We need to understand that the military, police and average earth people all have different needs and requirements. Very few average citizens have ever used a carbine to defend their life or the life of a third person.

Cops rarely use Deadly Physical Force, but those in tactical teams are more likely to use carbines or sub-caliber machineguns because they are more likely to encounter armed perpetrators involved in desperate situations. In the military, the Infantry does the majority of the fighting, but there are others—Special Operations Forces, armored vehicle crewmen, engineers etc.—who also fight at close quarters.

Shooter is on target and preparing to fire. He has a sight picture through his Aimpoint M3, and his finger is on the trigger.

The military, police and citizens all have different laws, rules and regulations governing their use of force, and it is absurd to try to cover all eventualities in a magazine article—or in one class. Where you live and who you work for are the arbiters of what is and what isn’t permissible. Make yourself aware of what those particular regulations are, and understand that when the smoke clears, it is ultimately you who will be responsible for the shots that you fired.

Shooting, in and of itself, is useful only to competitors who are engaging pieces of paper. Gunfights require a lot more than just shooting, but understanding that is sometimes difficult for those on the sidelines.

Table of Contents

THE COMBAT TRIAD

The Combat Triad, as taught by Lt. Col. Jeff Cooper long ago, consists of Marksmanship (the ability to hit), Manipulation (the draw stroke, loading, malfunction clearing etc.), and Mindset (the state of mind that permits winning a fight). All are intertwined, and all are necessary. The Triad works for most, but perhaps not for all, so some instructors are teaching it a little bit differently for those who go in harm’s way as a job requirement, placing mindset and manipulation together, and adding Tactics to the mix.

Shooter is in Post Engagement sequence, in the “Ready” position. Immediate threat has been handled, and he is breaking tunnel vision. Carbine is slightly lowered and he is looking over sights in order to maintain situational awareness. Trigger finger is straight, but ready to engage additional threats.

MARKSMANSHIP

Marksmanship—the purely technical aspect—is the easiest to teach and learn. Aligning sights and controlling the trigger straight to the rear without disturbing the lay of the sights can be learned relatively quickly.

MANIPULATION

Manipulation is something that most have difficulty with. The reasons are manifold, but may have to do with the fact that much of our weapons manipulation skills come from the competitive side of the house. Prior to the First World War, the marksmanship skills of the U.S. military were abysmal, and they had to go to civilians to learn how to actually shoot. The NRA was a major part of that, and the National Match Course was a way to get that done. That course has survived relatively intact today, and while it is a wonderful game, it bears no resemblance to fighting. Specifically, the manipulation taught in High Power is unique to High Power, and has nothing to do with gunfighting. Manipulation is extremely important in a fight, as skill sets built in training need to be executed under highly stressful conditions.

The majority of people don’t know what a fight is like. Fewer still can truly comprehend that under stress you won’t get any better. The best you can hope for is that you will default to your level of training. If your training was poor or if—like most—you have never been trained, you are way behind the power curve. You may not lose just because your opponent makes more mistakes than you, or your juju just happened to be very good when the ball came into your court.

SWAT cop Steve Sheldon during nighttime shoot house exercise. Steve is communicating with his partner after engaging a threat. Weapon is lowered off of sighting plane, and he is assessing over top of sights rather than through them. Trigger finger is straight, and he is maintaining situational awareness.

MINDSET

Manipulation and Mindset are so close that they can, at times, be difficult to separate. A great many whose only connection to fighting is what they see on the silver screen cannot relate to how fast and violent a real fight actually is. Donny Muldoon, my former partner in the 9th Precinct and easily the best cop ever to pin on that shield, put it very succinctly, “The first time someone lays their fist into your snot locker, perception becomes reality.”

In every class I teach, I ask how many have ever been punched in the face. While the percentage of cops and military is very high, apparently a great many others have never engaged in a fight with another human. Without experience, you have to depend on theory. Your theories may be based on fantasy, someone else’s perception of reality, or what a great many rely on—luck. And while having luck on your side is always good, real luck can be defined as skill plus opportunity.

Few people have the “mean gene” in their bodies. Most can get worked up enough to get really angry about something, but few have the ability to do it cold. Your shooting ability counts for a lot in a fight, but your fighting ability counts for much more.

