You just went out and bought a new gun. You did your due diligence, read the reviews, and talked to your friends who own this make and model, or other guns by the manufacturer. Perhaps you even had a chance to fire someone else’s gun before you decided to buy.

Along with the gun, you bought some new ammo, and both the gun and ammo come from well-known and respected makers. You expect the gun and the ammo to be “perfect.” What are the odds they will be?

Table of Contents

QUALITY CONTROL

Everything that is manufactured should be subject to Quality Control (QC). But one of the facts of life is that it is economically unfeasible to measure every part of every gun. It could be done, but your basic 9mm semi-auto could cost $10,000 to pay for all the tools and people to measure every single individual part of every gun a big company makes.

Every trigger, striker, pin, and spring would need to be measured and tested. Worse yet, some parts can only be tested by destroying them. So a 100% sample means after the testing, there are no parts left to go into the gun.

QC is based on testing samples—the larger the sample, the greater confidence you can have that all the others measure up. So how big a sample? Statisticians (folks who actually like to crunch numbers) constantly try to figure out how small a sample is representative, which they call the “degree of confidence.”

We see this in elections, when a poll is taken in advance of the election to predict who will win. But polling, like testing, costs money, so we see “nationwide” polls where they sample 1,000 people or less and predict a winner. The last Presidential election showed how imperfect this system is.

It may be easier to get your head around this by considering ammunition. One round of ammo has only four parts: case, primer, powder, and bullet, or six if you count the parts in the primer: cup, compound, and anvil. If you want to be 100% sure a primer will fire, the only way to do that is to fire it!

TEST FIRING

If you buy a 20-round box of your chosen personal-protection ammo from a reputable company, you should—make that must—fire some of the ammo to make sure 1) It will work in your gun, and 2) You got a “good” box. Consider that if you make one million of anything—including ammo—and you have a 0.01 “error rate,” that is still a lot of bad ammo getting sold. This is why you need to practice malfunction drills—in case you got the only bad round your chosen maker ever let out.

If I were a rich man, I would shoot nothing but personal-protection ammo for practice and competition. Well, I’m not, nor do ammo makers ship me pallets of ammo to try. I go into a gun shop and buy it the same way you do, 20 rounds of 9mm personal-protection ammo, at something over a buck a round.

HOW MANY DO YOU FIRE?

I cheat and buy two boxes at a time, from the same lot. I tend to shoot five rounds selected at random from each box as a test sample. If all ten function 100% in my gun, I feel confident all the rest will work too.

I have had the opportunity to tour several ammo makers, and the last step in those plants, both large and small, after gauging and in some places a computer-controlled laser measurement, is a visual inspection by hand of every round.

The inspectors are usually female, as they have a better “touch” and focus on this repetitive job. Their supervisors sometimes have trouble detecting the tiny flaws they rejected, but the inspectors can point them out!

But no matter how well trained and experienced those inspectors are, a bad round can still sneak through. After all, those inspectors are people, and people make errors.

Over the years, QC has gotten much, much better. Over my last 49 years as a firearms instructor, I have handled lots of factory-fresh ammo. During my nine years at my agency’s academy, I trained over 5,000 students, and every shot fired was factory-fresh, JHP personal-protection ammunition.

