The pistol is really a weapons system that encompasses the carriage platform that gets the weapon to the fight, the “launcher” (handgun), and the missile that does the work. For best effect, all three have to be tailored to the man, the mission, and the environment.

Aside from a few oddball weapons out there, service pistols are operated by the recoil generated from firing the shot. The “opposite reaction” reciprocates the slide and runs the cycle of operations to extract, eject, feed, chamber, and lock in the succeeding cartridge.

Recoil is a given in this system, and choices in pistol caliber, model, and specific load can optimize or downgrade the shooter’s overall ability to run the weapon at speed when the moment comes. Most shooters struggle against recoil to some degree, whether it is just an unwanted dwell time to recover the sights to fire the next round, or a physically uncomfortable distraction. We’ll cover a few areas that can help tune recoil to a shooter’s needs.

Every pistol has to recoil to function, but too much can challenge the shooter’s ability to control the tempo of a situation.

Table of Contents

CHOOSING TIME

Recoil is highly subjective. What to one shooter is a pleasant load that allows him or her to run the pistol well may induce a flinch in another. Arthritic joints, an injury or poor interface between hands and sharp edges on the gun may cause a shooter to feel pain with a load that another highly recommends.

Because each shooter puts a different mix of mass, joint alignment and muscular tension into the “shock absorber” that the pistol recoils against to function, mileage varies and absolutes are hard to come by.

Competing pistol designs unlock differently and with differing amounts of mechanical advantage in their grip angle, height above bore, etc, so the information presented is illustrative, not definitive.

Glock 17 was fired for time on plate racks, with fast times and positive control proving why there is such interest in 9mm service pistols.

Attempts to measure recoil in units such as free recoil have never translated well to the layman. However, recoil always translates into time. The greater the recoil and accompanying muzzle rise (the dreaded “flip” that beginners hate), the longer the shooter has to wait to accurately launch the next shot.

Thus, lighter recoiling loads are faster to shoot to the same accuracy standard than stouter ones. To help sort through the data, most shooters can “feel” an increase of recoil that translates to about .04 to .05 second in additional time as a distinct step up. Some (a few) can pick up smaller increments.

TEST SHOTS

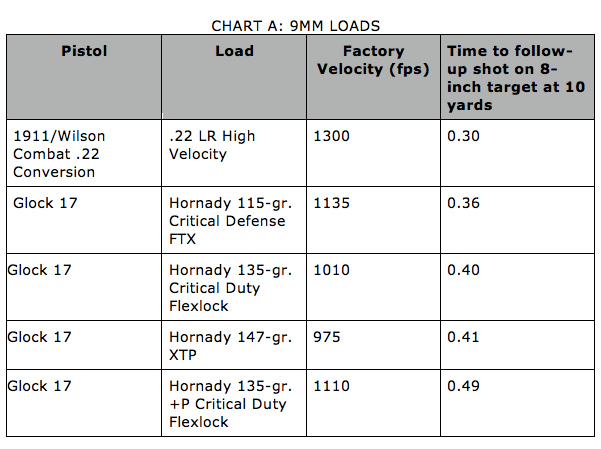

For an example of this, a Glock 17 9mm pistol, as representative a pick as exists, was shot with a roundup of available high-performance loads from Hornady against steel plate racks for time. The eight-inch round targets represent the most commonly accepted dimension for solid, vital hits to a threat. Ten yards ensured that the targets were in a scenario-driven distance while being close enough to guarantee fast hits while distant enough to require the sights to fully recover and align.

As a control, I shot the rack with a 1911 with a .22 rimfire conversion kit on it, a combination of shootable platform and negligible recoil that set the limits of what I was physically capable of at the time of the testing. That limit timed out at an average of .30 second to drive the pistol on to the next plate and trigger the next shot.

Chart A shows 9mm loads that run the spectrum from 115- to 147-grain expanding bullets, any of which are respectable choices. At standard-pressure velocities, the truism that lighter bullets recoil less held firm. The 115-grain Critical Defense FTX loads averaged just over a third of a second at .36, only slightly slower than .22 Long Rifle and near my maximum capability. The lightweight FTXs felt very similar in recoil to the popular Winchester “Whitebox” and similar 115-grain generic FMJ practice ammo.

Adding a magazine extension boosted recovery speed and hit potential in subcompact with +P Black Hills 124 JHPs.