For those in the business, I’ll make a strong recommendation to attend one of Lt. Col. David Grossman’s Bullet Proof Mind lectures. He is a motivating teacher and makes an exceptionally good presentation. He is the author of several books: On Killing and On Combat should be required reading for everyone, regardless of their job title.

Back to the subject at hand.

THREE RULES OF TARGET ENGAGEMENT

These are Three Rules of Target Engagement:

- Target Acquisition. Target Engagement begins with Target Acquisition. The eyes are the primary receptors and the information that you receive will be primarily visual. You have to be able to see the threat in order to hurt him.

- Target Identification. You need to identify the target as Good, Bad, or Unknown. Some military units use a color code for this—White, Black or Gray respectively, but you must be able to do this quickly and correctly.

- Target Engagement. You must be able to engage the threat (Bad Guy) efficiently and rapidly, applying the principles of combat marksmanship in accordance with appropriate law or Rules of Engagement (ROE). If you cannot positively identify the target as a Bad Guy, dominate them verbally.

Pretty simple, huh? While shooting is a mechanical exercise, fighting with the gun requires a combination of mechanical competence with a mindset that is sufficient to win the fight. I am not interested in surviving. People lose and survive, and that is not good enough. I want to win. Second place in a gunfight is nothing more than first loser.

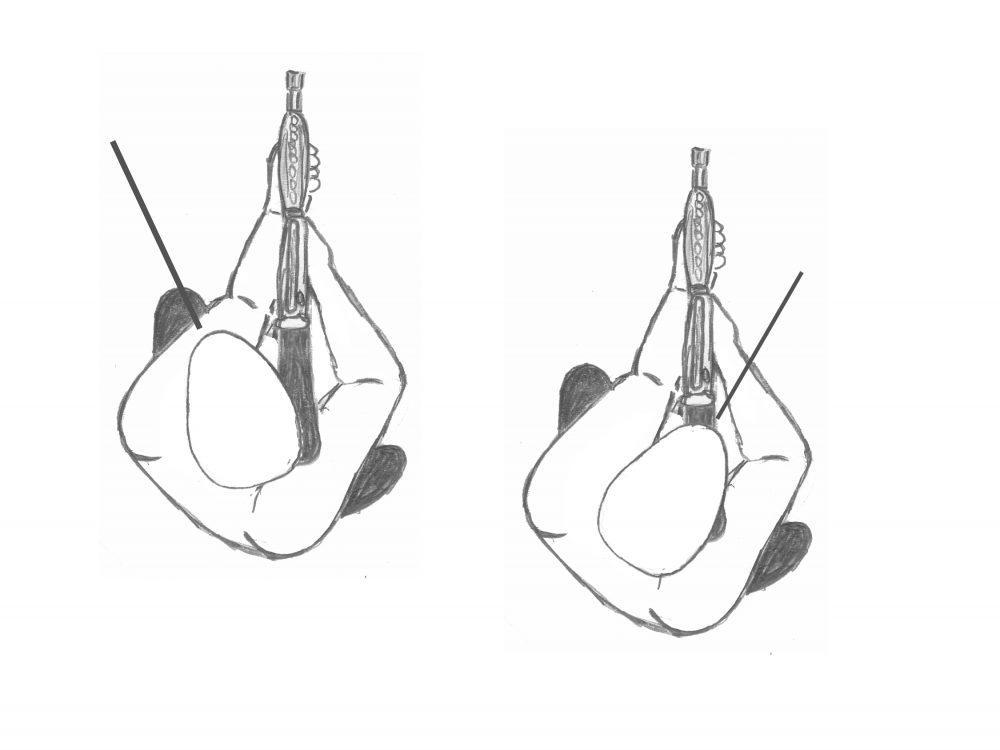

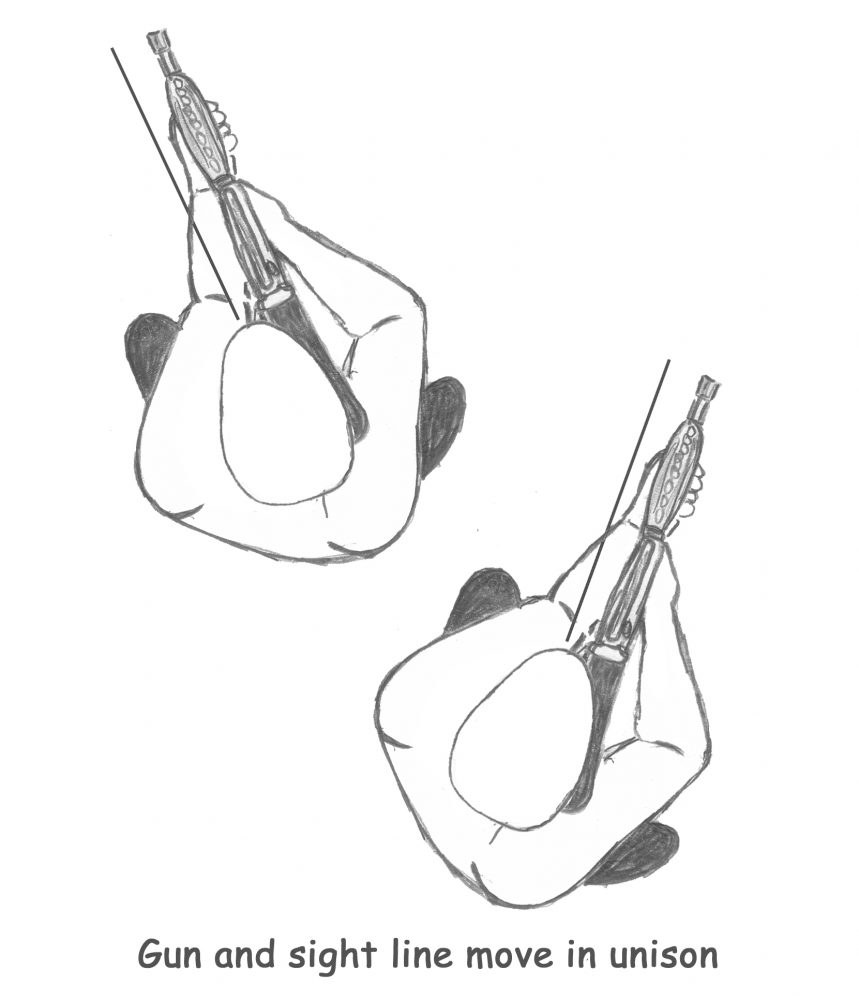

Weapon Stationary: Head and eyes move to cover danger areas. This is a fast way to assess, but useless when using white lights. Drawing: Sue Mogle

TARGET ACQUISITION

Target Acquisition is generally a difficult task. Mid- to long-range threats may be difficult to see because of meteorological conditions, intervening vegetation, camouflage or a lack of target indicators coming from the bad guy.

