Red dot sights are a tremendous aid in getting fast hits. They’re gaining in popularity and credibility with each passing week, as more are successfully used in both combat and serious training. Use of the sights has allowed trainers to embrace techniques that take advantage of their unlimited eye relief and single sighting plane.

In the April 2008 issue of S.W.A.T., Pat Rogers provided an outstanding survey of back-up sighting options for use should a red dot sight fail (RED DOT DOWN! What To Do When Red Dot Sight Fails). I have trained to the various contingency actions should an optic no longer have the dot when needed and had some opinions. However, the arrival of a new optic for my carbine provided an excuse to go out and seek hard numbers for the different scenarios.

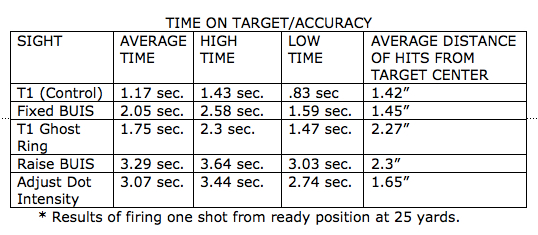

Running different contingency actions for optic failure against time and accuracy provided hard data to compare appropriate employment considerations. Each method produced capable hits within common engagement distances.

Table of Contents

THE PARAMETERS

A word of caution: These results reflect one roguishly handsome correspondent firing a specific carbine at a shade past 25 yards using an Aimpoint T1 on a LaRue tall mount. The data can suggest some points for your consideration, but may not translate to your exact predicted outcome. Look at my results for some ideas and go verify using your rig.

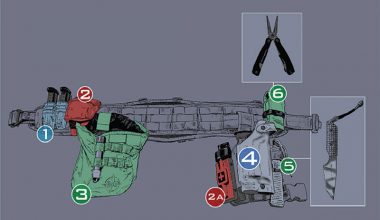

As mentioned, the optic in use was the T1, in this case with the Noveske spec’d Troy BUIS fore and aft on the mid-length N4 Light Recce. This version of the Troy rear presents the rear sight with the large aperture up. For the test the front remained up throughout.

The drill was shot in each case from the ready, carbine pointed to the ground at the target stand base and presented to the chest circle of Warren Tactical training targets upon the signal from a PACT Pro Timer.

Raising rear iron proved slow and may be better employed as a continuing action once immediate threat is down.

The rifle would be presented to target as normal, the dot looked for and, not being visible, a contingency action would be conducted. One shot was fired as quickly as the contingency action could be completed and the sighting method acquired, seeking only enough accuracy to place the shot inside the target’s seven-inch circle at roughly 25 yards. Time was recorded and the same cycle repeated. Twenty-five yards was chosen to demand a level of precision in sight alignment, represent a distance where transitioning to a secondary weapon is less viable, and still be within the most common engagement ranges of military and LE use.

WHAT HAPPENED

I first fired a control sample with the T1. The average time to shot was 1.17 seconds, with the fastest being .83 second and the slowest 1.43 seconds. All shots were tightly clustered no more than 1.42 inches from the target center. I then dialed the T1 down until the dot was no longer visible, and raised the Troy rear. Dropping my head to pick up a lower third co-witness was simple, but slower than I had expected. The distance required me to look for the dot, react, pick up the rear aperture and then refine the sight picture, for an average time of 2.05 sec., or .88 sec. additional from the control time to fire with the T1 on. Hits were good, with only a marginal increase from the control, with all shots no more than 1.45 inch from center in a nice round group.

Co-witnessing was looking good, even though I have never trained with the distraction a fixed BUIS causes me. Twenty years of using iron sights in various operational and competitive arenas have programmed me to look through the aperture, and it is a constant lure to avoid when one is up in the lower third of the field of view.

Next up was the optic ghost ring method. The technique was surprisingly fast, since I did not have to lower my head any farther, only to reference the front sight through the tube once the dot wasn’t there. Average speed was 1.75 seconds: .58 sec. slower than the control but .30 sec. faster than the lower third co-witness. Hits were good, and not surprisingly, most of the deviation was vertical. The average distance of all hits to target center was 2.28 inches.

Two points are worth noting here. One, the front sight tower was not marked with a reference line to hold elevation at the base of the Aimpoint’s tube. This technique would likely have tightened the group by some degree.

Second, my mount and cheek weld were very consistent. Shooters who struggle in those areas will see a much greater dispersion of hits with this technique.

Looking at the chart shows that physically raising the back-up iron sight was slow, requiring 3.29 seconds to accomplish and get the hits. It is worth pointing out that this test is perhaps the least relevant as a universal example to other users, since there are so many BUIS options out there, each with slightly different ways of activation.

