A reader recently wrote in to request an article detailing lubrication tips in different environments and across different platforms. This is a great question and a topic worth diving into.

Poor lubrication was a leading cause of stoppages at every military shooting school where I’ve worked. It is far too common to see a poor understanding of proper lubrication among even good shooters.

The market is “flooded” with lubricant choices. In fact, if you tried a new unique lubricant product every week, you could probably shoot for three years before sampling them all.

If you added the various automotive and industrial lubricants that some shooters swear by, you could shoot for another year with an oil or grease per week. Across a span of hundreds of products that include petroleum, synthetic, and naturally based mixtures, it is dangerous to generalize. But some broad statements apply across the board.

Table of Contents

LUBRICATION GENERALIZATIONS

Clean and bone-dry guns will typically fire through a magazine or five without issue. Some designs are very tolerant and will run for quite a while dry. Others less so.

Emphasis on the clean part. That is pretty important. No, it is hugely important if one insists on running guns dry. Just because you cleaned it three summers ago may not mean the arm in question is still actually clean for the purposes of “clean and dry.” That a gun will run clean and dry is more insurance than good practice.

On the other hand, a dirty gun that is dry is a bomb with the fuze lit and sputtering. It may very well work as intended for quite a while, but at some point the action will begin to get colicky. In extreme cases of neglect, the gun will go beyond the hiccups to shutting down.

I’ve seen guns bind up and no longer cycle from the combination of dirty and dry, or seize where the crud hardens and no longer allows the action to unlock. The good news is that the weapon often gives the shooter a healthy number of tactile clues before getting to this extreme. When the weapon doesn’t feel right upon cycling the action, the wise man investigates where the fool keeps shooting.

At this early stage of dirty, the judicious application of wet stuff usually keeps the gun running. Judicious here means targeted to where it matters, which we’ll cover later. Fortunately, at the “Oops, my XT 37 is dirty and feeling raspy” stage, almost anything that claims to be a lubricant for any purpose will remedy the immediate problem and get the gun back on the firing line.

My good friend Pat Rogers has written previously of applying a wide variety of non-standard liquids to students’ guns to get the rifles up and running. The “anything wet and slippery” approach is a short-term immediate-action fix, though—it may very well lead to other problems downstream as the liquid bakes off, reacts with carbon/debris, or gums up.

But if a quality weapons lubricant is regularly applied, the dirtiest of guns will often chug along until the sludge and grime reach an almost comical level (FILTHY 14: Bravo Company Carbine Goes 31,165 Rounds, October 2010 S.W.A.T.). It is entirely unfair to the fastidious obsessive cleaning lot that the gun tends to respond better to slippery filth than loving dry spotlessness, but that is the way of things.

Sludge is all good on a training gun or recreational piece, but such practice would quickly get you on the outs with any team of professionals. However, high-end units have a tolerance for “functionally clean” and well-lubed weapons that would just appear dirty and undisciplined to the white-glove inspection crew in other units. As one member of a special mission unit told me, “You don’t want to clean the luck out of it after a good hit!”

COCKTAIL PARTY

The many lubricants on the market have different properties that are directed at cleaning, lubricating, or preventing rust on the weapon. Some claim to do all three, some actually do, and others are single purpose.

It is important to note that from the simplest gun oil to the most advanced mega-hyped snake oil, lubricants can have radically different compositions and go about their job in different fashions. How they do all that is a sure way to fire up Internet debate teams. Comparative performance in your guns, weather, and intended role are the truth tellers.

But because of the wide disparity in chemical makeup and approach, it is best to clean and degrease a weapon thoroughly before switching lubes. Otherwise the remnants of lube A may actively work against the application of lube B and you end up with a gummy mess. You might compare it to pouring lemonade into the thermos that has the dregs of your morning coffee; it will be a drink but neither lemonade, coffee, nor good.

Of course it is equally possible that two lubricant products go together like peas and carrots, and you have a happy cocktail in your blaster. No guarantees, so the sure bet is to start fresh.

WHERE DOES IT GO?

I’ve seen countless numbers of shooters befuddled as to where to squirt the lube, and a healthy crowd rubbing oil on non-moving parts while ignoring the reciprocating ones. There are a lot of weapons in service that have 90% of their lube content in places that don’t “need” it, and any lube in the sweet spots is likely seepage and runoff.

No judgment. I’ve gradually changed my lube regimen over the years as I’ve gotten more time on different platforms. The big reveal is that all magazine-fed repeaters share common lubricating points. A drop or two in these common areas and the shooting can continue while the targets and ammo last.