Close-range threats may likewise be difficult for most because they are not prepared for the violence and speed of the fight. All you have to do is look at the electronic news media and listen to the sheep bleating after a calamitous event: “I couldn’t believe that this was happening to me”; “It was just like a movie”; “I thought it was a prank” and other such nonsense. Their sedentary lifestyle—coupled with the admonitions of an unknowing and uncaring political machine—lulls most into a false sense of well-being.

TARGET IDENTIFICATION

For those who look at the world with a cynical and stable eye, acquiring a potential threat is sometimes surprisingly easy. The issue now is to identify him. Is it what it seems to be? Is that person with a gun a bad guy or a good guy? The identification phase may be based on a variety of inputs. These may include but are not limited to location, uniforms or other clothing indicators, presence of a weapon, type of weapon, manner in which the weapon is displayed, previous intelligence and other information.

TARGET ENGAGEMENT

Once the acquisition has been accomplished and identification made, you need to be able to rapidly and efficiently process that threat before you or others are injured or killed. If your training has been good, if you have a solid grasp on the Color Codes of awareness and if you have already identified the mental trigger beyond which you will use force—to include Deadly Physical Force (DPF)—then you may be on the leading edge.

Don’t wait until your opponent fires the first rounds in a gunfightto engage in a internal debate about the morality of using DPF against another, thinking about what the kidlets and the neighbors might say (and they will say a lot…), asking yourself if you really want to get involved and so forth. Your decision to use DPF needs to be made up a long time before you ever have to press on another human. The middle of a gunfight is a lousy time to play catch up.

WINNING FACTORS

Successfully engaging another is dependent on a great number of things. Foremost is your mindset and your will to win, no matter the consequences.

