The AR series is an extremely ergonomic platform, and provides the shooter with a weapon that is controllable in both semi- and full-auto fire.

In order to achieve that, the stock is straight. Earlier military rifles made of linseed-soaked wood and ordnance steel had a sharp drop at the buttstock.

The straight stock of the M16 family required that the sights be placed higher above the line of bore than with preceding U.S. service weapons, with some exceptions. The innovative Johnson M1941 LMG is a prime example, and the M60 GPMG the more common early example.

The higher sight line meant that the shooter could keep his head erect. Keeping the head up meant that the shooter would be looking through the optical center of his eye. That in turn meant better visual acuity, more consistent sight alignment (a major plus with iron sights) and consequently better hits on human targets.

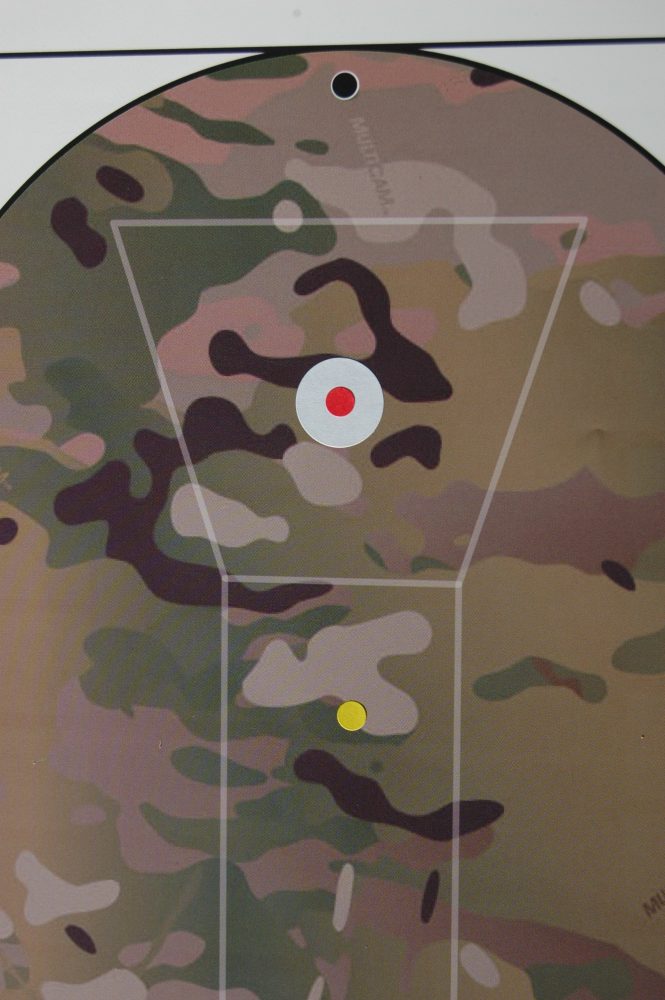

Desired Mean Point of Impact (DMPI) is the red dot within the ¾-inch circle. If you fail to compensate for offset—especially within ten yards—your projectile will strike 2.6 inches below the DMPI (yellow dot). A jaw/neck shot may stop your opponent, but what if his head is only partially exposed, the lower portion being covered by a hostage? To get that projectile where it needs to go, you must compensate for offset and aim 2.6 inches high (about where the little black dot is at the top of the “head.”

For the military (and in the past), the issue of offset was not a problem. The Marine Corps Qual course started at 200 yards, and offset was a non-issue. The Big Army had a more realistic course of fire (relatively speaking), but none of it was close enough to make offset a concern.

Indeed, it wasn’t until the mid 1980s/early 1990s, with the advent of the Counter Terrorist (CT) and In Extremis Hostage Rescue (IEHR) Missions that doctrine writers and trainers even considered that training should take place at close range. For those tasked with such missions, and those tasked with training them for these missions, the weapons chosen for CQB and IEHR were based on their knowledge of the situation and what was available.

Initially sub-caliber machineguns were used for this mission. These included the M3A1 and various flavors of the MP5 in the U.S., and other less common guns in other venues.

The configuration of the M3A1 and MP5 were such that offset was minimal. However, dissatisfaction with the efficacy of the sub-caliber platforms led to the adoption of the 5.56x45mm round pretty much across the board in the military and most police agencies.

So what is offset, and why is it important?

Offset is (in this instance) the difference between the Line of Bore (LOB) and the Line of Sight (LOS). For the M16 family, and dependent on the sighting system used, it is 2.6 inches.

