I started defensive firearms training in 1993, back when the handgun nearly everybody used was a steel-framed Government Model 1911, and the preferred long gun was a Remington 870, Winchester 1300 or Mossberg 500/590 slide-action shotgun.

Back then, the really high-speed guys installed ghost-ring sights on the shotgun and took pleasure in the fact that they were then capable of putting a wheelbarrow load of hurt on a goblin as far as 100 yards away. To us, words like “Kydex, “Magpul,” and “EOTech” sounded like they came out of a science-fiction movie.

A lot has changed since then.

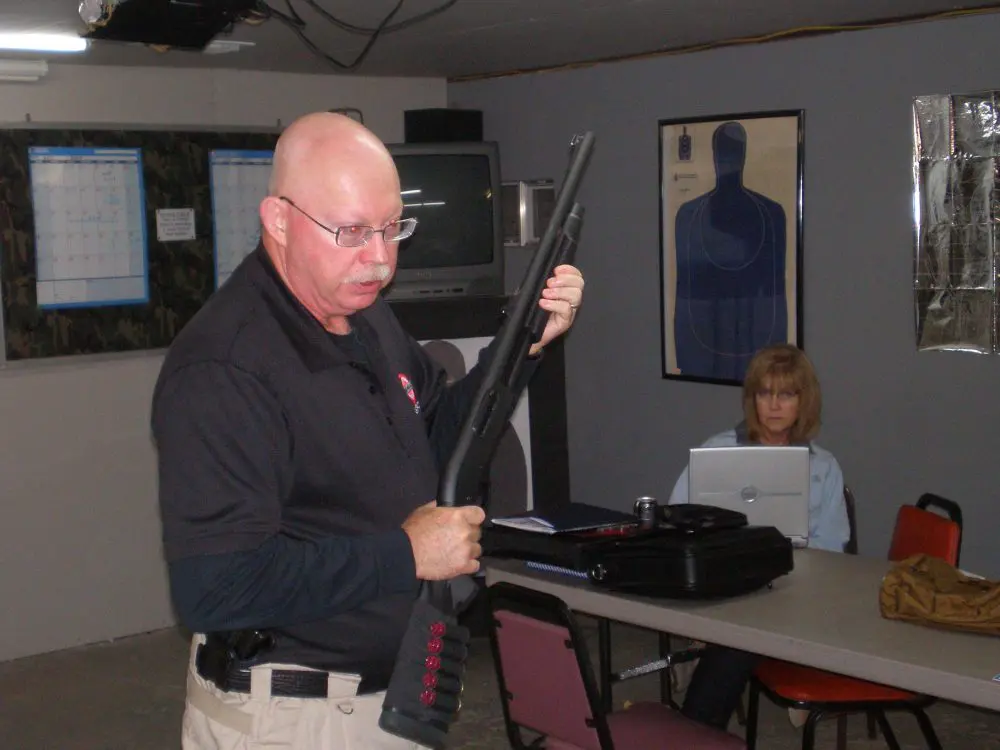

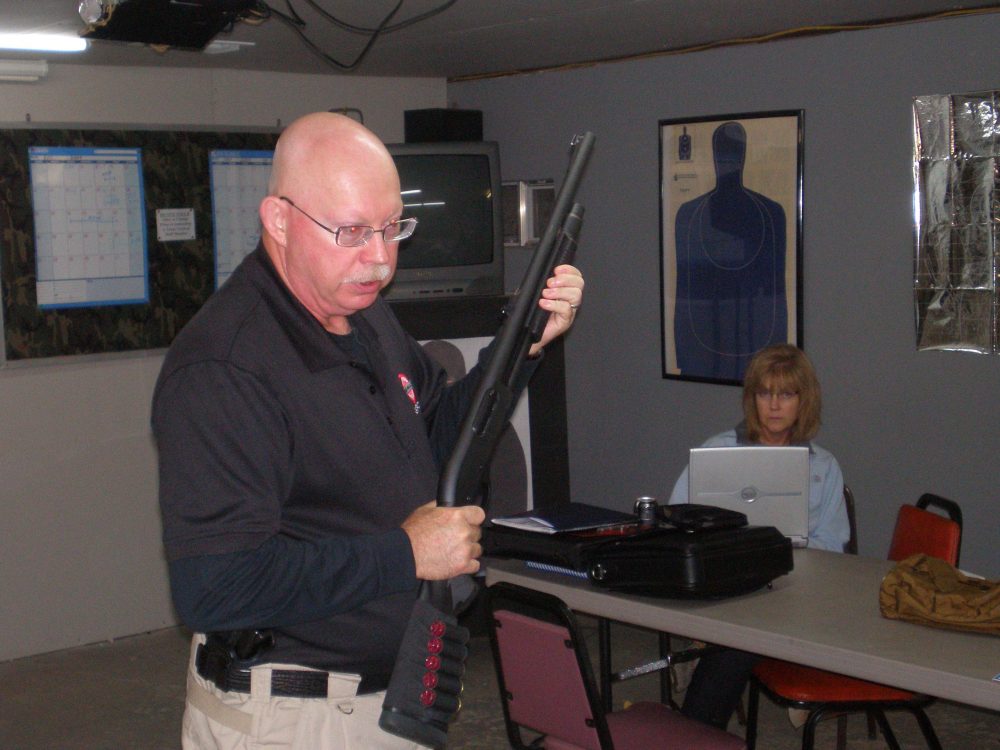

Tom Givens displays his lightly customized defensive shotgun—a Remington 870 equipped with a youth stock to shorten the length of pull—and highly regarded XS Express Sights.

Polymer-framed, striker-fired pistols are now the standard, and the long gun of choice is an AR-15 or similar small-caliber semiautomatic carbine bearing an electronic red-dot sight. Most of us eventually relegated the shotgun to the darkest corner of the gun safe. After all, they don’t hold much ammo, they aren’t that much fun to shoot, and they are essentially a short-distance weapon. In my opinion, they didn’t work as well as we hoped past about 10-15 yards unless slugs were used, and the lobbing trajectory of a one-ounce .76-caliber slug made 200-yard hits problematic.

Perceiving myself as being on the cutting edge of tactical technology, I actually sold all my shotguns at one point, noting smugly that there was no situation that I would ever come across that could not be handled with my AR-15 and Glock 19. On several later occasions I learned that, in addition to pride, ignorance goeth before a fall.

My first brush with wisdom came during a forced entry my team did in which I ran smack-dab into a pit bull while armed only with my Glock (disclaimer: no dogs were shot during the making of this story).

