As far as Madison Avenue is concerned, the retro trend may have started when Chrysler Motors introduced their successful PT Cruiser—a modern manifestation of the 1940s Plymouth coupe—followed by General Motors with their Chevrolet HHR.

However, there has always been a strong interest in historic and period firearms, whether original or reproductions. The international gun industry, with the encouragement of a relatively new shooting phenomenon, the Single Action Shooting Society’s (SASS) Wild Bunch Action Shooting, has returned to yesteryear with the resurrection of the 1900s’ era 1911 pistol in traditional military dress.

Remington Arms is the latest factory firearms entity to catch the retro bus and, with the exception of Colt, has claim to more 1911 pedigree than any of the others currently involved in its rebirth. More significantly, however, it was the old warhorse’s 100th anniversary in 2011, and you will continue to see a number of companies offering faithful or semi-faithful renditions of this classic weapons icon.

Table of Contents

SASS 1911 CLASSIFICATIONS

The SASS has two 1911 classifications. With your Remington R1 (Remington One) single stack, you can participate in “Traditional” as opposed to “Modern” if you black out the three dot sights. The latter classification permits 1911s of the “Limited 10” genre, but without enlarged magazine wells and they can be shot with both hands. Traditional 1911 events require you to fire one-handed.

REMINGTON RAND’S CONTRIBUTION

During World War I, the U.S. War Department required millions of pistols for its soldiers. It was impossible for Colt to satisfy military requirements, so several U.S. and two Canadian firms were enlisted for the task. Some were not firearms manufacturers, but among the gun companies involved, Remington–UMC delivered almost 22,000 1911s. Production ceased in 1919. Finish was “rust blue” and frames were clothed with checkered walnut stocks.

When World War II broke out, Remington Arms was not called upon to build more pistols, because their main mission now was to produce ammunition for the war effort. However, Remington Rand—of typewriter, not small arms, fame—received an order in 1942 for 125,000 1911A1 handguns. These pistols were not only considered without peer, but they were also the lowest-priced pistols being manufactured for the war.

By the end of the war, Remington Rand had churned out 875,000 1911A1s, which was more by far than any other company involved in the gun’s production.

I carried a USMC-issued Colt 1911A1 in Vietnam, but today, I am fortunate to have a 1943 Remington Rand, Syracuse, NY A1 in my possession. It has one of the smoothest 3.5-pound triggers on a non-competition military piece that I have ever encountered. The lighter trigger indicates to me that someone outside the factory worked on the trigger when it was issued.

REMINGTON R1

Leap ahead 65 years and Remington has joined several other firearms manufacturers in reproducing the GI/ Milspec 1911 and 1911A1. Some manufacturers were motivated by nostalgic demand from patrons, while others just wanted to offer a lower priced pistol, as some 1911s have easily eclipsed $1,000 in the current market. Some versions are exact copies of “Old Slab Sides,” but others have been tweaked with a few more modern touches.