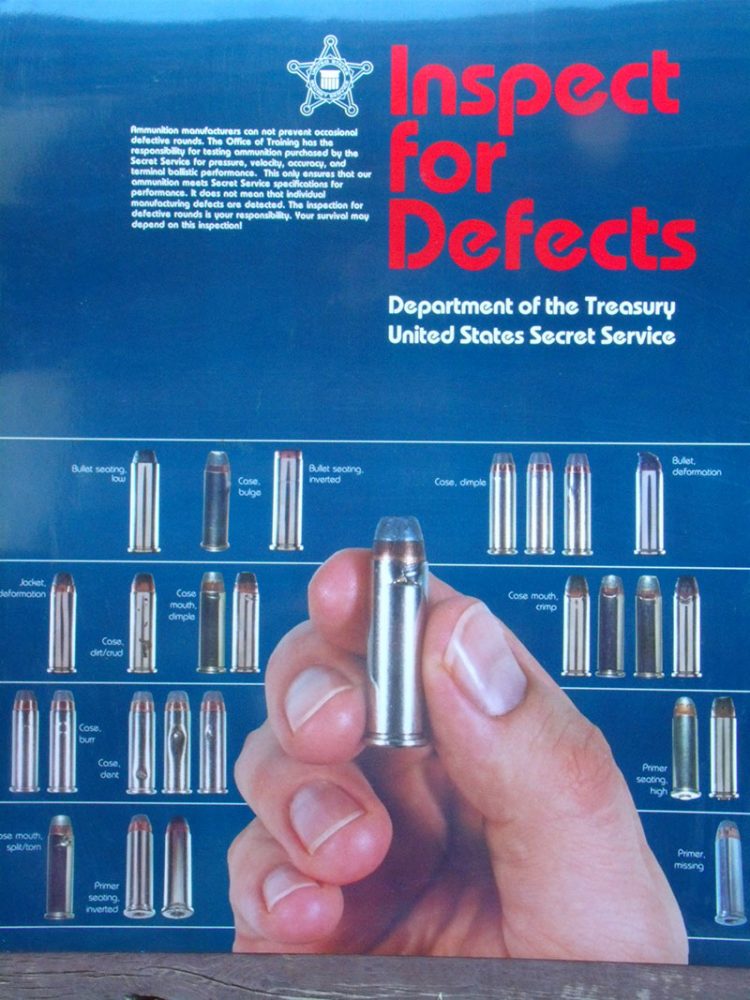

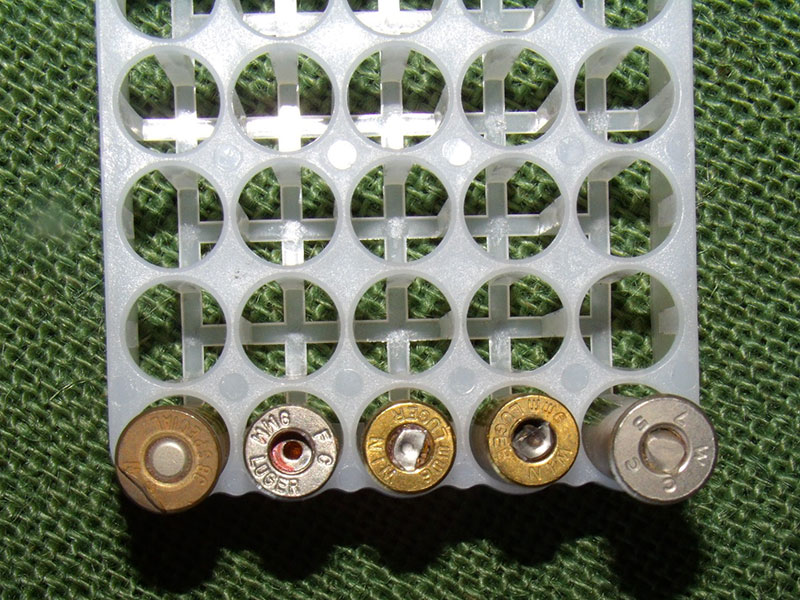

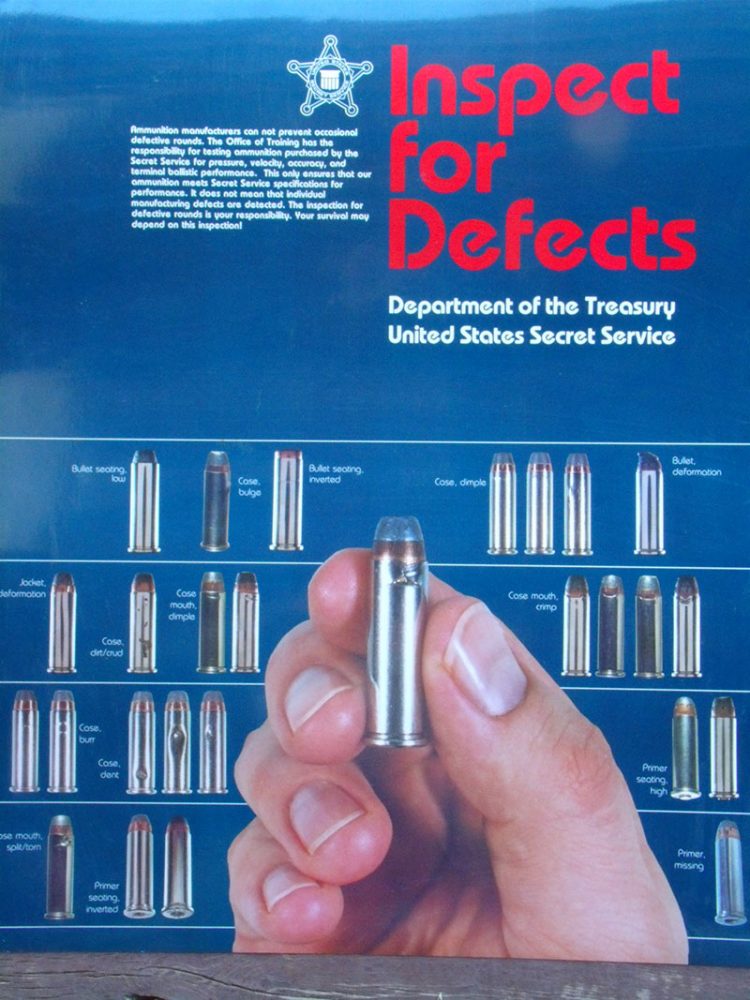

As the accompanying photos show, we got a fair amount of bad ammo. (The rounds pictured only came from certain manufacturers, but all ammo makers would have the same defects in about the same percentages.) Defects included no primer, primer in reversed, no primer and no flash hole, bullets in backward, some kind of pin inside the case, and so on.

