The U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, M1 (often called the M1 Garand) is inextricably linked to the battles of World War II, and for good reason, it being so advanced relative to the other service rifles of the era.

What many shooters do not know is that the first major U.S. ground offensive of the war was fought almost exclusively by Marines carrying the M1903 Springfield.

I’ve often wondered just how much of a disadvantage this was or wasn’t, and set out to form a hands-on opinion.

Table of Contents

THE ‘CANAL

In the summer of 1942, the U.S. and its allies were on their heels. The invasion of North Africa was in its earliest planning stages and the nation was struggling to mobilize after years of denial and meager defense spending.

The Japanese had gobbled up territory and resources all across the vast Pacific after their victory at Pearl Harbor—one of many as the Emperor’s forces rolled like a wave across U.S. and Allied possessions. The discovery of an airfield being built on the island of Guadalcanal—within bomber range of Australia—rushed us into action.

The 1st Marine Division landed in August 1942 and began an epic struggle, which lasted for over six months, to take the island. The Marines and Japanese fought back and forth across miles of jungle and rainforest, both sides realizing the stakes, while equally desperate fighting played out overhead in the skies and at sea.

The Springfield-armed Leathernecks carved a place in history and turned the tide of the Pacific war. With the loss of the ‘Canal, the Japanese took no additional ground and reverted to the defensive, as our forces fought them island to island back to their homeland.

Beloved Springfield, U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30-’06, M1903. Marines who stopped Japanese advance at Guadalcanal were carrying rifles like this, although later battles were fought with the M1 Garand.

THE RIFLES

The Marine Corps is by orders of magnitude the most conservative branch of the military and perennially the poorest, and this was even truer in the era leading up to the war.

The Corps had passed on the Garand when it was first adopted by the Army, being satisfied to let the doughboys gamble on the new technology and shake out the kinks. The Marines tested and re-tested the M1, debates raging internally on its merits and demerits.

When the decision was finally made to adopt the rifle, the Corps found itself behind a backlog of Army orders with the expansion of the forces. Thus, as Marines boarded transports for the invasion of a far-off island none had ever heard of, they were armed with the same rifles their fathers had established the Corps’ reputation with at Belleau Wood, where the Germans began taking effective fire hundreds of yards farther than expected.

Springfield ’03 is a smooth-handling bolt gun. Next round is locked into chamber with Magtech brass still rising. But at jungle distances, 1.3-second splits could make even the staunchest advocate wish for a self-loader.

M1903 Springfield

The Springfield is a Mauser derivative with some Yankee refinement. In fact, the U.S. ended up paying hefty sums for various patent infringements. It is an 8.7-pound bolt-action .30-’06 with a five-round internal magazine fed by stripper clips.

At the time of the battle, the USMC rifles had the traditional open battle sights with a flip-up ladder that took the rifle to distance. The battle sight has an exceptionally narrow notch and a particularly fine front sight and was set to 547 yards, the theory being that the shooter could hold at the belt line from muzzle to way out there, and the upright man target would be in the danger space of the round’s trajectory.

The ’03 had a storied reputation for accuracy, and only lightly modified service rifles set records at the 600- and 1,000-yard lines of Camp Perry regularly. In practice, the battle sight puts the round quite high from the muzzle out to practical combat ranges, necessitating a significant offset “hold-under.” The Corps had modified sights in the interwar period to a sensible 200-yard zero, but many of the rifles issued in the rapidly expanding Corps had the traditional 547-yard zero.

The Marines who were hurriedly formed, trained, and shipped to the “South Pacific” were well grounded in classical marksmanship with their rifles. An expert rifleman’s badge brought additional monthly pay and esteem in a service that prided itself on its shooting. The Marines had no formal training in close-range fire, as training curiously skipped from 200-yard standing to use of the bayonet and buttstock in hand-to-hand combat.

Bayonet likely brought comfort at night and in close when the action couldn’t be worked as fast as the targets were charging.

M1 Garand

The M1 is a 9.5-pound gas-operated semiautomatic also chambered in .30-’06 and fed from an en-bloc clip of eight rounds into an internal magazine. The weapon had largely shaken off initial teething issues by the time the first rifles started showing up on Guadalcanal, and it was considered rugged, reliable and more than accurate enough for its intended usage. As soon as Army units began to rotate into the lines, Marines started stealing any rifle they could get their hands on—significant testament to its utility. It is perhaps one of the only times in military history when troops approved of a heavier piece of gear.

