caliber pistol type round fed from a 40-round magazine. A specially modified receiver was necessary, and the rifle was semi-auto only.

Army Ordnance fantasized about the Pederson Device, stating, “As the enemy came charging across No Man’s Land, each of our soldiers would start firing with this miniature machine gun and the entire zone in front of the trenches would be covered in such a whirlwind of fire that no attack could survive…”

MK Arms Mk760 9x19mm SMG, short-lived copy of also short-lived S&W M76, which was copy of Swedish M-45 SMG, aka the “Swedish K.” It saw limited use in the military, and longer life with NYPDs Emergency Service Unit. Photo: Hilton Yam

As for offensive actions, the same observer stated, “…a line of soldiers advancing across No Man’s Land firing this device at the enemy trenches as they ran would make it extremely difficult to show his head or any part of his body. Of course, firing while running or walking would not be so accurate, but the tremendous amount of shots would more than make up for any inaccuracies, and the whole enemy trench system would presumably be smothered with a storm of bullets.” (“U.S. Infantry Weapons of the First World War,” Canfield)

There you have it, spray and pray—codified by the Ordnance Branch. While suppressive fire is a very valid technique, this Officer clearly put equipment ahead of tactics and was making statements not supported by facts. This isn’t unique, and similar statements by the Navy regarding Naval Gunfire Support, and Air Force regarding whatever is the most recent in the line of aerial-delivered ordnance, all of which are guaranteed to smother, blanket or surgically remove the offending enemy infantry/armor/command structure, never quite seem to make the grade either.

When I was a young and impressionable lad, I read an article in a gun rag of the day explaining the Pederson Device. Writing about the Philippine disaster in 1942, the author lamented that, if the Army hadn’t destroyed the Pederson Devices in the 1930s, those poor troops on Corregidor could have been airdropped a shipment of these wonder weapons and they would have been able to wipe out the entire Japanese assault force. Yup, all of them.

Of course he conveniently left out the fact that the rifles needed modification, and the fact that an 80-grain pistol type cartridge was not real effective in dumping men. But then he never did explain how any aircraft could have flown anywhere in that theater after MacArthur let the majority be destroyed on 08 December anyway. But hey, facts shouldn’t interfere with a good fantasy.

Very Short Barreled Rifles are perfect example of compromise between ballistic efficiency and handling/concealment. These two fill a niche for an agency, but would be less than optimal for a general purpose gun.

The popularity of a sub caliber machine gun in those days is easy to understand when compared with the infantry rifles of the day. A selective-fire gun, magazine fed, utilizing a pistol caliber round was lighter overall (though the weapons were similar in weight, ammunition was lighter), easier to use in close quarters, and didn’t need to be reloaded as often.

The downsides—ballistic inefficiency and range—were acceptable tradeoffs. The war ended before the SMG had an opportunity to prove itself, and the old guard went back to big long guns with full power cartridges.

During the interwar years, the Marine Corps was tasked with protecting the nation’s mail. In 1926 the Postmaster General purchased 200 M1921A TSMGs for the Marines guarding the mail trains. In 1927 the Marine Corps was conducting operations in Nicaragua against the Sandino rebels, and they brought 65 of the Postal Service TSMGs with them. Once again, the troops found that the issue infantry rifle was too long, too slow and insufficient for their needs. Other Marines used the TSMG in Shanghai in the late 1920s.

The Army also purchased a limited number of TSMGs for the cavalry in the early 1930s, and made it a standard weapon in 1938.

