IN high-end racing, cost is no object in maximizing performance. Some racing engines cost in excess of $15 million; the horsepower-to-weight ratio reigns supreme. Expensive components made so light they must be replaced each race are acceptable.

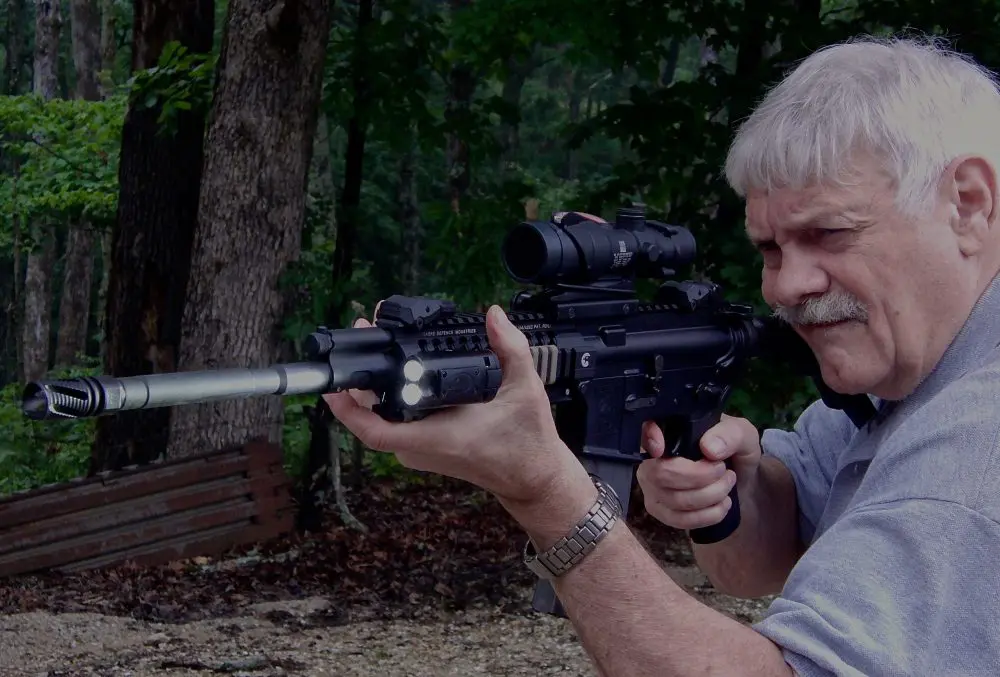

With 5.56 as a horsepower constant, I wanted to see how light I could go on an AR-15 within budgetary reason, say, under $5 million. Using aftermarket offerings, some made specifically with weight reduction in mind, safety and reliability could not be compromised. Accuracy and durability would be somewhat negotiable.

Table of Contents

THE FOUNDATION: ROBAR AND GREEN MOUNTAIN

The foundation would be injection-molded upper and lower receivers from The ROBAR Companies and a finned barrel from Green Mountain Barrels.

Various attempts have been made at plastic AR-15s, none of which have proved equal to the original design, much less superior. With aluminum inserts molded in at stress and wear points, such as fire-control pin holes and buffer tube threads, ROBAR’s effort goes further than earlier attempts. On the upper, barrel nut threads and takedown pin holes are molded-in aluminum pieces. Weight savings versus a standard receiver set is just over a quarter pound.

I did say plastic, not polymer, which means plastic. I didn’t say lightweight, space-age composite, which usually means plastic. After a few decades in plastic injection molding and mold-making, I see no reason for obfuscating the word. In that phase of my career, I participated in many defense-related programs, from submarine detection components to the SMAW-D rocket launcher. Calling it “plastic” is not really a slight.

The Green Mountain barrel’s cooling fins have lightened this 16-inch nitrided 1:7 twist barrel by 2.5 ounces. As with most nitrided barrels I have used, it needed brushing and patching before use, as the nitriding process leaves residue in the bore that should come out before firing. The flip side is that my several nitrided barrels are easier to clean.

