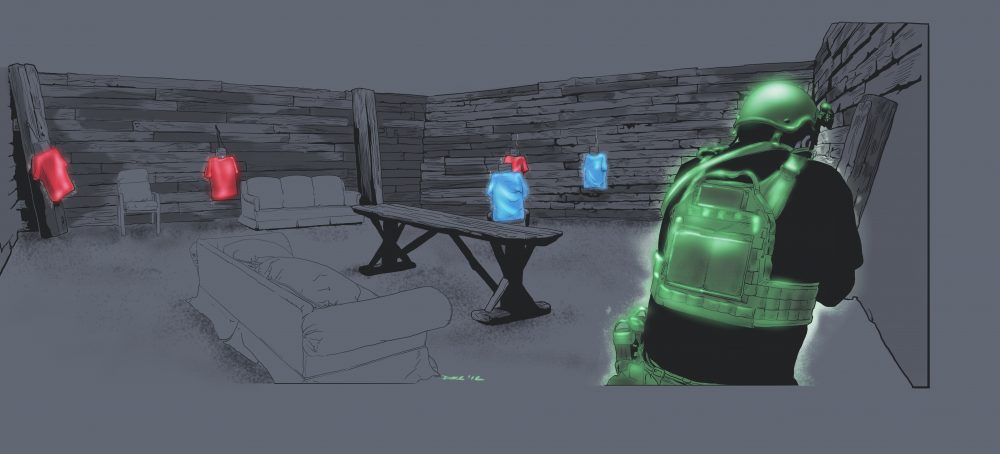

Prioritize your work. Steve Fisher and Paul Buffoni negotiate four-way intersection at Alliance, Ohio PD shoot house. They have already taken out one bad guy (red shirt), but still have a lot to consider. The only way to deal with complex problems is to break them down into smaller parts and deal with them one at a time.

Learning occurs in many ways and at different rates. It is an individual endeavor, and most are able to crack the code once they put their mind to it.

For example, it requires no conscious effort for you to open the door of your automobile. If you hop into your brother-in-law’s car, the door may open in a different manner, but you should be able to figure it out in a few seconds and without the help of a Power Point presentation or a consultation with your smartphone. If you can’t function without the aid of such devices, avoid any activity that involves making decisions on the fly.

Learning to function under pressure—so important to some in this society—is often easier said than done.

At EAG Tactical, we run a number of Shoot House/Combat Life Saver Courses every year. Several negative traits pop up with disturbing regularity among students. We understand clearly that most who carry a gun have limited training in the use of that weapon. And it is a weapon.

Those who proclaim a firearm must have a “sporting purpose” have no clue as to what the Constitution says, nor why we as Americans can possess those weapons. We do not have guns primarily for “hunting” or undefined “sporting purposes.” There are in fact many who do use their weapons for those purposes, but they are secondary reasons only. The framers of the Constitution had a clear understanding of what they were doing.

But I digress. This article concerns what you have to focus on in a fight. In its most simplistic form, that answer would be “the bad guy.” But there are other areas of concern directly related to that bad guy. These include, but are not limited to, areas within which people can enter, exit, hide, and use as cover.

Most humans have the disturbing tendency to try to see everything at once, rather than concentrating on what is important. The result of this all-encompassing endeavor is that the internal circuitry becomes overloaded and some—many—default to zero.

Seated in a chair is a no-shoot, identified in these scenarios by a lime green shirt. A bad guy—identified by a red shirt—was standing behind the no-shoot. The bad guy has been engaged and dropped to the deck. Behind the only other piece of furniture in the room is an unknown target (wearing a blue shirt). It took these two very good cops a few seconds to understand that they had not yet dominated the room. It’s all about angles and situational awareness.

Table of Contents

PROBLEM SOLVING

We state regularly that our shoot house courses are not about shooting, but are exercises in problem solving. For those who go in harm’s way, problem solving can be defined as a mental process to discover, analyze and neutralize threats. An analogy is the Pre-Engagement Sequence, in which we acquire, identify and process a target.

We have to react to the threat. We have to first understand that there is a problem. We then have to make the decision to resolve the problem. This includes understanding what the problem is and the options available to process it. If our understanding of the precise nature of the problem is faulty, our attempts to process it will likely be faulty.

The problem we are facing, and what makes our problem solving different from that of the administrator of a group of office drones, is that we are operating in real time. And like aviators, freefall parachutists, climbers, divers, and others in high-risk jobs or sports, the results of our problem solving can be life changing.

MENTAL PROCESSES

Although I am talking about training, that training is a step toward doing this operationally. There are a number of mental processes at work, which may include the following:

- Perceptually recognizing a problem: What is wrong with this picture?

- Representing the problem in your memory: Have you seen/dealt with this before?

- Considering the relevant information as it applies to your current problem: Prioritizing work.

