When conducting direct-action missions to take down buildings or compounds, the norm is to expect a close-quarters combat (CQB) fight. This makes the typical choice a shorty carbine with some sort of red dot optic. The reasoning is a short weapon length is best for use in confined spaces and a red dot or holographic optics are very fast for up-close work.

But just because one is operating in an urban environment does not mean the enemy intends to also fight close-up, in which case this exact same set-up could turn out to be totally insufficient to deal with the threat. This is what Special Operations members have learned through years of hard fighting overseas. Basing carbine/rifle set-up on mission versus enemy tactics and actions can prove a costly mistake.

Table of Contents

LESSONS FROM THE WARFIGHTERS

Experienced military members know that, although the mission might be to go in and take down a building full of bad guys, often the fighting is not limited to inside the target structure. They can find themselves fighting their way to the target, on target, and then coming off target. Even in urban areas that could mean having to take shots at threats hundreds of meters away from rooftops, windows, and surrounding buildings.

This was exactly what some members noted in after-action reports from Somalia during the 1993 battle in Mogadishu (made famous by the movie Black Hawk Down). Two factors hampered assaulters’ ability to engage threats from rooftops and across streets at other buildings: first, lack of heavier weapon systems such as more squad automatic weapons and grenade launchers, and second, carbines set up for short-distance shooting, with zeros set for room distance, not long range.

Military members who have fought in Iraq—especially in places like Fallujah and Sadr City—have experienced the same thing. Operators would be in continuous firefights throughout whatever mission they were conducting. It is even worse in Afghanistan, because the enemy prefers to fight at distance. Even in villages they will often fire from wood lines and hills overlooking the village, making the average distance one must be able to shoot 300 to 500 meters.

So regardless of the mission — CQB, reconnaissance, or a simple meet with village elders — carbines must be set up to handle the typical distance the enemy fights at, not for the type of mission itself. Setting up a carbine just for CQB because that is the mission does not make much sense if the enemy refuses to fight close in. The opposite applies to using a “recce” set-up with only a long-range scope because it’s a recon mission, then being forced to face enemy at close quarters.

THE SOLUTION: DUAL OPTICS

This is exactly why the military started issuing Trijicon ACOGs with piggybacked Docter sights around 2005 and later in 2007. Special Operations adopted the Elcan Spectre DR dual-power optic (SU-230) with piggybacked Docter mini red dot sight to give soldiers the greatest capability for shooting at both near and far targets.

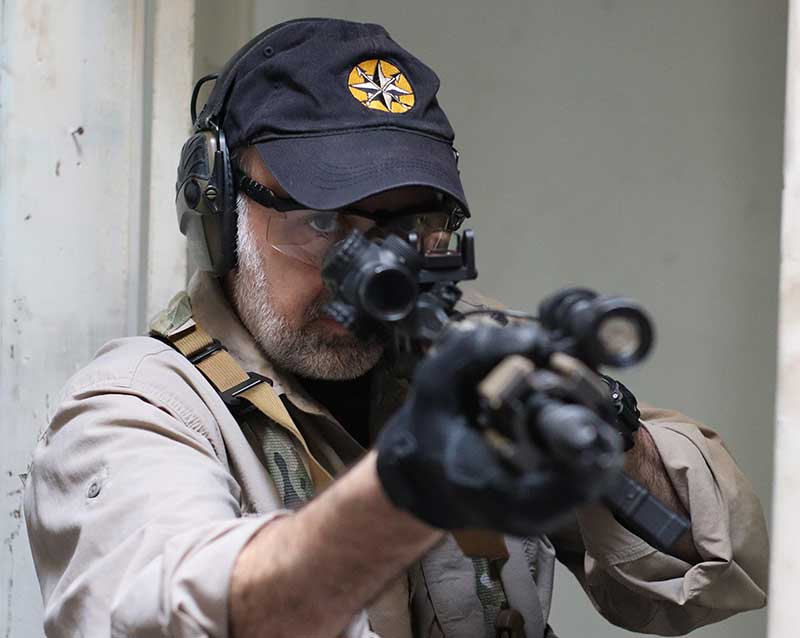

Looking at set-ups Special Forces (SF) soldiers are currently employing in Afghanistan, many are opting for a carbine that has two optics: an offset red dot for CQB and some sort of Low Power Variable Optic (LPVO) for the extended ranges the enemy likes to shoot from.

Of course, one can make do with a single optic. It is totally feasible to take long-range shots past 300 meters with just a red dot and, because modern LPVOs have almost true one-power settings and are very fast up close, why burden a carbine with the weight and bulk of two optics?

The reason is simple. Sure, you can train with a single optic and get good at it, but dual optics give you the best of both worlds almost instantly. I say “almost instantly” because speed is a key attribute. It’s possible to run a single LPVO you can adjust from one power to four, six, or even eight power for long-range shots, but to do so requires you to take one hand off the rifle to adjust the magnification. The same holds true for employing a flip-up magnifier behind a red dot.

That’s time lost one may not have based on the enemy situation, e.g. in an urban area shooting at threats maybe both in the next room and out a window at a rooftop one is being shot at from. One can make do with an LPVO set on one or six power and shoot at both distances, but why “make do” when technology provides a better way?

Using modern 45-degree offset mounts, transitioning between an LPVO and a mini red dot is extremely fast — faster than using a piggyback mounted back-up optic, since there is nowhere near the height above bore distance one has to take into account with top-mounted mini red dots. Plus the shooter does not have to lift their head up off the stock to get a good sight picture, as is the case with a piggybacked optic.

With a 45-degree offset dot, one simply turns the rifle slightly inward while maintaining cheek-to-stock contact to pick up the mini red dot, making for a fast and stable transition between the primary and off-set optics.

In fact, during my last tour in Afghanistan, my Trijicon VCOG stayed on six power the entire time, whether I was inside a building or out in a village. When I did need to shoot up close, I utilized the offset EOTech mini red dot mount on my carbine.

EXCEPTIONS

Of course there are still times when a single-optic gun—especially short-barreled rifles for CQB—is the right tool for the job. Unlike the military, police SWAT teams are rarely in situations where they have to do a lot of shooting at extended ranges.

Take my local police department. The usual crime they face where shots could be exchanged is serving a warrant on a single home. The chances of them needing to fight their way to and from an objective are slim to none. So the selection of short HK416s with Aimpoint T1s makes perfect sense for the situation and what they encounter on a regular basis.

Another way to decide how a carbine/rifle should be selected and configured is by looking at the percentage of the different ranges one encounters in an area. If 75% of engagements take place at a certain range (either near or far), setting up a carbine based on that most likely range is a good idea. But the closer the percentage is to 50/50, the smart thing to do is outfit the carbine to handle all distances (i.e., dual optics).

Additionally, if you are going into an area or situation where the threats’ typical actions are unknown, it’s best to set-up rifles to handle any situation. Once you see a pattern in enemy actions, you can trim down later to a specific rifle set-up.

Aside from a little extra weight, going in with a heavier dual-optic carbine that facilitates shooting at all ranges is not going to hurt you. It’s a lot better than going in ready for CQB and finding out the hard way that no matter how fast your team flows, the enemy prefers to keep a few buildings’ separation between them and you. That makes it necessary to engage them at ranges much farther than you expected and are ready for.

Jeff Gurwitch is a retired Special Forces Soldier who served 26 years in the United States Army (18 years with Special Forces). He served in the First Gulf War, three tours OIF, and three tours OEF. He is an avid competitive shooter in USPSA, IDPA and 3-Gun matches.