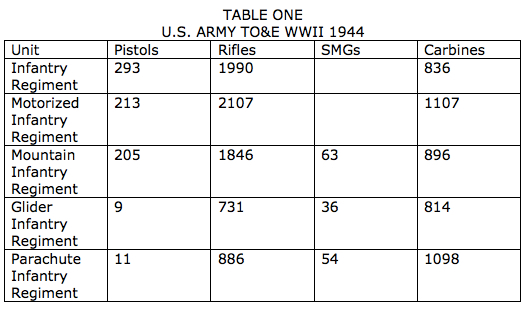

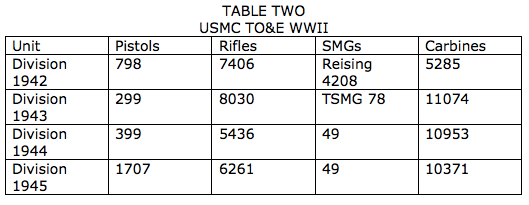

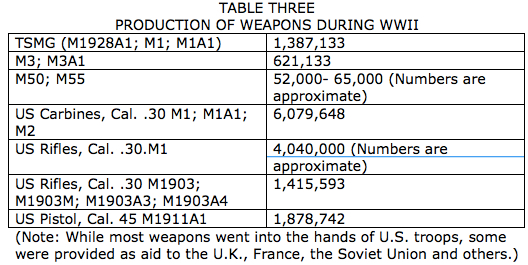

Contrary to the movies and TV shows, SMGs were not issued in great numbers to frontline U.S. troops. Rather they were issued, like M1 Carbines, to those whose job either did not require direct fighting (communicators, unit commanders and such) or who used other weapons (machine guns, mortars, tank crewmen and such).

Refer to the accompanying tables and note that the M1 Carbine was issued in far greater numbers then any of the SMGs.

The Marine Corps used large quantities of the M50 SMG prior to the adoption of the M1 Carbine, primarily to support troops. However, the Marine Corps Parachute Regiment did use large quantities of the M55 SMGs in the infantry squads.

On the other side of the world, some countries viewed events through blood-tinted field glasses. The Germans, faced with what seemed to be an inexhaustible supply of human targets in the former Soviet Union, needed something better than a shorter version of the same long and slow-to-operate rifle their fathers used 20+ years earlier. German machine guns—primarily the MG42—were spectacular in use, and the German philosophy of the infantry supporting the machine gun (rather than the U.S. doctrine of the machine gun supporting the infantry) worked after a fashion. There were, however, just too many of those Russkis to process efficiently. While the MP40 and other SMGs were available, the inefficiency of the 9x19mm round was recognized, and the MP44/StG44—the world’s first true assault rifle—was fielded. Unfortunately for the Germans, production never met their needs.

Deputy Pat Kelly of Dane County Sheriff’s Office fires his agency’s M1928 “Navy” Overstamp in Waunakee, WI. Everyone loves to shoot a Tommy Gun.

The Russians faced withering firepower from those massed German infantry weapons, and belatedly realized that the long and slow-to-operate rifle used by their fathers in the Big War was likewise as inefficient as the KAR98. With their industry in ruins, they opted for SMGs to fill the void. Several types were fielded, with the PPSh41 being the most prolific, though the follow-on PPS43 may have been a better gun. While any information coming out of that country is suspect, claims exist that over 6,000,000 SMGs were manufactured during the great patriotic war—and 5,000,000 of those were PPSh41s. The Red Army planned to have one platoon in each infantry company armed with SMGs.

The Soviet army developed a doctrine of massed automatic fire that existed at least until they lost the Cold War, and as soon as the AK-47 series came on line in the early to mid 1950s, the SMG was once again removed from front-line usage.

The Brits used a lot of SMGs during WWII. Their crushing defeat in France in 1940 resulted in the loss of an extraordinary amount of infantry weapons. They were desperate for weapons—any weapons—to fill the void, and the Sten submachine carbine helped keep soldiers armed with something.

During the Korean War, the NKPA, trained by the Soviets, likewise used large quantities of the PPSh41 SMG, which was more useful than the bolt-action rifles for raids and ambush patrols.

Why did the U.S. military almost ignore the SMG, while the other Allies and the Germans used it in great numbers? My feeling is that the U.S. fielded a full caliber semiautomatic rifle to the infantry—Army and Marine Corps—and a lightweight carbine for support troops while everyone else was still fiddling with bolt action rifles. These weapons were a significant improvement over what the rest of the world was using at the time.

The U.S. Ordnance people, generally fairly hidebound at the time, came very close to falling into what might have become a true assault rifle—the M1 Carbine series.

While the definition of a carbine is fluid and lost in history, one valid description is that a carbine is essentially identical to the contemporary service rifle of the period with the exception of having a shorter stock and barrel. Consider the M16A4 and the M4A1 Carbine, and you’ll get the idea. Both are chambered for 5.56x45mm, and the carbine is shorter than the rifle.

The M1 Carbine was an anomaly in that it was a completely different gun, with a different operating system and a different cartridge. While the M1 Rifle fired a .30-caliber cartridge (7.62x63mm), the M1 Carbine fired a .30-caliber cartridge that was significantly shorter (7.62x33mm). Looking more like a pistol cartridge, the M1 Carbine launched a 110-grain ball projectile downrange at 1,970 feet-per-second (fps).