- Identifying specific aspects of the problem: Additional prioritization of work.

- Labeling and describing the problem: Communication.

Going into the shoot house, you start by recognizing a problem. You have a clearly defined set of circumstances. You are given a scenario that includes physical descriptions of all who are inside, including bad guy targets, unknown targets, and good guy targets.

You are also briefed on which instructor(s) will be in the house with you. You may be shown pictures of the participants, given the applicable rules of engagement and the scope of movement within the house. This is all pretty simple, and initial entries into the house are indeed simple in every way, except that you are doing something that is the opposite of what you have been trained to do on the square range all your life.

On the square range that administrators and managers love so much, someone tells you to load, what the next drill is, how many rounds you need to fire and where. They ask if you’re ready and tell you to shoot. They may even tell you when to reload and when to holster.

Having your equipment issues taken care of is a key to problem solving. Ammunition management is an issue that many gloss over. Member of Pentagon Force Protection Agency executes tactical reload with his issue LWRCI M6A2.

BEHIND THE DOOR

But the shoot house may start when the instructor briefs the scenario, asks you if you have any questions, and says, “The fight starts on the other side of that door.”

And now things change. If people are new to this, no matter what they are taught, there will be much pointing, unnecessary talking, and serious posturing. Eventually they enter a single room, go to their point of domination while engaging a single bad guy each, collapse their sectors of fire, and hopefully start breathing again.

Assuming all goes well, we ratchet it up for successive runs, increasing the complexity on several levels. On the next run, we might add an unknown target. Not a “good guy” and certainly not an “innocent” (where do people get these ideas from?), but someone who is, well, unknown.

Now we are forcing students to think. They have a new problem and have to prioritize their work to handle it efficiently. Unfortunately, this is where people get stuck. Something is different than before—an unknown target—and that requires a different approach.

- Recognize the problem: There is an additional body in the room.

- Have you dealt with this before? Maybe not under these exact circumstances.

- Consider the relevant information: Prioritize the work—is he an immediate threat?

- Identify specific aspects of the problem: Is he armed? Evincing hostile intent? If not, deal with those who are trying to kill you first, then go back and challenge the unknown.

- Label and describe the problem: Unknown person. How do we handle him or her?

PROBLEM-SOLVING TACTICS

It’s simpler if you have a game plan before you go through that door. Here are some problem-solving tactics you can use to help you.

Algorithms

This is a methodical, step-by-step procedure that will always give you a correct solution. The downside is that it is time consuming and therefore not practical for those who FISH (Fight In Someone’s House) for a living.

Heuristics

This is a mental rule-of-thumb procedure that involves trying a number of solutions and discarding those that don’t work. There is no guarantee that anything will work, but it does allow you to simplify complex problems and reduce the number of possible solutions to a more manageable level.

Trial and Error

In our work, it might go something like this. In the day, the shooter would only fire a pair to the body—which was the Standard Response—then lower the gun to assess. If his target was still up, he would slow down and take a brain shot. He’d “tried” the pair and it was a mistake. He shot for the brain and voilà! Another notch on the hero’s belt.

In reality, this entire drill is an error. Above-average police departments are connecting with about 20% of their shots, so they are already behind the power curve.

The “pause” that was bandied about so much is also false, because while you are lowering the gun and assessing, the shots you fired may not have hit, and if they did, they may not have been effective. The presence of the bad guy’s head along your sighting plane will determine if you need to continue shooting.

The true trial and error here is that two pistol rounds will probably always be deficient. We must always be prepared to fire follow-up shots.

Insight

In some cases, the solution may appear as a sudden insight. You may feel that the problem is similar to something you have seen or dealt with in the past. This familiar feeling can lead you rapidly down the proper path.

But the downside is that, if you lucked into the proper solution initially, you may continue to use the improper solution until it causes you to fail. Luck is not a TTP, though many cops seem to think that way. The system is not flawless.

John Mattera enters a room and is faced with a series of problems. He prioritizes his work and engages a bad guy (red shirt) in the hallway at the far end of the room. Once he has successfully prosecuted that threat, he has to break the room down into component parts and isolate other Red Zones so he can determine if other threats exist.

PROBLEMS WITH PROBLEM SOLVING

There are four issues that relate to each other and cause us to function poorly.

Functional Fixedness

This is a tendency to view problems only in their customary manner. It prevents people from seeing all the options that might be available to them.

Irrelevant/Misleading Information

It is necessary to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant information, because the latter can lead to faulty decisions. The more complex the situation, the easier it becomes to focus on the misleading or irrelevant information.

Assumptions

Some will make ASSumptions about constraints and options. This can prevent certain solutions.

Mental Set

Some will only use solutions that have worked in the past instead of looking for an alternative solution. Mental sets can lead to inflexibility.

And how does this relate to us? Most people apparently live in a parallel dimension and are incapable of breaking things down into their component parts.