Tied in with this is your competence with the weapons system. Proper initial training followed by regular sustainment training will provide you with confidence in yourself and your equipment and the competence to use it while you are under fire.

What you use is directly related to how you use it. Some weapon systems are ergonomic—the AR series, for example. The AK is often touted as being ambidextrous and it is—it is difficult to get into action no matter what your dominant paw is. However, with proper training, each will work well in a fight.

Your ability to use the sights may be the difference between winning and having a memorial softball field named after you. Pistols carried for real world use will generally have iron sights. Carbines may have irons or optics. If you are using iron sights on your carbine, understand that you need a clearly defined front sight tip, centered within that rear sight aperture. Optical sights are faster, and placing that red dot/circle/triangle/crosshair on the portion of the body that you wish your bullets to penetrate is a simpler affair.

FIRING SEQUENCE

The firing sequence should go something like this:

- Acquire a sight picture

- Control the trigger straight to the rear

- Follow through

- Re-acquire a sight picture

- Ease to reset the trigger

- Repeat as necessary

SPEED VERSUS PRECISION

The amount of precision and speed necessary are directly related to the distance of the threat as well as the number of opponents facing you.

The closer you are to an opponent, the less precision you need. A flash sight picture (for iron sights) may be all that you need. What you will need is speed.

Several years ago I was talking with the late Lt. Col. Jeff Cooper about the lion he killed in Africa. The critter wound up closer to Jeff than anticipated, and when he brought his rifle up, he was unsure as to where the crosshairs were in relation to the body. He shifted his rifle and stated that when he saw only teeth in the telescope he knew it was time to press the trigger.

Question: How much time do you have in a gunfight?

Answer: The rest of your life.

At distance, you will need more precision, but you may also have more time in which to solve your problem.

Speed and precision are in inverse proportion to each other. Close shots require more speed and less precision. Farther shots require more precision and less speed.

SIGHT ALIGNMENT VERSUS TRIGGER CONTROL

At one place where I worked, the mantra of some instructors in regard to poor shots was “Front Sight.” While that front sight, rear sight, red dot, amber triangle, cross hair or donut are important, the error most make is in controlling the trigger straight to the rear. It can be accomplished slowly and smoothly (as in distance shots) or rapidly and smoothly (as in close shots), but bringing the trigger straight to the rear is paramount.

No amount of sight alignment will carry the day if you clench your entire hand, slap the trigger and send a shot whizzing down at 5 or 7 o’clock.

The point here is that unless you train regularly, at various distances, against single and multiple targets, you will never know exactly how much of each to apply.

DELIVERING SHOTS

In the September 2003 issue of S.W.A.T. Magazine, I wrote a story titled Rethinking the Target Engagement Sequence. I’ll touch on a few salient points concerning how shots are delivered to make sure that we are all on the same page.

A single shot is generally a high percentage shot, used to immediately incapacitate someone (a shot to the brain, for example) or when the only portion of his anatomy available is small (elbow, feet, etc).

A controlled pair is used past 15 meters with the carbine. Consider it to be two single shots, with a sight picture for each one. The split—the difference in time between shots one and two—will be somewhere around .75-1 second. A controlled pair is generally used for center mass shots—that is, the upper chest, at approximately the nipple line.

A hammer pair is two rapid shots with one sight picture. Generally hammers are delivered within 15 meters, though some have the ability to carry it back farther. The split on the hammer pair is typically under .25 second.

A failure drill is a hammer to the chest followed by a single shot to the brain. This drill is commonly used when shots delivered to the chest fail to produce the desired effect—a stop. The reasons why two rounds to the chest won’t work are complex, but can be everything from body armor to the fact that you have the equivalent of Wild Bill Hickok hanging off the end of your barrel. This is a standard engagement drill for some organizations.

Some argue that brain shots are difficult to make under realistic conditions. That is true, but it can be accomplished and is in fact done on a regular basis. If the shot misses the brain but still connects with the head, you have put your opponent in a position where he may not be able to effectively fight, even if only for a short while.

You have just bought yourself time. Use that time efficiently and deliver the brain shot before those spermatozoa floating in front of his optical nerves dissipate and he starts seeing you through his sights.