What really drove the message home was going after wounded wild pigs in wooded creek beds after dark during a two-year stint of professional guiding.

Gunwriter Keith Pridgen takes aim at negative target. Any slug or single pellet that struck target outside negative zone was considered a miss. With most (but not all) buckshot, this became a real challenge when distances exceeded ten yards.

On two occasions, I actually tripped over dead pigs that tipped the scales at over 200 pounds. I remember mumbling under my breath while working in such a dark, claustrophobic environment that if I got out of that particular situation unscathed, I would bring a compact slide-action shotgun stoked with 00 buckshot with me the next time I did something so stupid. I also noted the similarities between what I was doing at the time and dealing with one or more potentially violent criminals, where the need to place fight-stopping hits on fast-moving threats in low light was a strong possibility.

I may be slow, but I eventually got around to embracing reality and getting myself and my gear up to speed. I had studied the use of the defensive shotgun under such masters as Louis Awerbuck, John Farnam and Jerry Miculek, so it was simply a matter of acquiring an appropriate defensive shotgun and then knocking the rust off my shotgun skills.

I have done executive/VIP protection and law enforcement duties while working out of cars, and wanted something short and lively. Having recently seen the movie 3:10 to Yuma, I decided to suck it up, buy the tax stamp and go the NFA route, and acquired a Remington 870 with a 14-inch barrel and modified choke. I then shortened the buttstock by one inch despite my orangutan-length arms, added a two-point sling, patterned it with a couple of different brands of 00 buckshot, checked my point of impact with Forster-type slugs, and pronounced myself ready to rumble.