LET’S SETTLE THIS

I spent months preparing with the ‘03 for the shooting while I researched and settled on what the appropriate drills would be. In a 1940 field manual, I found that the rifle training for recruits at the time called for tying the trigger back with twine and working the bolt vigorously, with a goal of cycling the action 20 times in as many seconds. This was done prone with the support of a loop sling, meant to prepare the shooter for rapid-fire strings of fire or to engage a line of assault moving from an opposing trench/position. I focused predominantly on standing and worked up to the point where I was incorporating the trigger break into the cycle.

I honestly did no practice with the M1, assuming it would be most illustrative of the Marine who was familiar with the Springfield but had “acquired” a Garand.

Army reinforcements brought first M1s onto Guadalcanal. Marines were instant fans, appropriating every rifle they could.

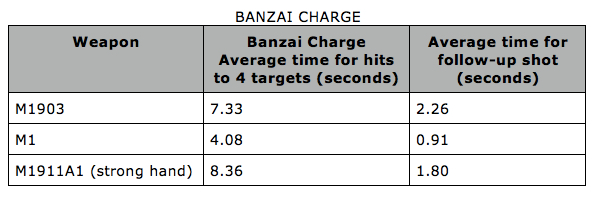

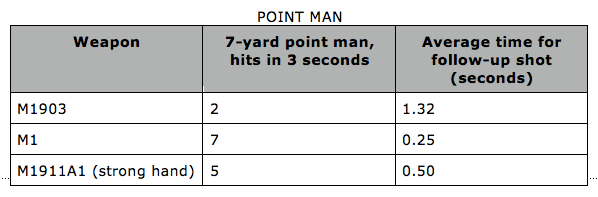

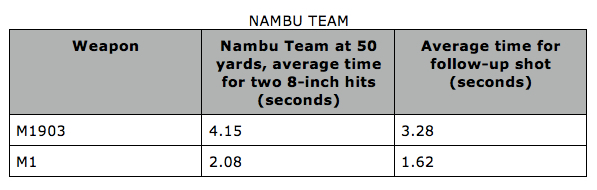

For the shooting, I decided that three drills would represent the most common employment of the rifle at Guadalcanal. First: repelling an attack, shooting multiple targets across a frontage as if they were part of a Banzai charge coming to my sector of the line. Second: multiple shots into a single target up close for time, as in a point man on patrol encountering a Japanese soldier unexpectedly. The final scenario was to engage a simulated Nambu machinegun crew or pillbox from kneeling as in the attack.

The rifles were representative samples of each, the M1 with late war features but nothing that alters the performance from the period correct version. Both were fired with a Sellier & Bellot load imported by Magtech that is a dead ringer for the M2 ball used throughout the war and afterward.

In zeroing the rifles, each shot well, clustering the MagTech ball into two-inch groups from prone with a loop sling at 100 yards—how the Corps intended the weapons to be fired, by gawd!

All shooting was done with a Magtech imported S&B load that is virtually identical to the issue M2 ball.

BANZAI!

Guadalcanal has an exotic landscape of dense jungle, canopied rainforest, and fields of head high or taller kunai grass. These elements combined to severely restrict visibility and range. Most accounts indicate 30 yards as a long shot in the almost exclusively close combat.

After the Marines had taken the airfield and established a defensive line around it, the Japanese launched a series of attacks to retake the field. Wave after wave formed at the edge of the jungle and charged the short cleared distance up the ridge to try to break the Marine line. Therefore the drill scattered four silhouettes arranged from 17 to 22 yards across a frontage about 20 yards wide. On the buzzer, I mounted the rifle and worked the targets as quickly as possible.

M1911A1 compared well in two scenarios, verifying its standing and reputation for close-in work.

The Springfield shoulders well and has a nice balance. But attempting to work the bolt while driving the rifle hard in a swing to the next target was challenging. In fact, even after all my preparatory effort, on one run I short stroked the action, extracting and ejecting the empty but failing to retract the bolt that last 1/8 inch required for the magazine to present the next round for feeding. “Click!” followed by reaction and working the bolt again brought that split time to a devastating 4.7 seconds.

The sights were not prominent enough for speed. I found myself running the front sight much like the bead of a shotgun and relying on a good mount to hit. Since the targets were relatively close and large, this resulted in better hits than expected, with all impacts in the vitals. Even under the mild stress of a timed drill, I could not make myself slow to find the sight in the notch and offset the bullet’s rise.

The M1 never slowed down. The sights are a great feature of the rifle and allowed me to look through them and press shot after shot, driving the front sight to center chest, fire, and then swing with the recoil to the next victim. The table tells the tale, but better hits in much less than half the time for follow-up shots are significant. My unfamiliarity with the M1 led to slightly slower mounts and first shots.