The M1 Carbine looked like a conventional rifle with the exception of a detachable 15-round magazine. Designed to replace the pistol (an excellent idea, but it never really accomplished that goal) and to provide those support troops with a viable defensive weapon, it was an attractive system. Lightweight (compared to the M1 Rifle and SMs), it was easy to shoot and had sufficient range to engage the enemy at short to intermediate ranges.

In 1943 the M1 Carbine was modified into a select-fire weapon—the M2 Carbine. While few saw service in WWII, it saw a lot of use in Korea and Vietnam.

There were many complaints about the .30-caliber carbine failing to put people down. Indeed, while growing up, several of my cousins had just returned from Korea and told stories that were similar in context: “I emptied a whole clip (sic) into a (pejorative slang expression for the enemy at that time) and he never went down.” While the ball ammunition is not terrific, my belief is that a great many of these stories were based on perception rather than reality. Combat is an interesting study, and unlike police work—where a great majority of the incidents are over in a few heartbeats and a lot can be recreated forensically—combat can last for a long time, and will generally involve multiple moving parts. I am not stating that I doubt what people say—just that what they say and what they truly believe may not necessarily be what happened. Their perception of the event, and the actual event, may be widely separated.

Dr. Kevin O’Neil at Pat Goodale’s West Virginia facility with his MP5HD2, which has integral suppressor and may well define this generation of sub caliber machine guns.

I once had a very high-strung point-shooting advocate in a class. He was adamant about unsighted fire, so I gave him an opportunity to fire a single brain shot from one meter. He focused on the target, elevated the carbine and fired a shot that never hit the paper. While continuing to look at the target, and while never moving the gun, he immediately fired a second miss before I could stop him. He stated, very clearly, “I can’t believe that happened.” I’ll broadly assume that what he meant was “I can’t believe I missed!”

I have taken a great number of people through the shoot house who, at ranges of six feet, never once struck the target. During the brief back, they would invariably state, “I can’t believe I missed him!” Yet they did miss.

Knowing how difficult it is to hit a moving, breathing human at close range, I now believe that in some instances what the storyteller really meant was, “I emptied a whole clip (sic) at him,” and what the teller believed were solid hits may have been wide misses.

A long time ago in a country that no longer exists, I bumped into a mortarman who was carrying a K-50 (a modified PPSh41 SMG). At a distance of only a very few feet, he fired a very long burst at me. His thought process at this time might have been along the lines of “Hey! What’s up with this? I have to be hitting him. I mean, I can’t be missing him at this range!”

He didn’t hit me (for which I am very happy) and, whatever his thoughts at the time, they were his final ones as an earthly oxygen consumer.

No, the M1 Carbine wasn’t a death ray. However, using civilian soft point ammunition, that same gun in police hands was (and is) a very capable weapon.

During the Vietnam War, some units started off with SMGs. The Marine Corps Force Reconnaissance people carried the M3A1 to war initially, but soon changed over to M16s.

In the early days of MACVSOG they needed to be deniable. To that end they initially carried Swedish M45 SMGs (aka the Swedish K), but when the nature of the war changed, they went to the XM177 series carbine—though it too was given the nomenclature of submachine gun by a bureaucratic thimble brain.

A resurgence in the use of SMGs in the 1970s was a direct result of the Direct Action mission in use by some in the military, paramilitary and some police organizations. In Extremis Hostage Rescue (IHR) had become an issue as the result of Muslim extremists’ war against the West, as well as more sophisticated and violent criminal operations in the United States. Some high profile units (think SAS here) accomplished some fairly excellent ops against the vermin, and the MP5 SMG was thrust into the limelight—and the armory of all with the potential for similar mission requirements.

The MP5 rapidly replaced the aging but still useful M3A1 SMGs in the hands of some CT and deep reconnaissance units in the military (some were allegedly referred to at the time as the “Grease Gun Gangs”), but the M3A1 remained in the CT community.

The Colt 9x19mm SMGs were used by some units. Retired Marine Col. Bob Young was at Security Forces when they worked out a deal with Colt to replace a number of worn out and suppressed Colt SMGs for a like number of new ones. These particular guns were put to good use for CQB by the Security Force Marines in Panama during Operation Just Cause.

Bob states that during Just Cause, these Marines also brought their M16s along with them in the vehicles, paying attention to lessons learned from some units during Urgent Fury. A 9×19 SMG is not very efficient when fighting against people at 100+ meters who are armed with AKs.

