Semi-auto 7.62s. Everyone wants one, but do they represent a trend or a capability?

The past seven years or so have seen a strong trend toward 7.62x51mm (.308 Winchester) semiautomatic rifles. Each service has dabbled in a handful of platforms, several federal agencies are issuing them in decent numbers, and the market response has been strong.

Most shooters want one and many are convinced they need one. I’m here to throw a mildly wet blanket onto the idea and help sort tactical trendiness from actual capability.

Table of Contents

I NEED A 7.62!

Over the past couple of years, I’ve studiously hit every shooter I respect as both experienced and knowledgeable with a question: Given a choice between standard “ball” 7.62 such as the classic 147-grain FMJ and a 5.56 round of your choosing, what do you pick? None has chosen 7.62 yet and I’d be shocked if any did. Minus a great-performing projectile, the .308 often underperforms the hype.

When I dig further into which 5.56 load would be the choice, several often pop up: the newer GMX loads from Hornady or Black Hills, TSX loads, Black Hills 77-grain Tipped Match Kings (TMKs), “Brown Tip,” and occasionally a bonded softpoint make the cut.

Strong suit of 7.62 is versatility in load selection. Top to bottom: 180-grain Black Hills Accubond, 155-grain Black Hills AMAX, and 110-grain Hornady TAP, alongside their ballistic gel penetration.

The latest generation of 5.56 loads pushes the carbine into pretty respectable terminal and barrier performance unimagined 15 years ago. Meanwhile, .30-caliber ball isn’t a standout choice for much of anything.

Once you open the aperture to the full buffet of .308 options, the story changes. There is a load appropriate to most any task that you can shoulder a rifle for. But this is one of those areas where many options can lead to misalignment of selection and mission. A 110-grain TAP Urban might be a great choice in an open-air scenario with a sniper engaging a target amongst friendlies. The recovered weight tends to be dust, and overpenetration is unlikely.

That is fantastic unless penetration is what is needed. At the other end, a Black Hills 180-grain Accubond drills straight through intermediate barriers of about any type and still delivers messy jello and extreme penetration. That could be perfect or tragically ill-suited, depending on the mission. Most department loads walk the middle ground, with loads such as Black Hills 155-grain AMAX that balance expansion and penetration.

As I quiz folks on the universal scenario .30-cal load choice, most tend to pick the middle-ground rounds, with 155- and 168-grain AMAX popular choices. The FBI was undoubtedly thinking similarly with its choice of 150-grain Core-Lokt. Perhaps noteworthy is that the touted heavy match rounds that military snipers have experience with and an affinity for are rarely a first pick for short-barreled autos in a general role.

LaRue PredatAR in action. Lightest .30s such as this have the best chance of working in a multi-role fashion that tilts to patrol rather than precision.

THE MYTH OF FLAT

I’ve heard any number of Afghanistan vets who embraced the 7.62 extoll the virtues of their flat-shooting SCAR Heavies or short-barreled M110 or MK 11. That is a strong perception, and the only problem is that it just ain’t so.

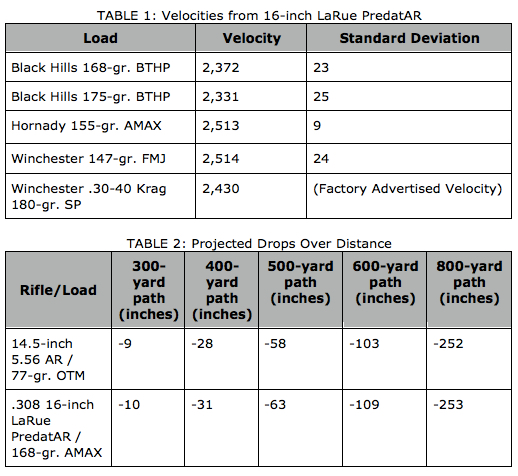

Boxcars of otherwise savvy shooters conflate data and confer “sniper rifle,” i.e., 24-inch barrel, ballistics and drops onto their 14.5- or 16-inch gun. The short barrel drops a lot of steam off of the bullet. Table 1 shows velocities of some common high-performance rounds from a 16-inch LaRue PredatAR at the muzzle.