Offset is a factor only at close range, and here is why.

While the eye can be considered analogous to a laser beam (you are looking directly at the target), the projectile launched from your carbine is not a beam rider. The nanosecond that the bullet leaves the barrel, it is subject to gravity and friction. The bullet will immediately drop off of the line of sight, describing a downward arc.

Eight inches is widely accepted as the standard for body shots, and it is large enough to be forgiving. The approximately four inches worth of a face requires more finesse to be decisive. This shooter forgot about offset, and was a tad low on some of his face shots. Would it still work in a life-or-death situation? Probably, but why train for mediocrity?

Therefore, in order to strike a target at distance, the barrel must be elevated to compensate for this. This is done by manipulating the sights.

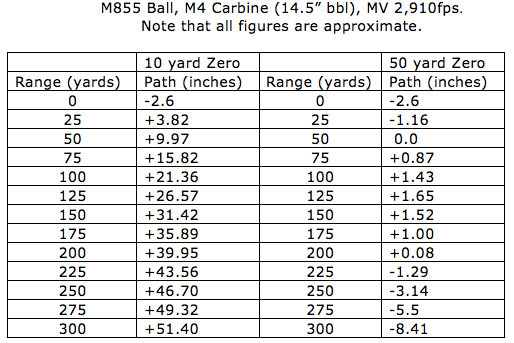

While most of the Marine Corps and Big Army are locked into the 300-yard/meter zero, others within DoD and in most agencies/departments use a 200-yard zero. (Note that this is for an M4 Carbine using M855 Ball, and all figures are approximate.)

Consider that the projectile will start out at 2.6 inches below the line of sight (LOS). It will continue to rise so that at 25 yards it will be 1.16 inches below the LOS, and at 50 yards it will cross the LOS. This is called the initial intersection.

It will continue to rise for approximately 125 yards, at which it reaches its maximum height above the LOS—the maximum ordinate. It will then drop down until it crosses the LOS again at 200 yards (see table for further information).

A 200-yard zero means that from contact distance out to 250 yards, the projectile will neither rise nor fall more than 3.14 inches off of the LOS.

All I need to do is put that dot, crosshair, chevron or front sight tip more or less between his nipples (center mass on a human) and control the trigger straight to the rear.

The 200-yard zero is amazing in its simplicity, though some try to complicate it by introducing formulas that make what should be simple, difficult.

Marine MPs engage a target at the 3-yard line. Speed is paramount, but without realistic accuracy, you may not be able to defeat a human opponent. At 10 yards and in, you need the full value of the offset—approximately 2.6″.

The major advantage of the 200-yard zero is the easy transition from short range to long range shots and vice versa. This translates to easily managing your sightline without having to reconcile distances under duress. This is true if using the legacy iron sights or optical sights.

What does this mean to us? The answer is simple, though the application by some (many) is not. Within a certain distance from the threat, we have to compensate for the offset to ensure an incapacitating hit. That means if I need to take a high percentage shot at 15 yards and in, I need to be able to compensate for the difference between the LOB and the LOS.

Consider this scenario: A hostage taker is holding an infant across the lower part of his face, with a knife to little Muffy’s tiny throat, three yards away from you. As he makes an attempt to slice the child’s neck, you use Deadly Physical Force (DPF) to eliminate the threat to the hostage.

You are armed with an AR/M4/CQBR/whatever, and place the dot, chevron, triangle, crosshairs, whatever 2.6 inches above the perp’s running lights, with the thought of immediate incapacitation.

You press the trigger straight to the rear and the shot is fired. The round strikes the piece of human garbage right between the eyes, with the bullet penetrating his cranial vault. He ceases all motor function, and becomes immediately flaccid, dropping straight to the deck.

At the end of the day, you go home. The infant goes somewhere, alive. The bad guy has ceased being an earthly oxygen consumer.

SWAT Cop Natalie Mendoza takes a single shot to the brain at the Eloy, Arizona Landfill. Can you afford a poor shot at bad breath distance?

White puffy clouds float through an impossibly blue sky. Rivers of chocolate flow through green fields. Trees give beer. All is well in your world.

Consider this slightly different scenario: A hostage taker is holding an infant across the lower part of his face, with a knife to little Muffy’s tiny throat, three yards away from you. As he makes an attempt to slice the child’s neck, you use Deadly Physical Force (DPF) to eliminate the threat to the hostage.