INABILITY TO SEE OR ACT

One of the more disturbing problems is centered on a shooter’s inability to see the forest for the trees. Or more accurately, the inability to distinguish between what is important and what is superfluous.

At class, I get very proficient square-range shooters who, when entering a room in the shoot house, freeze in the door. Or move to a bare wall and stare at it, doing nothing else. Not going to a point of domination, not collapsing their sector of responsibility. Nothing.

And while this is at the extreme end, a more common problem is that they enter the room and don’t see much of anything.

Some people enter and basically lock up. We attempt to prompt them by asking what they see. Of course we are hoping they will respond correctly and sing out with the red zones—the danger areas—where people may be lying in wait and looking for a tactical advantage.

Sometimes a student breathlessly reports that he sees an end table, white in color, with two drawers and a lamp on top. This is usually accompanied by pointing with his dominant hand, thereby reducing his ability to use the weapon.

Wrong answer. Instead of focusing on something that has the potential to shield a bad guy, students get wrapped around the axle and concentrate on something nebulous. This is an almost textbook example of Functional Fixedness coupled with Irrelevant Information. Nothing he described can hurt him.

Normal average earth people live in an advanced state of Condition White, and are so occupied with their handheld electronic devices they would not realize it if a meteor were about to conk them on the headbone. And when Mr. White enters a room, he sees everything but understands nothing about what he’s looking at.

When a shooter enters a room, he must be able to use his internal filter to judge what is important. He has to see and make judgment calls as to who is armed and a threat, who is not a threat, and where additional threats may be lurking. It is not something that comes naturally—it must be developed. For this exercise, those wearing red shirts are bad guys. Those wearing blue shirts are unknown and have to be handled differently.

BREAKING IT DOWN

When we enter a structure looking for someone, we need to concentrate only on those items and places where that someone may be or be hiding in, under or behind. Clearly someone who is dedicated to hurting us will also be exhibiting certain aggressive cues via stance and movement, and he may also be holding or deploying a weapon. These visual cues should be immediately obvious.

If your visual receptors have not flashed on the bad guy, the very next thing you need to do is look for those places where he may be hiding. In a small room like a bedroom, there are only so many places he can hide: behind or under the bed, in a closet, or behind furniture.

But a larger room such as an office suite may present a series of complex problems relative to both the size of the room and the number of places where the bad guy might be concealing himself.

In that case, you need to take the large room and quickly scan it. If nothing is apparent, break that big room down into a pair of medium rooms, and start scanning again, from close to far. And if that doesn’t work, break that medium-size room into smaller holes where someone who wants to hurt you might be waiting.

It isn’t rocket science. It is common sense—but it has to be immediately applied.

IN DEFENSE OF SHOOT-HOUSE COURSES

Pundits have bemoaned the fact that shoot-house courses are available at all, denigrating them as a cottage industry. Shoot houses have previously been available only to those mil units tasked with CQB (as opposed to MOUT) and some progressive police agencies.

Shoot houses have until recently been unavailable to most cops and almost all civilians. This is unfortunate, as training commonly consists only of square-range work, which allows one to grasp the fundamentals of marksmanship and weapons handling, but little else. The live-fire shoot house introduces a shooter to a three-dimensional environment, movement, and problem solving.

On a square range, all decisions are made for you. You are told which target to shoot, how to shoot it, when to shoot, and when to stop. All you have to do is pay attention and apply the fundamentals. The final step is force-on-force using simulated ammunition.

Everything has its place within the operational context.

I have been in shoot houses—either as a student or instructor—since the mid 1980s. The classes are time and energy consuming, but are rewarding to teach for the simple fact that they are alien to most who own guns. The result is that some switched-on shooters will see things with a clarity they haven’t previously had.

Understand that while the shoot house involves CQB, it does not necessarily mean it is unique to a platoon-sized group fast-roping onto a roof and using explosive breaching to get through doors. It could be two patrol cops clearing a building on an alarm call and finding bad guys present. It could be a pair of businessmen who operate a jewelry store fighting armed robbers who, after all, just wanna get paid. Or it could be a husband and wife team defending their bedroom from one of the most dangerous of criminals, the nighttime burglar.

And while it is all CQB and certain similarities are involved, there is also a chasm separating military direct action from police warrant service, and an even bigger one for the businessman or family defending their castle.

No matter what clothes you are wearing or foe you are engaging, you still have to acquire, identify and prosecute the threat you are facing. You have to sort out what is in front of you, and do it efficiently. You need to visually break a large room down into a medium room, and that room into smaller sections where bad guys may be hiding.

And you have to do it right now…

Pat Rogers is a retired Chief Warrant Officer of Marines and retired NYPD Sergeant. He is the owner of E.A.G. Inc., which provides services to governmental organizations and private citizens. He can be reached at [email protected].