My first reloading experience was in Dad’s basement shop, watching, then helping him reload .38s and .30-06. I was about ten, and I still have the trophy he won at a local DCM (Department of Civilian Marksmanship) match with his handloads.

Later, during my toolmaking apprenticeship, I moonlighted for a gentleman who made bullet-making dies for the benchrest competition elite. Most top shooters used Bob Simonson’s dies, including the founder of one of today’s premium bullet companies. I learned a ton about accuracy from Bob.

I’ve reloaded every caliber I have used, but mostly .45 ACP; still my volume leader. With .45 ACP, I pick up brass, tumble it (sometimes I don’t even do that), and feed it into my Dillon progressive reloader. Reloading bottle-necked rifle cartridges, though, is more involved.

My .223 handloads carried me through a period of NRA High Power shooting culminating in a not-shameful showing at the Camp Perry National Matches, and trips to South Dakota to, shall we say, help manage the prairie dog population.

A note on shooting skills: Every American who wants to be called a rifleman should go to Camp Perry at least once, or shoot some local High Power matches. More might be learned in a season of competition than in a decade of informal range days. It might not seem “tactical,” but becoming intimate with your gear and honing marksmanship translates well into anything you do with a rifle. My best results here would not be impressive to top High Power shooters, who shoot 10s and Xs at 600 yards—with iron sights!

Why did I stop reloading .223? Match weekends and rodent safaris became less frequent. I got involved in police training, where we definitely stress precision, but there is no need to put all rounds into the same hole. Quite honestly, for most of this training, fodder-grade ammo gets it done.

The other reason I stopped reloading .223 is that it can be a little tedious.

But the savings are significant. That’s part of the reason I got back into reloading .223. Also, I simply wanted to again feel the pride of loading my own ammo that would shoot boast-ready groups, and to facilitate getting my bullets-clangin’-distant-steel fix.

Table of Contents

.223 Ammo “SAVINGS”?

Shop for .223 or 5.56 ammunition featuring 69-, 75-, or 77-grain OTM (Open-Tip Match) bullets and you’ll be looking at nearly a buck a round, and up to $1.50 or more. Even at $1.10, that’s $1,100 per 1,000 rounds. The cost of components for 1,000 rounds is under $340:

- 3.5 pounds Alliant RL15 powder: $90

- 1,000 Nosler 77-grain bullets: $220 (I found them on sale for $190)

- 1,000 primers: $25

Brass—no cost, as in, I had it already. Total: $335, meaning $765 saved.

“But what about all the time you had to put into it?” you ask, and rightly so. Once I got my tools and procedures dusted off and a new set of Forster dies set up, my time invested in 1,000 rounds was about a minute a round, or 17 hours. Distributed over enough long Michigan winter evenings, it’s not as bad as it sounds.

How much time would one have to put in at work to make the additional $765 to just go out and buy that ammo? $765 savings divided by 17 hours is $45/hour. I look at it like this: I’m paying myself $45/hour instead of someone else. And that 17 hours can be pared to about five. More coming on that.

I picked the 77-grain weight because across several brands it is universally an accurate weight to work with in .223. The extra weight reduces the effect of wind, especially when going beyond 200 to 300 yards. Few bullets heavier (and therefore longer) than 77 grains can be loaded in .223 without exceeding the maximum cartridge length, which prevents feeding them from the magazine of an AR-15.

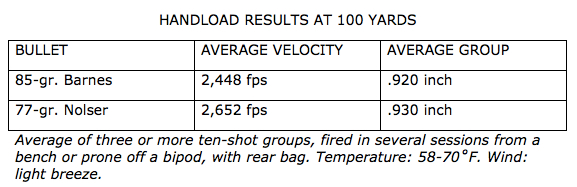

The Barnes 85-grain Match Burner can be loaded short enough; I tried it too.

MY PROCESS

Case Preparation

- Tumble brass.

- Resize and deprime brass. Cases must be lubed. The lube has to come off.

- Wash brass in hot soapy water to remove lube, including a quick brushing-out of the case mouth. Rinse and dry the brass. I don’t know anyone else who does this, and brass will be re-tumbled anyway, but I like getting the lube off so the cases aren’t slippery in subsequent operations.

- Trim brass to length—an absolute must. Resizing lengthens the case slightly, and if it gets too long for the neck of the chamber, reliability will suffer. Safety too, as the chamber may squeeze the case mouth down onto the bullet, making it harder for the bullet to exit the case, driving up pressure.

- Deburr, chamfer case mouths inside and out.

- Brush out primer pocket bottoms to remove carbon left from previous firing. Many people skip this, but I believe it’s worthwhile for more positive and consistent primer seating. A special tool makes it easy.

- Remove crimps from primer pockets of once-fired military brass. It’s tempting to skip this, but if you do, it will be nearly impossible to get a fresh primer seated. You can chamfer it out with the case mouth deburring tool, or use a swaging tool offered by several companies.

- Re-tumble brass, subsequently inspect cases for chunks of tumbling media stuck in flash holes, and poke them out.