Out of curiosity, I incorporated a 1911A1 .45 into the drill, firing it strong-hand only as it would have been used according to the training at the time. Presentation to the first target and breaking the seven-plus pound representatively awful trigger lagged a little over a second behind the ’03, but the rest of the charging team each received good hits half a second faster than with the Springfield.

The results seem to explain the near-reverence that Pacific vets hold for automatic weapons. After this, I can picture that if I were trying to stop a charge by working a bolt gun, I would genuinely appreciate what a BAR or M1917 Browning .30 was doing.

ON POINT

Patrols crisscrossed the island for months, with chance encounters happening up close and fast. Marines put shotguns and Thompson or Reising .45 SMGs up front whenever possible, but the rifle—as always—was the main tool.

To replicate a point man reacting to an unexpected contact, I set up a silhouette at seven yards and worked it as fast as possible for time. I figured three seconds was a reasonable time frame in which the affair would probably have left one or the other incapacitated or out of the open and seeking the jungle’s concealment.

The ‘03 averaged a second and a third to break the shot and wrangle the bolt through the cycle. I desperately wanted to break under one second, but it wasn’t to be. I am confident that the average Marine in the line was unlikely to work it much faster. The groups were acceptably clustered in the vitals, but looser than I would have liked. In fairness, the Springfield is a smooth-cycling bolt gun and, in a head-to-head race with the Japanese Arisaka used throughout the war, it would win hands-down.

This says it all. Ability to quickly pour .30 caliber into a fight made the M1 stand above every other contemporary service rifle.

The M1 was confidence inspiring. The shots ripped out at quarter-second intervals and piled into a fist-sized group. On the last timed run, the Garand emptied all eight shots within the three seconds.

The .45 auto emptied the magazine into the chest in just under four seconds from strong hand, consistently putting five hits within the same time that the ’03 got two. This may shed some light on why the .45 was so appreciated for close-in work among the fighting holes at night for ‘03 armed hands.

For those wondering why the need for multiple shots from a .30-’06 or .45, I understand and it is a valid question. Surprise close-range encounters often have misses, poor hits, and uncooperative targets who don’t submit. Consider this passage from Army Lt. Col. George’s Shots Fired in Anger, from one of the last Banzai charges his battalion faced on the island:

“[The Japanese soldier] was charging the two men, his arms and body cocked back to deliver a piston thrust to his bayonetted rifle…. [Two U.S. soldiers] pointed their Garands … at his chest. Then they pumped the triggers until both clips were ringingly ejected from the receivers. They lowered aim to keep the stream of metal pouring through him as he fell to his knees…. This continued fire was not hysterical—not a waste of ammunition. That Jap was alive and dangerous until perhaps the last two rounds were fired.”

In hindsight, the results call into question the Corps’ reluctance to embrace the M1. However, the Corps was looking at the issue with a lens of one shot being enough per threat and the eternal hand-wringing about wasting ammunition and supply chains.

And surprisingly, for all the exhaustive testing the USMC put the M1 through, the only close-range consideration was whether the rifle would function properly with a bayonet mounted while firing at a severe downward angle, as in firing down into a trench. Formal training began at 200 yards and went beyond, leaving experience and knowledge to be gained up close in actual combat.

NAMBU

In the offense on Guadalcanal, Marines trying to cross any small space of open ground or a linear danger area such as a creek would often have to eliminate the ever-present Nambu team or pay dearly.

For the final drill, I placed two eight-inch steel plates at about 50 yards, spaced to replicate a gunner/A-gunner’s exposed heads for the much-respected Nambu machinegun. The shots were taken from kneeling without the aid of a sling.

The recoil of the .30-’06 had been noticeable but barely distracting in the first two drills. From a knee, the lighter-weight Springfield rocked the position in recoil. I had to hold under the plate to get the hits due to the awkward battle sight trajectory, and this led to several misses on runs (discarded from averages).

The M1 pushed my position a little, but the gas operation and extra weight took just enough out to allow the rifle to recover easily onto the next head plate. The far better sights also let the first shot break in half the time as the ’03.

SANDS OF IWO JIMA

Stateside production of the M1 is an incredible story of its own, and soon after Guadalcanal, supply began to meet military-wide demand. The Corps fought its way across the rest of the Pacific carrying the M1, and images of Marines and M1s are seared into the national consciousness.

However, the brave men who stopped the Japanese advance in August 1942 were closing the book on the 1903 Springfield’s service as a primary arm. I have an even deeper respect for them after comparing the two rifles.

SOURCE:

Magtech Ammunition

(800) 466-7191

www.magtechammunition.com