It was so bad that the U.S. Secret Service issued a poster titled “Inspect for Defects,” picturing some of the bad ammo they had received. My absolute favorite I found when I was in a field office. I was issuing 12-gauge slugs and found the last round in the box: case, primer, powder charge, wad, roll crimp … but no slug!

FIREARMS QC PROBLEMS

Gun makers have QC problems as well, including even the big companies with great reputations. How far off can they be? At our academy, I issued the service guns to our new hires. At the time, we used a double-stack 9mm pistol from a major maker with a sterling reputation. I opened every box, never relying on the end sticker for the serial number.

I received several guns that were still loaded from being test fired! In one case, I found not our 9mm, but a two-inch .38 Special revolver! The box said it was our 9mm model, but someone had slipped up.

Consider all the parts in your new pistol. Each one is made with some tolerance in the specifications—it should measure X, plus or minus Y. One issue for the engineers is called “tolerance stack.”

Let’s say you get a striker at the high end of the acceptable limit, and the hole in the slide is at the low end of its tolerance. Now the striker can’t reach the primer. Or worse, it sticks forward, and the gun slam fires out of battery. Or a pistol is made where the parts in the trigger-to-striker links are all on the small end. Then you may have a pistol where you can pull the trigger all you want, but the striker never falls.

A local dealer related that he obtained three revolvers from another big American firm. The triggers were great and the actions smooth—when dry fired. But when customers loaded the guns, the cylinders would not revolve. Seems they had made the space from the frame to the back of the cylinder so small that there was no room for the case rims.

These examples explain the large number of bald engineers, as they have pulled their hair out trying to find the perfect tolerances for every part.

Once again, the human element enters the equation. A friend ordered a high-end bolt rifle from a prestigious maker. It arrived, and after he mounted his scope, he went to move the rifle to his vault, only to feel the barrel twist in his hand! The barrel had been screwed into the action but not torqued tight.

Another gent bought a quality 1911 in 9mm and tried several magazines in it before bringing it to the range. Once there, his magazines kept falling out of the gun. The magazine catch was stuck, half way out and unable to lock the mag in. The magazine release screw was not a flat, Phillips, Torx, or Allen head!

Both guns went back to the makers, who made them right.

Personally, I once bought a .357 Magnum revolver from a major company. No matter how I tried, what ammo I used, or how much I adjusted the sights, the gun fired to the left. I then looked closely at the barrel. The rifling was deeper on one side than the other. I repurposed the gun into a PPC gun with a six-inch bull barrel.

Even a single maker can have times when their QC slips. One maker had new owners who did not see any reason for strict QC—it cost money, and that was all they cared about.

Quality Control is not considered a “profit center” by the bean counters. Instead it’s a place to cut costs. QC dropped, guns came back for repairs, they started losing sales, and they lost part of the market to another company that paid attention to QC.

TESTING OF RAW MATERIALS

This matters too. Some ammo makers buy brass rather than make their own. One company tests every lot of brass before loading it and found a single lot from a reliable maker with the wrong heat treatment, meaning the brass could break in your gun when fired.

Another company that uses polymers in their guns failed to test every lot of raw material. As a result, they have made a number of guns where the frames crack when fired—and they cannot identify which models, let alone which guns! Not something to inspire confidence in their products, even though they have a great service department, and warranty repair (replace) any broken frame.

Ultimately, we have to rely on the reputation of the companies we deal with. There are a few whose guns and/or ammo I will not shoot, even if they are free. There are others whom I trust, even if their past has a few recalls.

I do tend to wait a year or so before rushing out to buy the latest and greatest new thing. Even new designs from trusted firms can have teething problems.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

1. Closely inspect your new gun before you leave the store for any obvious defects.

2. Follow the instructions (yes, every new gun comes with instructions), which usually state you should clean and lubricate your gun before you fire it! It’s a great time to find machining chips in the action, loose parts, or parts rubbing where they should not.

3. On ammo, look at every round of your personal protection ammo for primer, case, and bullet defects before you shoot the first round.

Every maker wants to provide you with perfect guns and ammo, but the employees are human, and humans make mistakes. Do your part by looking at and testing your guns and ammo.