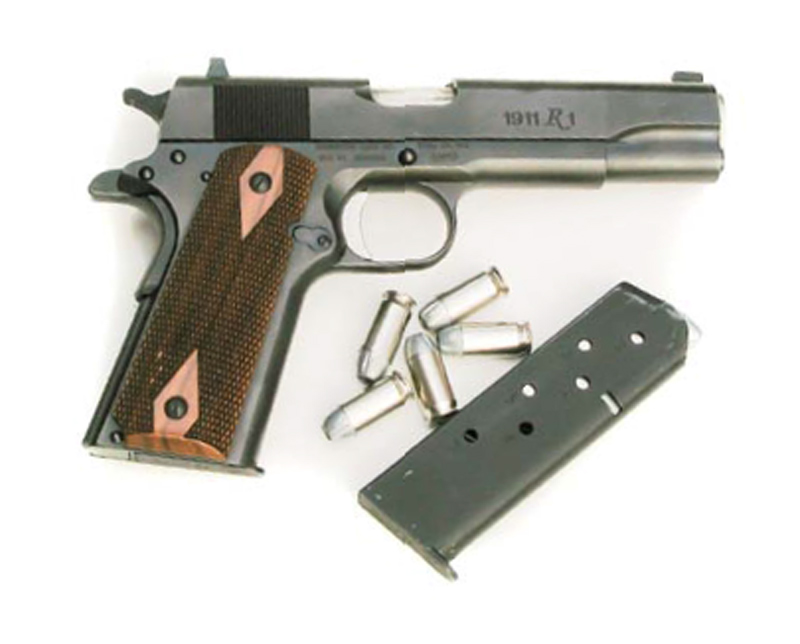

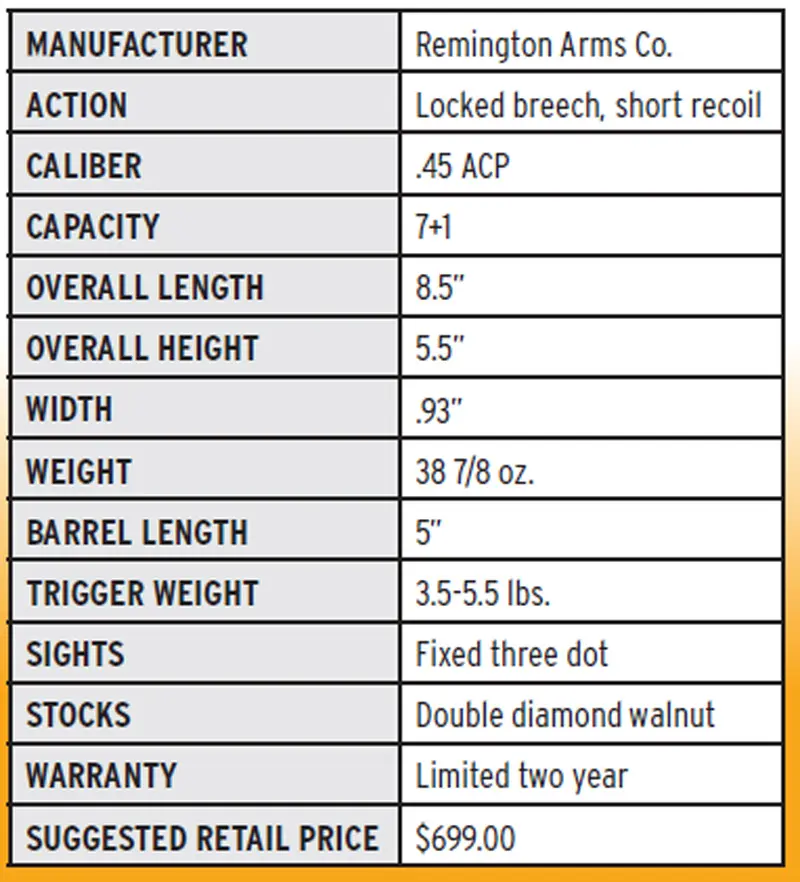

The Remington R1 has lowered and flared the ejection port for enhanced functioning, raised the profile of the dovetailed fixed sights and added white dots for faster acquisition, beveled the magazine well, added a stainless steel barrel link, polished and throated its chamber, and included a Series 80 firing pin safety. Packaged, it comes in a colorful unpadded, lockable plastic case with two seven-round magazines, a bushing wrench, manual and safety cable padlock.

NEW BREED VERSUS OLD BREED

Fully aware of the pistol’s distinguished past and though I knew that Remington intended the R1 to be a shooter, I was nevertheless tempted to treat it as a commemorative piece. However, since S.W.A.T. tends to reject articles that just discuss how great a pistol looks, I decided not only to shoot it, but also to compare the New Breed’s capabilities with those of the Old Breed.

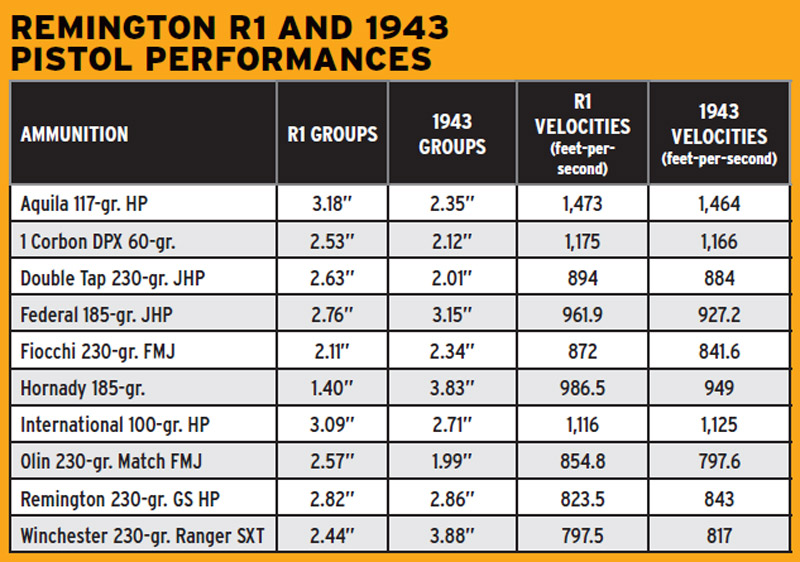

For the test, I selected ten different brands of ammunition ranging in weight from 100 to 230 grains, and shot the two guns side by side. While the 1943 pistol had a lighter trigger, the R1 had better sights and a much tighter lockup. The Old Breed 1911A1 could be disassembled without tools, but the New Breed R1 required the supplied bushing wrench to rotate the snug barrel bushing. The new Remington also had a stainless steel match barrel with a slot cut into its dorsal surface that acts as a loaded chamber indicator.