The two primary areas that need the slicky juice are 1) the parts that contact as locking and unlocking of the action occurs and 2) any parts that rub as the action reciprocates. The parts that contact to facilitate locking/unlocking benefit the most from lube. Pay close attention here, as many shooters get this backwards and focus on the parts that contact as the action cycles rather than locks.

If you’ve ever liberally squirted the rails on a 1911 and neglected the locking lugs, I’m talking to you. Don’t take it personally: Chances are your holster gun still worked fine, just not as smoothly as if you had reversed the priority. Don’t believe it? Rummage through your safe and find the dirty one you’ve been meaning to clean. Put the tiniest partial drop just where the action locks and feel the difference.

The great part is that this applies across every magazinefed platform I’m familiar with, from lever-action rifles to ARs, Glocks and M9s. Smartypants in the back smugly pointed out that blowback pistols don’t lock and therefore disprove the statement. This is correct and relevant only to fictional spies and anyone else who is carrying a blowback .380.

The time-tested method of looking for high point wear or bare metal shiny spots to rub oil onto typically applies to the reciprocal travel of the bolt, slide, or action parts and remains good advice once the locking area is lubed.

With today’s metal treatments, platings, and finishes, this isn’t always as obvious as in the blued steel era. The fix is to look at the pathway the action takes as it cycles. What parts come in contact? How much contact and friction occur? Anything that causes friction will likely benefit from a smear of the oily fingertip.

In lubricating the pathway, shooters often overdo it, leading to messy overruns that can attract gunk in inopportune places. Keep it classy and precise. With the better lubes on today’s market, the product stays in place and works long after the lube of yesteryear would have run or burnt off.

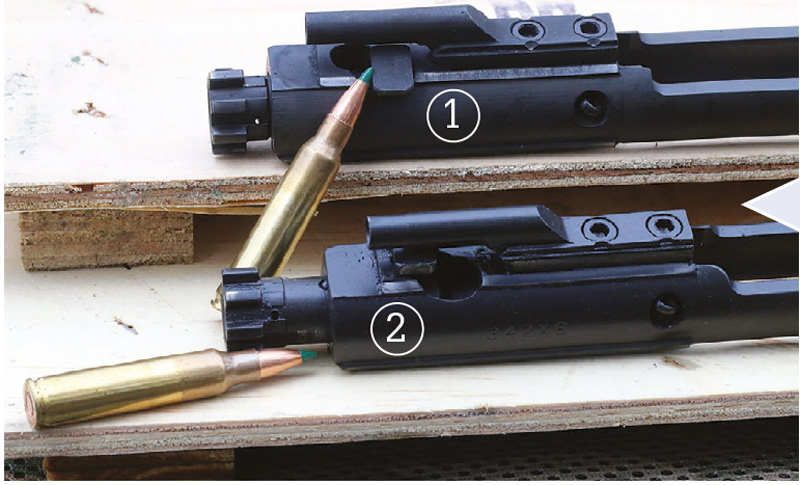

The accompanying photos show the critical lubricating points across the more common platforms. Look for the Black Hills 5.56mm 77-grain Tipped Match Kings that are pointing to the points where a small drop should go or a tickle from the oily fingertip will do the most good.

In order to get to the heart of the matter, we’ll run through them under the premise “if you only had three drops to make it work.” Each of these platforms runs well with three drops of good stuff for a hard day’s shooting. This is for clarity and not to suggest there’s anything amiss with using more.

AR PATTERN

The treatment is the same regardless of caliber or gas system length. Some of the newer platings and finishes are less needy of regular lubrication than the milspec phosphating, but I use the same basic routine regardless.

For initial treatment, I rub a drop of oil around the circumference of the bolt where it slides into the bolt carrier upon locking, and I hit the locking lugs with the slippery fingers while I’m at it. I next roll a second drop of oil onto the shaft and head of the cam pin, with excess hitting the edges of the cam pin hole in the carrier. The third drop gets rubbed along the rails and underside of the carrier where the drag marks are. Any excess on the fingers coats the bolt carrier itself, focusing on the area around the indentation and vent holes. This is more to ease cleanup and reduce carbon buildup than to improve function.

In-stride reapplication with the rifle assembled can be as simple as hitting each of the vent holes with a drop of lube and then dropping a third onto the junction of bolt and carrier. Cycle the action a few times to move the lube into the right places and feel for improvement.