Givens shows positive effects of choosing premium buckshot ammunition. A load of Federal Vital Shok 00 buckshot with Flitecontrol Wad produced this impressive five-inch pattern at 15 yards.

Time eked on, and I became anxious to run my shotty through a class. I have been a firearms instructor for 15 years, but like nothing more than to be a student from time to time in order to obtain an objective assessment of where my skills are, plus pick up (OK, steal) training material from others. I contracted Tom Givens from the nationally recognized Rangemaster school in Memphis to come to north Texas and teach a one-day shotgun course.

Before becoming a full-time trainer in 1996, Tom Givens completed a 25-year career in law enforcement and specialized security work, including patrol, investigative and firearms instruction duties. Tom’s school, Rangemaster, is a full-time academy, teaching about 2,500 new students each year, both in Memphis and on the road. A graduate of the NRA Law Enforcement Firearms Instructor School and Tactical Shooting Instructor School, the FBI police firearms instructor school, Gunsite, TEES, and other academies, Givens has trained with Jeff Cooper, Ken Hackathorn, Chuck Taylor, John Farnam, Clint Smith, and a dozen other notable instructors.

Givens was an active competitor in the early days of IPSC and is a Master in three IDPA divisions. He has written five published firearms textbooks and over 100 published articles in S.W.A.T. Magazine, Handguns, Soldier of Fortune and other publications, and serves as an expert witness on firearms training in state and federal courts all over the United States.

Author was relieved to find that Winchester Ranger slugs were capable of producing this five-shot group in his bead-sighted Remington 870 short-barreled shotgun when fired from kneeling at 30 yards.

Prior to the training day, Tom and I laughed about consumers who would acquire a certain weapon with the understanding that the distance lethal-force encounters take place at would simply magically adjust to accommodate the weapon system wielded by the good guy. Ergo, if you had a pocket pistol, all fights would take place at six feet, and if you had a rifle, they would take place at 200 yards. Reality suggests otherwise.

The bad guy commences the assault at the distance he can accomplish his objective, and this distance is usually within the length of a room or one or two automobiles. To that end, the good guy should be prepared to react very quickly to a threat, have the ability to rapidly get his shotgun into play, and be able to put as much of the shotshell pattern as possible on the bad guy where it counts to quickly terminate the threat. And do this while keeping in mind that every stray projectile that misses the target is capable of injuring or killing innocent parties.

To that end, Tom focused the class on developing an intimate relationship between each student and his shotgun. The first two hours were spent in the classroom covering shotgun selection, outfitting and selection of appropriate ammunition. I was somewhat amazed at the wounding mechanism of buckshot at the distances most attacks take place, and Tom’s methods of teaching accountability for rounds fired at speed were unlike any that I had previously experienced.

Moses prefers Eagle Industries Shotshell Pouch for carrying rounds on his person.

Like any good shotgun course, the first hour on the range was spent learning proper stance and grip, followed by exercises covering ready positions, establishment of weld points (support hand, strong hand, cheek and shoulder), sight picture and alignment, trigger control, follow-through, vigorous working of the slide action on pump shotguns, and reacquisition of the target.

I would be remiss if I failed to mention that Tom continually stressed the importance of keeping the shotgun loaded, and it was pleasantly soothing to hear him repeat the old mantra: “Shoot one, load one, shoot two, load two.”

Good stuff, but I had been there and done that, and it was nothing to write home about for an experienced shotgunner. However, the beginners in the class would beg to differ, as most of them had never taken any kind of defensive shotgun course, and I noted a vast improvement in their gunhandling abilities by day’s end.

Then, the class got very interesting. Tom works off the following theory when it comes to teaching shotgun skills: negative targets equal positive results. Thus, Givens uses the concept of negative targets to teach students to mate precision, speed and proper ammunition selection. Suddenly I was challenged.

Dr. Patrick Jones rapid fires his 870. Students were taught to firmly cycle the slide action while the shotgun was recoiling in order to deliver multiple shots at high speed.