I like thin front sights on my pistols, but tritium inserts and colored dots usually preclude that. The R1’s dotted blade was .13 inch, which is a nice balance between fast acquisition and precision. Pistol 43’s token appendage was only

.08 inch and sometimes it got lost in the target’s black at 25 yards. Sights on the Old Breed sidearm were useful only if one had the time and coolness to pick off his target—otherwise it was set up for fast point shooting in chaotic close-range confrontations.

Both breeds turned out to be decent shooters. With Pistol 43, I am convinced I would still be wearing the USMC expert medal after requalification. Although the R1 shot low left and I had to use Kentucky windage to center my shots, average 100-round group size from a handheld rest at about 25 yards for both sidearms was 2.67 inches, with the R1 having a slight edge. There was only one stoppage, and that was with the R1 and Federal’s 185-grain JHP. Its exposed, cavernous cavity’s lead lip got hung up on the feed ramp, but cycled through on the second try.

Although it was a chilly 40 degrees, top velocities of 1,492 and 1,479 feet-persecond (fps) were garnered by Aquila’s IQ 117-grain zinc hollow point bullet in the R1 and Pistol 43 respectively. An urban myth has grown up around this bullet’s body armor penetrating capabilities, and some time ago a NOTAP (Notice To All Police) had been communicated to departments concerning this. Subsequently, I fired three .45 ACP IQ rounds into Level II armor at five feet. All three failed to defeat the vest.

On average, velocities were higher in the R1 1911. Perhaps the fresh R1 barrel had a better seal and more propellant was confined to propel the projectile? The tightest five-shot R1 group of 1.40 inches at 25 yards was obtained with Hornady 180-grain Critical Defense ammo. Pistol 43 delivered a 1.99-inch cluster with very dated Olin 230-grain Match at the same distance. The R1 is definitely a shooter, albeit a nostalgic one and, although both pistols engaged in some dominant-hand hammer bite and frame gouge, the New Breed would certainly serve its owner well defensively or as a competitive piece in SASS shooting venues.

The seven-round R1 magazines have polished followers and numbered cartridge holes. They are as sturdy as their antecedents and also fit and work in Pistol 43. The magazine base cannot be removed, and magazines must be disassembled from the top for maintenance.

TYPICAL 1911 HANDLING

Recoil is what it always is with the big bore bullet launcher, but not uncontrollable. Without checkering, one must apply a little more muscle to make the gun behave, or it will get away from you and you’ll lose precious time regripping it between shots. Unless you’re a neophyte, front strap checkering or the application of skateboard tape will solve most problems associated with recoil and pistol torque. The R1’s mediumlength trigger is typical military, with a modicum of slack before the brakes take hold. With continuous pressure, it breaks cleanly. Reset is short and quick.

R1 FIELD STRIPPING

Field stripping is traditional 1911, but as mentioned earlier, the bushing is tight and needs a wrench to rotate out of battery to release the recoil spring plug and recoil spring. The plug is under considerable tension and can become a formidable missile if control over it is lost. A long time ago, I broke my raised camper shell rear window when one of these went flying. Therefore it’s wise to wear shooting glasses when tinkering with this type of handgun.

Move the slide rearward until it lines up with the disassembly notch, and push out the slide stop. Ease the slide off the frame. Pull up slightly on the recoil spring guide, and remove it and the recoil spring from the slide. Turn the bushing counterclockwise and remove it from the slide. With the barrel link down, slide the barrel out of the slide. Reassemble in reverse order.

CONCLUSIONS

With several updates, the R1 is a semi-faithful reproduction of Remington’s worthy contribution to the Big War effort. The similarities in accuracy and velocities between the R1 and Pistol 43 would indicate that Remington has faithfully copied the original blueprints as much as contemporary liability issues and the quest for reliability with modern higher pressured ammunition allowed them to.

The spur hammer and grip safety will bite some hands, and I appreciate the more contemporary Colt Commander- style hammers and beavertail grip safeties that eliminate this irritant. For some customers, shooting gloves will be a must unless further modifications are made.

Fit and finish are very good, both outside and inside, and the addition of premium stocks and components make the R1 a very desirable pistol. A stainless version will be offered in mid-2011.