Loading

- Insert new primers. I sometimes do this with a hand-priming tool as it gives more “feel” to the process. This tells me right away if a case has a loose primer pocket—one that may lose the primer upon ejection, dropping it into the rifle and causing a malfunction. Such cases may be common when using range pick-up brass of unknown provenance. This condition is usually caused by 5.56-spec ammo, which is a tad hotter than .223 commercial-spec being fired in a commercial-spec .223 chamber, commonly and inexplicably found in many brands of AR-15. It is advisable to know the source of your brass.

- Drop powder charge into case. I use a Forster benchrest-style powder measure for this.

- Seat bullets. I use a seating die with a spring-loaded sliding cartridge guide that helps ensure perfect alignment of the case and bullet before the bullet enters the case neck. Several companies offer this style of seater.

I can save a lot of time by combining these loading steps on a progressive loader. Using my Dillon press for priming, powder charging, and bullet seating, my rate for these final steps is about 240 per hour.

But because cases need degreasing, trimming to length, deburring, and possibly primer crimp removal, attempting the entire process straight through on a Dillon is not feasible.

SAVING TIME, BIG TIME

Knowing that readers are still saying to themselves, “Did he really say 17 hours? No way,” I have good news.

From the above, it is clear that case prep is the big time sponge in this process. There are places offering once-fired fully prepped brass: resized, trimmed, deburred, primer pockets swaged, and tumbled—all ready for those last three steps. I bought some from three different sources at an average of $150 per 1,000, boosting my outlay per 1,000 from $335 to $500-ish.

Still a huge savings, but the big thing is the approximately 12 hours of case prep time saved. $150 versus 12 hours of tedium? Two words: “Worth it.”

The path to gratification was so shortened that I doubt I will be processing my own brass much in the future.

I wanted to come up with a load that was far enough below “absolute max, danger zone” that I could enjoy the convenience of using mixed cases. Different brands of brass have different internal volumes and exert varying neck tension on the bullet, affecting pressure, velocity, and accuracy. I’d had good results with mixed brass for years, but I wanted to approach it more scientifically this time.

OPTIMAL CHARGE WEIGHT

Where previously I would try different powder charge weights and settle on the tightest-grouping one, this time I used handloading consultant Dan Newberry’s “Optimal Charge Weight” (OCW) method to find the best powder charge.

Briefly, one picks a powder charge weight and makes five variants of it in 1% (I used .2 grains) increments. Fire groups with each load. The load selected is not necessarily the one showing the tightest group, but the middle group of the three having the most similar point of impact. This is the load that will best tolerate small variances such as case volume or powder charge weight without significantly degrading accuracy. As a bonus, cold-bore shots will stay closer to group center with such a load.

My new top-end for testing consisted of a Double Star upper receiver with their Dragon free-float forend and a unique bipod from Vltor featuring individual legs that clamp onto side rails.

Wanting glass that would help me look good on the target, I used a Trijicon Accupoint 5-20X. Wilson Combat of 1911 fame is now making their own rifle barrels, and I used their heavy stainless 20-inch 1:8 twist Super Sniper barrel.

For a trigger group, my old Magpul-stocked Sabre Defence lower got a Wisconsin Trigger Company two-stage. This target-only trigger is a reincarnation of the Milazzo-Krieger trigger that has been a mainstay of top AR-15 target shooters for decades. It is as good as ever and now finally easier to obtain.

PUTTING HANDLOADS TO THE TEST

I baselined this barrel with some known tight-grouping factory ammo and from the very first shots, I knew I had a “hummer.” It made my handloads look good at the sub-1-MOA goal and I got my first-ever, honest-to-gosh, one-ragged-hole group with 69-grain Nosler Match Grade ammo.

On a lark, I fired two factory loads that are not offered as match ammo, but both surprised me with decent groups. The zinc-cored, 52-grain Barnes RangeAR is meant as economical training or 3-gun competition ammo. The Sinterfire 45-grain load’s bullet is pressed powdered copper intended for safe close-range training on steel, where the bullet disintegrates into dust on impact.

Both closely mimicked the 77-grainer’s POI at 100 yards and grouped at an inch or just under.

My reloading results were entirely satisfactory-plus.

SUMMARY

My handloads aren’t setting any records: expensive factory ammo shoots tighter groups. But in dozens of groups fired, I have yet to exceed 1¼ inches at 100 yards even for ten-shot groups, and got down to 1.3 MOA at 500 yards.

I saved significant money and passed some pleasant evenings running the ammo faucet. It makes one a little bit more independent, and even mediocre results are instructive. Good results are instructive and rewarding.

SOURCES

BARNES BULLETS

(800) 574-9200

www.barnesbullets.com

BLACK HILLS AMMUNITION

(605) 348-5150

www.black-hills.com

CORBON

(800) 626-7266

www.corbon.com

DOUBLESTAR CORP.

(859) 745-1757

www.star15.com

FEDERAL PREMIUM AMMUNITION

(800) 379-1732

www.federalpremium.com

NOSLER

(800) 285-3701

www.nosler.com

TRIJICON, INC.

(800) 338-0563

www.trijicon.com

VLTOR WEAPON SYSTEMS

(520) 408-1944

www.vltor.com

WILSON COMBAT

(800) 955-4856

www.wilsoncombat.com

WISCONSIN TRIGGER CO.

(920) 253-1516

www.wisconsintrigger.com