Moving up to the 135-grain Critical Duty load designed to perform against the FBI bullet testing protocol, the 1,010 fps loads averaged .40, adding .04 second per shot for the additional barrier penetration inherent with the heavier projectile. The 147-grain XTP registered .41, with a slightly different feel to the recoil impulse but indistinguishable time.

Stepping into +P with the Critical Duty 135, the time stretched out to .49 second, noticeable by the increased force coming back into the hand as well as the hang time to recover to the next shot, but still not bothersome.

This illustrates the multiple levels of recoil possible even with the 9mm, which is often considered an easy recoiling cartridge. Shooters get off track when they endlessly fret over the ideal, man-stoppingest, zonkers load with no consideration of their ability to control it.

Shooters who practice exclusively with 115-grain ball and then “load up” with the heaviest +P ammo may be in for a bit of a surprise. A span from .36 to a sliver under half a second between the light and +P loads is significant, although hard for many to put in context. Some times to consider: Reaction time hovers for most around a quarter second, while each aggressive step in a lunge or dash ranges from .25 to .35 second.

There is typically 147-grain ball available if one looks, and it has a distinctly different recoil than the 115-grain practice stuff, although both are light. Some combinations of shooter and pistol will prefer the “feel” of one to the other. That the 135s and 147s are subsonic is an additional plus if the shooter is sensitive to noise and blast.

A weaponlight such as this SureFire X300 has a dampening effect on recoil by adding several ounces in a strategic location in addition to low-light capability.

GET A (WHOLE) HAND ON IT

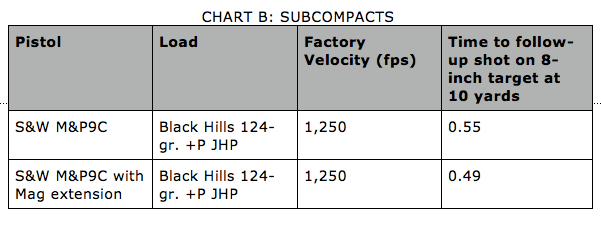

For the subcompact crowd, there is a measurable difference when the little finger is fully wrapped around the pistol and the backstrap is extended. The popular 9mm and .40 service pistols have factory or aftermarket extensions that build up a “grip” onto a full-size magazine that mates with the subcompact frame to give a whole grip when the magazine is inserted.

As an example, I shot an M&P9 compact against the same 10-yard rack. Ammo was Black Hills 124-grain +P jacketed hollow point, a load that has proven phenomenally accurate in the little pistol.

The average in subcompact mode was .55 second shot to shot. Putting the custom extension in place cut .06 second off at .49—very similar to +P performance from the longer barreled Glock (see Chart B).

Between the additional recoil control and purchase to aid in pressing difficult shots, the extensions have a lot going for them besides capacity. Any shooter who carries a subcompact should seriously think about the spare magazine wearing an extension. However, many extensions do not stay put and can slide/inch down when carried in a mag pouch and seriously hinder an emergency reload, so consider a means to secure them in place.

Compact 1911s can be a handful with hardball or heavier loads. Hornady 185-grain Critical Defense FTX toned down the recoil.

HANG A LIGHT ON IT

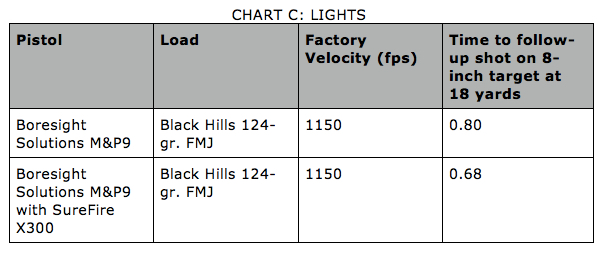

One way to counter recoil is to increase weight out front. A pistol-mounted light does just that while coincidentally adding significant capability when it gets dark. The great majority of service pistols are now available with integrated accessory rails, and the major holster makers have all caught up to mainstream weaponlights.

In this case, a Boresight Solutions custom M&P9 was shot with and without a SureFire X300. Ammo was Black Hills 124-grain standard pressure onto the eight-inch plates, this time at 18 yards. The difference was .12 second, which would approximate a .07- to .08-second difference at the ten yards used elsewhere (see Chart C).