The Non Standard Response is a series of rapid shots center mass, in those circumstances when a failure drill is contraindicated. This may include a moving threat, near contact distance and others. In this case you have a continuous sight picture while delivering a series of rounds into your target until it is no longer a threat.

Regardless of your MOS, job title, vocation or frame of mind, you are responsible for the terminal resting place of each and every round you fire. Use the Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTP) that are appropriate for the occasion.

POST ENGAGEMENT SEQUENCE

It ain’t over ’til it’s over. Once your opponent is down, you cannot quit fighting. This is a concept that is difficult to convey, especially (but not exclusively) to hobby shooters and competitors, who will, at the completion of a specified drill, engage the mechanical safety and disengage the brain housing group. They will zone out, perhaps delving into some parallel dimension, and ignore everything.

Situational awareness must be maintained. You need to do several things if you want to continue to stroll among your peers. First and foremost is that you must break out of tunnel vision, something that occurs when that chemical cocktail is dumped into your body. If your primary focus is on the opponent you just dumped, you have switched roles from being a warrior to being a target.

Just because someone is down, don’t for a minute believe that he is out of the fight and no longer a threat to you. Jason’s Rule is in effect, and a lot of supposedly dead opponents have suddenly become re-animated. A good rule of thumb is that unless their head is severed from their body or you can see their brains eviscerated, treat them as a potential threat (this is why most police agencies immediately handcuff a perpetrator who has been shot).

However, you need to be prepared to immediately fight someone else. Don’t spend all day admiring your handiwork.

Focusing narrowly on the threat can be a viable definition of tunnel vision. It may appear that you are looking down a narrow tube at that which presents you with the most immediate danger. Your mind is telling your body to deal with this right now. The problem here is that you can stay locked into that narrow focus to the exclusion of all else.

Training yourself to avoid tunnel vision is fairly simple. It requires that you do nothing more than break eye contact with the threat and scan/assess what is going on around you. There are many schools of thought as to what the proper way is. I’ll state that I don’t believe there is a single right way to do this—but there may be some ways that are just wrong.

Possibly the original way was to slightly lower the carbine off of the sighting plain and move your upper body and weapon in unison—similar to a tank turret. The prevailing thought was that if you saw a threat you would already be lined up on it. The downside was if the threat was where your gun wasn’t.

A second common method was to keep the upper body stationary and move the head left and right. The prevailing thought here was that the weapon was in a neutral position. You were rolling the dice as to where the threat might be, but no matter where it was, you would only have to move your weapon a few degrees in order to engage.

The first method was thought of as too slow, but may well be the only method that will work when using a weapon-mounted light. You must move the gun because the light is coaxially mounted. If you keep the weapon stationary and move your head, all you will see is dark.

A method once taught by the Marine Corps Special Operations Training Groups was to lower the M4 down to the Indoor Ready—buttstock high against your shoulder, weapon rotated so it is flat against your body, and muzzle approximately 12 inches to the outside of your support side foot. They wanted the guns pointing down at about baseboard level. The problem with this is that it took a long time to get the gun up on target, especially for the Trailer Platoons who were still using M16A2/A4s—a fencepost. Retired MSgt. Joe Morrison used to comment that it looked like a bunch of guys on line whacking weeds.

There is another cute method taught wherein the shooter holds the carbine in a sort of “reverse” port arms while pirouetting 360 degrees. That you need to be aware in all planes is a given. There are, however, times when a 360 degree move may be detrimental to your health.

A great many trainers fail to understand that a method they are inexorably wedded to may not work at all for others in another vocation. Use the TTP that work best for you, and understand that the immediate situation may cause you to shift gears in order to better work the problem.

No matter what TTP you are using, make sure that in your excited state you can actually see something. Jonny Laplume says it best: “Make sure you can see what you are seeing.” He is not being trite. A great many people have a tendency to shoot the drill (for example “a pair to the chest” or “a single shot to the brain”) and then collapse.

At one school they pay lip service to assessing, and in the pistol classes you will see people zone out—get that “I am so relieved that I didn’t screw this up” look in their eyes, bring the pistol part way into the body, bend the elbows and wrist and wave the pistol around in the general direction of the target.

I have seen people who should know better do similar things with the carbine. The preoccupation with activating the mechanical safety shows strongly here, as a shooter will fire the requisite number of rounds and immediately engage the mechanical safety before assessing.