You are armed with an AR/M4/CQBR/whatever, and place the dot, chevron, triangle, crosshairs, whatever directly between the perp’s running lights, with the thought of immediate incapacitation.

You press the trigger straight to the rear and the shot is fired—but where does the round impact? Between his eyes, where you had aimed? Nope, it will strike approximately 2.6” low and hit little Muffy square in the chest. The projectile will possibly also injure and perhaps incapacitate the mutt, but you have just done his devil’s work for him.

Your world, as you knew it, has just come to a screeching halt. You killed the hostage that you were tasked to rescue. You failed in your life’s work. Aside from the moral issues, you are now faced with the (shudder) CNN effect, where the entire world will be able to criticize, for months on end, what you had to do in a heartbeat.

You will be called, at best, a trigger-happy psychotic, a child murderer and a menace to society by the electronic and print media.

Military has come a long way in training since the war started. A lot of training now takes place at closer ranges, rather than starting at 200 yards and more. This target is old school, back in the days when people shot from the hip with their off hand in their pocket. While the kill zone is generous, this Marine has to compensate for offset with his M4 Carbine at three yards.

Scores of Internet addicts, sitting in their underwear and safely ensconced in the darkened basement of their parents’ home while awaiting the passage of puberty, will become instant ex-spurts on all manner of things they have no knowledge of.

Lawyers will be lining up in battalion formation, waiting to remove everything you have ever earned.

Not a pretty picture.

Shift to a different scenario—MOUT (Military Operations on Urban Terrain). A grunt entering a structure with a mission order to eliminate the threats therein isn’t going to be super-concerned with a precision shot at bad breath distance. He will engage with a Non Standard Response (NSR) and shoot the bad guy to the ground.

Having said that, things have a tendency to shift gears pretty quickly in combat, and while fast—but less precise—shooting may be necessary in one room, a high percentage shot may be required in the next. You need to be able to apply the proper amount of force where necessary.

Although training—substantial initial training followed by regular sustainment training—is the answer, some have decided to take a shortcut. To this end, several police SWAT teams and a regional FBI team asked about zeroing their weapons for what they considered to be the statistical engagement range based on past shootings—approximately seven yards. They felt that this would provide a real-world solution, and give the shooter one less thing to consider in a fight.

Terrific out of the box thinking—except that it is flawed. Averages are averages, and make for great reading. However, the world of today is much different than the world of yesterday, and using a 1972, 1986 or 1999 statistic to predict a 2008 event may not be the wisest thing that you can do today.

Shortly after the attack on the United States on September 11, I was contacted by an agency that provides emergency services to several large international airports. They were seeking training, and when I reviewed their equipment, I was surprised to find that they were using 9x19mm ARs.

Their justification was that at “average” engagement distances, the 9x19mm was sufficient. In their minds, maybe so, but airdromes are pretty big places, and taking a shot across a terminal may translate into yards—many of them. The distance between the nose and tail of a 7-whatever-7 is more than I would like to chance with a pistol-caliber weapon.

Somewhere along the line, they may have missed the point that normal prior to 9/11 was significantly different than normal post-9/11.

There is a greater possibility that long-range shots in cities may have to be taken than most would consider, and the potential to use suppressive fire against organized groups might be something we will see sooner rather than later.

It would pay to have the carbine zeroed at a distance that can support both CQB and mid-range shooting. And that certainly isn’t seven yards.

As an example, one high-profile team wanted a ten-yard zero. At 25 yards, the projectile would be 3.82 inches above the LOS. At 50 yards, 9.9 inches above the line of sight, and 100 yards, 21.36 inches above the LOS. See the problem here? If they had to take a 50- or 100-yard shot, would they be able to compensate properly? Would you? While statistics are nice, can you guarantee that your next shooting will be within the statistical average?

Offset is neither good nor bad. Offset is what it is, and those who have to deal with high percentage shots at close range need to understand that it exists, and they have to compensate for it.

For those who believe it is too difficult to handle, may I suggest another line of work? If you are that far behind the power curve, the use of DPF may be way more than you can comprehend.

The application of DPF at body odor distances is a difficult job on the best of days. The key to winning the fight is to develop a warrior mindset and seek out training that is appropriate for your mission.

[Pat Rogers is a retired Chief Warrant Officer of Marines and a retired NYPD Sergeant. Pat is the owner of E.A.G. Inc., which provides services to various governmental organizations. He can be reached at [email protected]]