Not reflected by looking at just time is the additional ease of hitting due to the increased weght. With the pistol “slick” there were a number of misses (which were not tallied into the time averages), while the extra weight out front and “thumb rest” offered by the X300 allowed much cleaner trigger presses and 100% hits.

If you haven’t considered a white light for the obvious reasons, consider it as a compensator that lights up the dark. The difference is very noticeable.

Full-size 1911 such as this Les Baer made controlling even heavy +P loads possible with fast recovery.

GO LIGHT

For the big-bore crew, there are options. Many .45 ACP shooters are emotionally wed to 230 grains, which is pure Americana and as proven as a solution gets. But when coupled with compact alloy-framed pistols, the recoil becomes apparent.

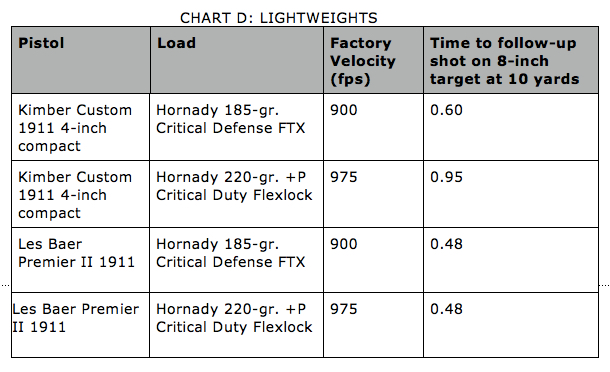

A Kimber Custom Shop four-inch 1911 with the compact Officer’s size frame and slimline stocks was run on the plates at 10 yards for data (see Chart D).

Hardball as a baseline averaged .69-second splits. Hornady Critical Defense 185-grain FTXs felt much better at .60 second, the tenth of a second also corresponding to significantly less thump in the hand. The new Critical Duty 220-grain +P Flexlock was a beast in the little 1911, at .95 second between hits and significant effort to “hang on.” The load has some truly impressive ballistic testing and may be the answer to 230-grain expansion issues in the ACP.

But in lightweight platforms, it is an example of the decision that faces big-bore shooters: go big and effectively launch individual “rockets” at a second per, or back off to something that can be more easily controlled. At nearly one second intervals, there’s a huge penalty for a scant hit or outright miss in a conflagration that might only last a couple of seconds total.

Shooters have to balance the effectiveness of a load and their ability to run it well out of their pistol. Even 9mm has several distinct levels of recoil.

GO BIGGER

Breaking out the full-size 1911 was a different story. A Les Baer Premier II with Burner stocks handled the same two loads at an identical .48 second average. Sounds strange, but that was the result. Where there was a gentle rise and somewhat slower cycling of the pistol with the 185s that was rather pleasant, the 220-grain +Ps cycled sharply and returned to target quickly although rising higher.

With a larger supply of the 185s to really get used to the impulse,

I could probably shave it down a little more, but the results show pretty strongly that 39 ounces and five inches of barrel make a significant difference when shooting the man gun.

That the +P 220s ran at the same speed out of the 1911 as the +P 9s did out of the Glock 17 say quite a bit about the platform’s shootability. The traction of the sandpaper-like stocks is a help as well. Anything that helps secure the pistol in place so the pistol can only flex the wrist as the slide works and not squirt around in the grasp reduces the effect of recoil. The smooth slimline stocks are comfortable to carry but allow the feisty little alloy .45s too much leeway in recoil.

Hornady defensive 9mm loads from 115 to 147 grains were shot for time against eight-inch plates from a Glock 17. They showed three distinct levels of recoil, allowing a shooter to tailor controllability by load choice.

ISSUE FIXES

The givens are that larger pistols, smaller calibers, and lighter loads handle recoil better than the alternatives. Not much surprise there. But all of those may not be desirable or available fixes.

In those cases, there are three tried-and-true options. First, more live-fire practice will allow the body to better compensate against recoil via subtle changes in stance and mass applied behind the gun. One sure fix is for the shooter to put a little conscious “stiffening” of the firing-hand wrist as one would for punching a heavy bag. Adding traction to the pistol by changing grips and adding non-skid or stippling polymer is another nudge toward faster recovery.

The non-shooting fix is to spend time building strength in the hands. Squeezing a tennis ball, working serious grip devices, or crumpling paper until it burns are all used by different high-end shooters to gain mustard to put into controlling the gun.