GLOCK

This applies broadly to similar striker-fired pistols, such as the S&W M&P, where the pistol locks at the junction of barrel hood and slide, and there are small rail sections in the frame. This pistol design is one of the least “thirsty” out there in its need for lubricant.

I’ve seen quite a few newer shooters, whose experience is rooted in Glock pistols, who don’t lubricate their pistols at all and haven’t suffered for it (yet). Not ideal, and these shooters almost universally run into issues when they carry that practice into other platforms.

One drop at the hard angle on the front of the barrel hood, with the excess rubbed onto the corresponding locking area at the front of the ejection port will do a lot of work. A second small drop gets rubbed around the circumference of the end of the barrel where it settles into the slide. The third gets split and rubbed onto each of the rail sections in the frame, and the excess wiped down the underside of the slide where the drag marks are.

If my finger is still oily, I hit the contact point on the trigger bar that engages the firing pin safety and swipe across the safety itself. Reapplication tends to be a single drop on the barrel hood with the slide racked a few times to work it in. At this point, feel determines any additional required.

BERETTA

The following is specific to the Beretta 92/M9 series. A dry and dirty Beretta often acts up after a couple hundred rounds, particularly with government ammo, which is considerably dirtier than typical blasting ammo.

This is partly the root of its spotty rep with veterans—the primary cause being shoddy contract magazines and outsourced replacement parts.

The upside is that one drop on each lug of the locking block keeps the Beretta humming for a case of ammo. The 92 series is a remarkably smooth-cycling gun when properly lubed, and it only takes a couple of drops targeting the locking block—specifically the wing-shaped lugs—to get it most of the way there. The third drop gets rubbed along the rails, with the excess rubbed down the underside of the slide, targeting the firing-pin block.

A couple times per year, or maybe twice per deployment (weather dependent), the M9 benefits from a tiny drop of oil on the underside of the slide where the safety rotates. Keeping the safety lubed from the inside makes it hugely faster and more reliable to disengage as part of the drawstroke.

1911

Generalizing about 1911s is dangerous due to 105 years and dozens of makers’ worth of variations in tolerance, modifications, and quality. The design can function pretty well with minimal lube in rattle-y, “combat accurate” GI surplus format, or need a regular diet of more than three drops of very specific lube in custom tight-fitted match-gun mode. We’ll focus on a modern carry-grade five-inch pistol as reference point.

The 1911 needs every bit of three drops of good lube. The design is happiest wet. One good drop goes in the locking lugs, with the excess smeared around the corresponding recesses in the slide. The remaining excess on the fingers goes on the inside of the barrel bushing and around the barrel’s circumference. Drops two and three go along each rail, with the excess rubbed specifically on the disconnector and down the underbelly of the slide. The tiniest dab of oil on the plunger that the thumb safety hits is a great idea. It happens very infrequently, but I have seen this part get a barely visible speck of rust and lock the gun hard into on-safe. An ounce of prevention is wise here.

WEATHER REPORT

The old M16 series Technical Manuals had guidelines for weather and environmental conditions. These remain a valid baseline. They stipulated minimal lube for cold or dusty environs, normal lubrication for most environments and typical weather, and heavy lubrication for jungle and other highhumidity locales.

In extreme cold, defined as -10F and below, the TM dictates that all standard lube be removed and replaced with LAW (Weapons Lubricant, Arctic). Extreme cold is tough on any lubricant and is the one situation when (minus LAW) a clean, dry gun may be preferable to an otherwise great lubricant.

Most pros follow a similar path to those guidelines. But with the quality and staying power of today’s better lubricants, the degree of difference can be subtle. Since the pros are very specific in regard to which areas they are hitting with oil, the difference between “light” to not attract dust and “normal” may escape the casual shooter. Heavy lubricant for wet conditions is more about preventing rust than facilitating function.

The wide disparity in market offerings can start to show up as the mercury rises and falls or the wind starts blowing rain or sand. It’s always a good idea to carefully inspect and feel the action as the environment changes. See if your lube is still there and doing its job.

With some products, as the weather drops or the dust blows, you may accumulate sticky “boogers” of what was oil that become counterproductive to function. Caveat here: just because your favorite lube does great in the cold on your handgun doesn’t mean it will on your rifle or shotgun. I treat every weapon system suspiciously as the weather or environment changes until I have enough data to support confidence.

Functionally clean and slicked up in the right spots, your favorite guns will shoot smoothly and well until your ammo budget goes bust.

Whether you take advantage of the new high-performance products or simply splash some motor oil in the right nooks, the gun will run better if the locking surfaces and the action’s path get a little lube.

Good luck and good shooting!