I’ve had excellent accuracy from Green Mountain barrels, but with it anchored in a molded receiver, wouldn’t accuracy suffer, what with the critical conjoining of two important elements—barrel and sight—being plastic, not metal?

Various proven tight-grouping loads gave 100-yard groups from 11/8 to 2 inches. Tighter groups would doubtless result from using a target-scoped standard upper, but the goals here were Patrol Rifle-level functionality and light weight, not the Galactic Bench-Rest Championship. My zero seemed to shift a bit from session to session, but not enough to be of great concern—maybe two inches at 100 yards. Was it the plastic upper? Not sure. Some day-to-day zero shift has been a frustrating standard experience with just about anything.

ACCESSORIES

One might think the biggest advantage of a lightweight gun is having, well, a not-heavy gun. But what about the ability to add more “stuff” and come back up to a “standard” weight? The accessories I chose, things I feel a carbine needs, were selected with their weight being an important factor.

SureFire XC1 Light: Yes, it’s marketed toward pistol use, but it weighs so little (two-ounce savings over the four-ounce Insight MX3). It takes a single AAA battery and enabled after-dark hits on paper plates to the max range I attempted, 65 yards. Its compactness allowed no-interference mounting in the 12 o’clock position. Its beam is more floodlight than spotlight, enabling a big-picture visual input of what’s going on around you.

SOB (Sheriff of Baghdad) Tactical Sling: I originally bought this for its quick adjustability, but it is also light. The webbing itself is thinner, and hardware is plastic except for the steel hook, which I immediately cut off for being heavy and noisy. This sling won’t double as a tow strap, but it is adequate-plus for suspending a rifle in hard use. Some slings feel like sandpaper on the neck, but the SOB’s material is smooth. I rigged it front and rear with paracord as I have done with hundreds of rifles. The perfectionist in me used to hate such field-expedient measures, but done right this is a quick, quiet, lightweight, and broadly applicable solution.

V7 Weapons Systems: When a lightweight unit is the goal, look at lightweight components. I found a surprising selection of lightweight parts at V7 Weapons Systems: dustcover and dustcover rod, receiver end plate and castle nut, front and rear takedown pins made from aluminum. Also a titanium pistol-grip screw, buffer retainer, and selector. If you can save an ounce 16 times, you’ve saved a pound!

Magpul Offset Flip-Up Sights: I ordered these thinking they were plastic like other Magpul sights, but they are steel. I kept them on the gun because the offset feature works well with a scope mounted. Compared to plastic Magpul sights, I gained less than an ounce. They are robust and more easily adjusted than most.

Magpul D60 Drum Magazine: Few would dispute “more ammo is better.” One of the best reasons for lighter gear is to be able to bring more ammo for the same overall weight. This carbine as used in class, with the D60 magazine loaded to 60 rounds, weighs half a pound less than my last year’s training carbine with a magazine of 28 rounds. I’ve used every drum-type mag made for the AR, and this one makes the most sense. It’s no longer than a standard 30 rounder and the drum width is reasonable. It functioned perfectly, with lock-back, in ten 60-to-empty uses.

AIM Skeletonized Carrier: I normally would not consider a lightweight bolt carrier. But a bolt carrier is pretty heavy, so I got a lightweight one from AIM Surplus, now offering a line of AR parts. As its lighter weight might speed up the cycle, I wanted to be able to dial the gas down to compensate for it. This combo of less reciprocating mass and tuning the gas system to a particular load is common in competition ARs, offering a faster, lighter cycle. In my opinion, it is not appropriate outside of competition or experimentation.

POF Dictator Adjustable Gas Block: I would be firing suppressed at times, where reducing the gas flow is beneficial. For this I used the Dictator system from Patriot Ordnance Factory, which features an adjustment knob mounted to the front of the gas block. The knob is deeply serrated and has nine positively detented settings. Although rather small, it can be turned by hand when clean and lubed. This naturally gets harder after some use, but included with each Dictator is a special wrench. It will seldom be there when needed, so POF thoughtfully made it also adjustable with a 3/32 hex key—which will also be orbiting Pluto when needed. They cleverly included screwdriver slots. You won’t have that either, but hallelujah, the rim of a cartridge case works just fine! One downside to having gas adjustment located on the gas block is that adjustment is difficult unless the forend terminates behind the gas block, allowing access to the adjustment feature. I prefer long forends that completely cover the gas block and extend almost to the end of the barrel.