I found that the Noveske/Troy was very simple to raise, even though the test was conducted wearing gloves. My left thumb went straight to the locking pin as my fingers curled around and dragged the tower up by the aperture’s protective wings. Another sight may have been faster or slower—caveat emptor.

On one shot, I fumbled the raise, and the sight was about 7/8th of the way up when I fired. The impact was the lowest of the group, but the recoil settled the sight into its pocket and locked it into place. The hits averaged 2.3 inches from center. The increase from the co-witness results were explicable by my rush to reacquire the support hand on the vertical foregrip and break the shot in order to compensate for the down time raising the aperture.

It occurred to me that to thoroughly test the contingency actions against time and accuracy in order to make conclusions about capabilities, I also needed to test how long it would take to simply present to target with the intensity of the dot turned down, adjust the intensity and break the shot. The current generation of optics is magnificently reliable, and there are multiple scenarios where if a user presents and doesn’t get a dot, it is because of operator error.

For example, those who have early generation optics or developed habits from them often turn the sights off to conserve battery life (some optic brands do this for you, leaving you in the same fix). Care to guess what condition the optic will probably be in when needed?

Even for those who leave the optic on, a great number of fights occur in transition periods such as the proverbial attack at dawn. If the optic was adjusted for darkness/indoors or night vision use, and the fight goes into daylight, there is a very good chance that the user won’t recognize the need to turn up the power until the rifle is on his shoulder and the dot isn’t there. Adjusting the intensity is not recommended as an immediate action, but rather as a contingency when the rifleman knows he turned the power down or off.

The large intensity ring on the side of the T1 was easy to grasp and shove about ¼ turn forward with the shooting hand, resulting in plenty of dot and predictable hits. Even with removing the firing hand to accomplish the task (attempting to turn the ring with the support hand was clumsy, slow [over five seconds] and difficult to turn), the results were about a quarter-second faster and hits 39% closer to the center on average than raising the rear sight. Here again, the make of a shooter’s equipment may influence results. My anecdotal experience with other optics would lead me to expect that the M2/M3 and M4/M4s Aimpoints may produce similar times, while the EOTechs would likely see longer times as one attempted to manipulate the small button and get back on the grip.

Reference line may help in using ghost ring method. Strip of tape helps to establish correct elevation until live-fire validation allows shooter to paint more permanent line on.

Finally, after seeing the results of the ghost ring method, I decided to push the envelope. I moved the target out to 100 yards and flopped into prone. Shooting rapid fire cadence from a magazine monopod, I fired a control group into the head of the target, turned the dot off, reloaded, and fired ten into the body using the T1 as a really large aperture. The control group measured three inches, all within 2.5 inches of the aiming point.

The ghost ring yielded five hits out of ten into the vitals-only training target, with the remaining five shots within eight inches of the target’s center. Later refinement of the exact needed sight “alignment” and using a reference line on the front sight tower allowed better hits, ultimately allowing me to pick clay birds off of the 100-yard berm. However, the first test is likely more representative of an immediate action at that distance.

In some specific circumstances, best answer may be to simply increase intensity of dot, as this was consistently faster and more accurate than raising BUIS.

SO WHAT?

I learned some things. For me:

- The optic as ghost ring is a viable fight winner inside of most close-in fights. I can still get hits on full value targets out to 100 yards with certainty, and vital hits at least half of the time. It will be my immediate action response to dot loss.

- The increase in accuracy with a co-witness is not worth the extra time relative to the ghost ring and the distraction it causes me. One-third of a second is insignificant in most aspects of life, but that time could very well mean three more rounds my way at Kalashnikov cyclic rate or an irhabi that is one running step closer to cover or a crowd.

- The difference between raising the rear sight and just running the front sight through the tube averaged out to 1.54 seconds. That is a long time in the thick of things, equating to a near threat reacting to your location and presenting a rifle for an aimed shot, a long burst, or 15 feet of closure for a sprinting, machete-wielding maniac. Raising the BUIS will be my continuing action once the immediate threat is serviced.

- If I know the dot is gone because I turned it down, I would rather crank it up than raise the rear iron for a tight or long shot. If my luck is really gooned up and the battery is dead, I can still run straight to ghost ring and the data here would suggest a hit at about 3.65 sec., or within .01 sec. of the slowest shots when raising the BUIS. Again, this is a contingency action under a specific set of circumstances and not an immediate action.

Actually running the methods against the timer gave me a much better idea of their place in my personal toolbox. I highly recommend running your gear through a similar comparison. Hard results yield much better TTPs than firm opinions.