Tom takes a standard cardboard target and then cuts out that portion of the center that would house the heart and lungs on a real-life adversary. The objective then becomes to drive every round, buckshot or slug through the negative target zone, and Givens considers every penetration outside of this zone to be either a failure on the part of the operator, the ammunition selected or both.

I found myself working very hard in speed drills to meet his standards, and soon cursed myself for being somewhat lackadaisical when it came to selecting buckshot for the course. At 15 yards, my modified-choke 870 would not keep pellets inside the negative zone, and I was using reduced-recoil 00 buck made by a major ammunition manufacturer. Fortunately, the Winchester Ranger Reduced-Recoil slugs performed much better, with my bead-sighted shotgun shooting very near to point of aim at 30 yards.

Student Mike Marneris firing five rounds through Rangemaster negative target. Drills of this nature, which stressed time and accuracy, were very useful for teaching students how to get the most out of their shotguns.

Tom is an instructor’s instructor, and he was not about to present us with a problem without offering a solution. Givens is a major advocate of Federal Premium Vital Shok 00 buckshot with the Flitecontrol Wad. As I understand it, this wad actually remains with the copper-plated buckshot for up to ten yards from the time the shot leaves the barrel, resulting in a much denser pattern.

We saw this demonstrated repeatedly with nearly every shotgun in the course, and it is my highly fallible opinion that it may no longer be necessary to carefully match a particular load with a particular shotgun in order to get the best pattern possible. My own 870 was throwing 10- to 12-inch patterns at 15 yards with every other manufacturer’s 00 buck that I had until I tried Tom’s preferred load, which graced me with a six-inch pattern at 15 yards.

The end result was a new focus on my part to make sure that I hit my target as close to dead center as I could every time, while being ever mindful of the outcome of a slightly pulled shot or failure on my part to consider the effect of distance. Once I had worked out all the bugs associated with ammunition selection, I was entirely free to problem-solve my way through the rest of the course, including variations of the old Rolling Thunder drill and Tom’s Defensive Shotgun Qualification Course of Fire.

Without going into great detail, the course tested our ability to manipulate the shotgun, shoot accurately (shots only counted if they impacted the negative zone), and load the shotgun in a series of timed drills.

One round of Federal Vital Shok 00 with Flitecontrol Wad fired at 15 yards.

For example, one string called for loading the shotgun with two rounds and standing at High Ready. On the signal, we were compelled to engage the negative zone of the target with two rounds, side-step, reload with two rounds, and engage the negative zone of the target with two rounds—all in ten seconds or less. Let’s see: wait for the beep, shoot accurately, reload, and shoot accurately, all with no real concept of where you were within the allotted time frame. Slugs were used from 15 to 25 yards, where abbreviated time frames made precision shooting tricky. Good stuff!

Initially I believed Tom would teach a good shotgun course that would get me back in tune. I was wrong. Tom taught a great shotgun course using methods I had never considered, and I walked away far better off than when I’d arrived at the range.

In summary, the shotgun is far from dead and is in fact the weapon of choice under certain circumstances. As much as I love my rifles, I could probably make it through the rest of my days armed with little more than a properly set up shotgun, some selected 00 buck and slugs, and my Glock.

The gear and gun geek in me cringes to admit that maybe simple really is good.

SOURCES:

Rangemaster

Dept. S.W.A.T.

2611 S. Mendenhall Road

Memphis, TN 38115

(901) 370-5600

www.rangemaster.com

Eagle Industries

Dept. S.W.A.T.

940 Biltmore Drive

Fenton, MD 63026

(888) 343-7547

www.eagleindustries.com

Federal Cartridge Company

Dept. S.W.A.T.

900 Ehlen Drive

Anoka, MN 55303-7503

(800) 322-2342

www.federalcartridge.com

XS Sights

Dept. S.W.A.T.

XS Sight Systems Inc.

2401 Ludelle

Fort Worth, Texas 76105

(888) 744-4880

www.xssights.com