Some smaller sub caliber machine guns (euphemistically called Personal Defense Weapons (PDW)) are still used for Protective Security Details (PSD) (MP5K, P-90 and some others). The greatly reduced size of the PDW means easier carry, but not always better ergonomics, and some of the cartridges used in these weapons are anemic against personnel not wearing soft armor. One offering was used by several domestic tactical teams (the operative word being “was”). Of the current crop, the KAC offering, in 6x35mm, may have a round that shows some promise. The gun is flawed with a non-adjustable folding stock. While obviously a compromise to enhance transportation and portability, you once more wind up with a length of pull that is too long.

The PDW may (like the DA pistol) be a good example of a solution to a non-existent problem. The niche for the PDW is extremely small, and aggressive marketing won’t compensate for a poorly designed product or substandard ammunition.

Some protective teams use 6-10.5-inch barreled ARs. There is no doubt that the muzzle blast from these guns is ferocious, but the ability of the 5.56x45mm round to perforate soft armor is a fair trade off. Critics of these very short-barreled rifles rightfully claim that the 5.56mm round is also ballistically challenged when leaving such a short barrel. There is no free lunch except at the homeless shelter, and I prefer not to hang there. The 5.56mm projectile may not yaw or fragment from that barrel, but the recipient will not feel any better after ingesting a round or rounds at intimate distance either.

In 1998 there were 658 SMGs in the Marine Corps. 619 were MP5Ns and 39 were non-standard SMGs: MP5A3s, MP5SD3s, Stens, and a few Uzis. The MP5s were generally all in the Force Reconnaissance community as a CQB weapon. When the Marine Corps received the M4A1 SOPMOD that same year, they kept a few MP5Ns (approximately 15 per company) and turned the rest in.

The SMG is a specialized weapon that fills a particular niche in the arsenal. The SMG is on the list of approved weapons for use within certain areas. The 5.56x45mm round, traveling at supersonic velocities, is contraindicated in these spaces for some very valid reasons, and while the 9×19 is clearly inferior in the anti-personnel role, it is a lot better then using verbal judo.

Additionally, 9x19mm is easier to suppress, and the use of suppressed SMGs has paid off very well in specific circumstances. The hostage job in a Good Guys store in CA awhile back resulted in the loss of several hostages to Vietnamese gangsters. However, many more would certainly have died if the emergency assault team, armed with suppressed MP5s, had not entered from a storeroom and eliminated several of the bad guys. The team stated that the perps were unaware of where the fire was coming from.

SMGs are generally very reliable, and most problems with them are magazine related. The Thompson SMG is one of my favorites, though it has its drawbacks. Heavy, with a long length of pull and poor ergonomics, I have never had a malfunction with any of the ones that I have fired. The M3A1 was ugly, but if you had good magazines it ran well. The MP5s are certainly dependable, but lack the ergonomics of the Colt SMG, and suffer from horrible customer service. Perfection exists only in the mind of the advertising wienies.

The sub caliber machine gun was born in the trenches of Western Europe and rose to its ascendancy as the hordes of Soviet Infantry swept westward to grind the German people into submission. It had a brief moment of reanimation as a counter-terrorist weapon and status symbol among elite (and wannabe elite) forces.

The same values that made the sub caliber machine gun so attractive—easier to handle, magazine fed, select fire—led to its decline when the 5.56x45mm carbines added lighter weight (relatively speaking) and greatly enhanced ballistic efficiency to the mix.

Sub Caliber Machine Guns are great fun to shoot, and there is no doubt that they have a very high CDI factor. I have carried and used the M3A1, M1A1 TSMG, M76, MP5SD3, MP5A3, MP5N, and once, for a very short while, even an MP40. I enjoyed shooting them all, but the deficiencies in terminal ballistics and range (as well as ammo resupply) gave me significantly less than a warm and fuzzy felling. Given a choice, I would take a 5.56x45mm AR carbine (of any barrel length) over any pistol-caliber machine gun ever built. Of course, that doesn’t mean I will ever pass up the opportunity to shoot one any chance I get.

Sub Caliber Machine Guns will always have a place in the shooting community, though it may be more on the collector’s side than operational. The tool used by a true warrior is less important than that which lies in his heart.

[Pat Rogers is a retired Chief Warrant Officer of Marines and a retired NYPD Sergeant. Pat is the owner of E.A.G. Inc., which provides services to various governmental organizations. He can be reached at [email protected]]