Terrific. Our guy has been trained/trained himself to get out of the fight immediately after he has fired the drill.

Not wanting to be the bearer of bad news, but the way a person reacts to ingesting bullets or frag is unique to that individual. That controlled pair, hammer pair or even NSR might not work on the particular individual whom you are processing, and that “One Shot, One Kill” nonsense printed on t-shirts and rifle range buildings can rapidly turn into something else entirely for you if you are unable to keep your head in the fight. If you manage not to die in the middle of it.

I have watched people moving down a jungle-lane type of field and engage a threat, assess and move on—and then literally trip over a target directly in front of them. They lost the bubble. Their situational awareness was at zero, and they were in the land of fat, dumb and happy.

Searching and assessing is not directed just at the bad guys. You need to know where your partner or teammates are, as well as any unknowns (whom you must consider as potential threats until you can ascertain otherwise). As an example, while you were busy servicing your threat, a teammate may have moved to engage another threat or to provide you with cover. You need to understand where they are in order to continue to fight efficiently.

This is all part of that situational awareness thing that people have been trying to beat into your brain since you started understanding what fighting was about. Regardless of what just happened, your absolute priority now is what will happen in the next second or two. You must keep your head in the fight. Losing that bubble can mean that you will lose your life—right there, right then.

Your inability to be cognizant of what is occurring around you may mean that, instead of enjoying the exhilaration of winning, you will become a pile of flaccid gray skin, rapidly coagulating blood and smelly urine that someone else will have to police up.

If the threat is down, follow him down with your muzzle. He may not be hit at all — he may simply have fallen or dropped down to gain a tactical advantage. Or he may be hit but not hurt sufficiently to put him out of the fight. Use only that degree of force necessary, but be prepared to continue using force if it is required.

Once he is down, don’t stay fixated on him. Understand that he is there, but break out of the tunnel vision that affects most of us while under stress.

A Post Engagement checklist may look like this:

- Finger straight, lower the gun slightly of off the sighting plain.

- Search and assess. (See what you are seeing).

- If everything is good in your little corner of the grid square, then

- Roll the carbine, look in the ejection port

- Close the dustcover

- Engage the mechanical safety

- Get your head back in the fight!

We roll the gun and look inside the ejection port when the tactical situation permits (read: after the immediate danger is over). You are looking to see if there is an ongoing problem—a malfunction, for example.

I have a picture book that I bring to classes. In it I have images of problems in previous classes—strange malfunctions, broken bolts from the lower tier manufacturers and so forth. I also have images of guys standing on line or in the shoot house with a visibly malfunctioned gun, no magazine in the well and the like.

In a training environment, it is only embarrassing. In the real world, it could be terminal for you and those you are with. Look in the ejection port.

Once you have looked and are sure that all is well inside there, close the dust cover. There is no viable reason to leave that puppy open if the tactical situation permits. Closing it keeps dust, dirt, flying vectors and other assorted bad things from nesting on your bolt carrier assembly.

Go back to the Jonny quote earlier. “Make sure that you can see what you are seeing.” I have watched people who should know better close the dust cover without looking right on top of a Type 3 malfunction.

Guess what, gents? If you have a bad day because you have a malfunction, it is nowhere near as bad as it is going to get when you eventually find out that you never noticed it until some smelly guys in robes are slinging lead your way. Maintain situational awareness. Don’t lose the bubble.

A number of years ago, Lt. Col. Jeff Cooper wrote what has become the handbook for mindset—Principles of Personal Defense. This small (44 pages) book covers what you need to know. The writing style is pure Jeff, and they are truly words to live by.

Regardless of what the fat lady wearing a helmet with horns and an iron brassiere does, the fight is not over until the fight is over. Don’t be in a hurry to take yourself out of the fight. Speed holstering may be very cool in action shooting games, but very uncool in a fight. Maintain situational awareness, and be prepared for the unexpected.

It is not about shooting. It is about fighting. Keep your head in the fight.

[Pat Rogers is a retired Chief Warrant Officer of Marines and a retired NYPD Sergeant. Pat is the owner of E.A.G. Inc., which provides services to various governmental organizations. He can be reached at [email protected]]

SOURCES:

David Grossman

www.killology.com

Principles of Personal Defense by Jeff Cooper