Fortis QD Forend: As fortune would have it, before I found the Dictator, I selected a forend from Fortis that is quick detachable. I chose it because it looked lightweight, but I could not think of a scenario where I would utilize the quick-detach feature until the need arose to access the Dictator. Like most forends, the Fortis is designed with a low-profile gas block in mind. The Fortis works with most gas blocks and the Dictator works with many forends, but this exact combo had only about 1/32-inch clearance between them. I was concerned about barrel-whip contact between them during firing, so I “cheated” a little and milled more clearance through the top of the rail. I can remove the forend, adjust the gas setting, and replace the forend in about three seconds. I settled on using only two positions: wide open, or three clicks open. To adjust gas, I use a cartridge rim to turn the knob if it is too hot or sticky to turn by hand. To remove the Fortis, push the lever’s locking latch, pull the lever down, and remove the forend. At first it crept forward 1/32 inch after a few hundred rounds were fired, but after tightening the lever’s clamp screw to slightly beyond the recommended torque, it held.

OPTICS

My two optics choices were made considering weight to a degree, but I was also anxious to test the new Leupold Carbine Optic (LCO), and to acquaint myself with the Vortex brand via the 1-6X Strike Eagle.

I’d been curious as to what niche Vortex is in, and found they are in them all, from affordable entry-level glass to high-end optics and accessories. If you look at what top competitors are using in events like the Precision Rifle Series, Vortex is ubiquitous.

Vortex offers three carbine-ish scopes. I physically examined the 1-6X Razor, 1-4X Viper, and 1-6X Strike Eagle, and selected the last based on image, controls, features, size, weight, and price (under $350). The Razor appeared a better-made scope but was significantly heavier and about five times the price.

When I select glass, I am also considering the Patrol Rifle students I teach: I’m not looking for the very best available regardless of cost, nor the cheapest and quality be damned. It’s about function and value. Officers authorized to use personally owned gear need to be able to afford it and not feel the need to bring a velvet pillow for it on call-outs.

The Leupold Carbine Optic has many features that similar units do not. Only thought-wave activation could get it into play quicker than its one-touch instant on and quick, knob-twist dot-intensity adjustment. Accessible “coin-operated” adjustments for zeroing (cartridge cases work too) have positive detents. Click values of ½ inch at 100 yards and direction of impact shift are clearly indicated on the body, a most useful feature so seldom seen. It’s like an EOTech and an Aimpoint shared an evening in the back seat of a Chevy, resulting in offspring having the best features of both.

The LCO’s (DL123A) battery life spec is up to 1,800 hours depending on the setting and temperature. I never used it above the middle setting, so I set it there and put it in the freezer for 28 days total, intermittently mounting and using it in temps up to 98F. I used it in several classes and loaned it to students whose red dots had gone down. I often forgot to turn it off between classes, and at ten months have yet to change the battery.

ANYTHING FOR ANOTHER HALF OUNCE

Once I got rolling on assembly, a certain level of obsession emerged, and I confess to “taking measures.” The milspec buffer tube from M&A Parts got some holes drilled (- .6 ounce). The Vortex scope mount got a mild going over (-1.1 ounces). For a flash hider, I used an experimental one made from aluminum (-1.3 ounces).

CONCLUSIONS

With the optics off, this is a sub-six-pound carbine. A different pistol grip might save a quarter-ounce over the TangoDown unit used. A skinnier barrel might save another few ounces, but I was not willing to go to extremes there. A shorter rail would help.

These receivers, the entire carbine, and all its bits and pieces did everything I asked of them over a summer of Patrol Rifle classes and back-40 shooting. An exam after 1,500 rounds showed they were holding up well.

Do I think every AR-15 should be made this way? Absolutely not. If I were tasked with equipping an agency with 50 AR-15s, they would be boringly standard.

An AR built this way puts light weight above long-term durability and the ability to take extreme hard knocks—but is tempting for some applications.