The shorties tend to take a .308 and turn it into a .30-40 Krag, the Spanish American War cartridge that was criticized for not shooting flat enough. Table 2 shows the data pulled from a smartphone ballistic calculator comparing the projected drops of a 14.5-inch 5.56 AR launching the common 77-grain Open Tip Match with the PredatAR pushing the popular 168-grain AMAX.

The drops are essentially identical, the minor difference hiding inside the margin of error inherent with even a one MOA rifle. Wind drift is another story, and the .30-cal gas guns do provide an edge on bucking the wind. I’ve just never heard an operator point to that as the selling point. It’s usually the flatness.

Guys I respect have been very attached to their semi-auto 7.62 battle rifles. My conjecture is that at the time in question, the 7.62 gun was a better system: it had good glass on it, a bipod, a better trigger, and was a little heavier and thus typically shot supported.

Designated Marksmen (DMs) and snipers carrying these guns also tend to be much more discerning about their data and zeros. Compared to a beat-up M4 with a “good enough” 36- or 50-yard zero on its red dot, the 7.62 does allow better hits at distance, but not necessarily because of the cartridge unless the wind was full value.

Brit LMT with its issue six-power ACOG on patrol halt in Afghanistan. As pictured, marksman’s rifle dresses out at about 14.5 pounds.

DEAD WEIGHT

The weight I just detailed as an advantage in supported shots is no free lunch when it comes time to hump the rifle around and run it from the shoulder. I was involved in some of the early testing of the SCAR Heavy, and it is among the lighter .30s out there in any numbers. But once it gets a filled magazine and the typical optics and accessories installed, it lives up to its name.

The British Army LMT is an ungainly hoss that discourages offhand use. The M110 is not much better. Most of the 7.62 autos wind up in the “Whoa, this is heavy!” 12- to 15-pound range by the time they get ammo and all their optics and accessories strapped on.

The saying is, “strong men, armed” and they need to be strong with many of the 7.62 guns out there. As a rifle crosses the 8.5-pound mark, unsupported performance begins to drop, and as it gets over ten, performance plummets. We’re not talking 200-yard offhand slow fire steadied with a lead-filled 12- to 14-pound match gun, but the “winded, tired, and need to snap shoot a fleeting target hustling an RPG into position” kind of shot.

A chunk of prospective auto buyers might be better served with a practical .308 bolt gun and spending the substantial savings on ammo, training, and a standard AR.

The heavy system weight of the 7.62 battle rifles is perhaps the primary counterpoint to the upside of enhanced terminal and barrier performance with the right ammo. One close friend, a federal agent who has been issued a 7.62, relayed to me that he thought the weight issue cancelled out the .308 goodness for most of the non-gun-guy types compared to the easy shootability of an M4.

A direct correlation exists between how much a veteran likes the .308 and how far and often he had to lug it around. The vehicle-borne and short-patrol guys probably have much kinder feelings than the up-and-over-the-mountain sort. The recurring exchange I hear from individuals who have tried one of the better .30s is enthusiasm for how it shot, followed by concern and regret over how heavy it was.

HITTING

Some of the best long-range shots in the less than .300 Win Mag class that I have personal knowledge of came from great special operation shooters and issue 7.62 gas guns. One benchmark example was two SEAL snipers taking the Taliban driver and passenger off a moving motorbike at 800 yards. A bolt gun couldn’t have done it any better than their SR-25/MK 11s did. The gas guns tend to give up a little in pure mechanical precision relative to the bolt gun, but the difference can hide inside the margin of error.

However, I have seen a decent sample of shooters in advanced sniper courses transition from their bolt gun to the auto and there is often a dip in performance. I’ve seen plenty of solid bolt-gun shooters blame the auto as the culprit only to have another shooter or instructor lie down behind it and knot up a sub-minute group.

Most of the .30 autos are at their best prone in a Designated Marksman role.

Many shooters do their best work with the bolt gun and have to train harder to get the best level of hit out of the gas gun. Some shooters may actually shoot the auto as well as the bolt gun or better, but that isn’t typical. When that occurs, the bolt gun likely had a poor stock fit or lawyer trigger.

When the scenario moves into rapid multiple-target engagement inside 600 yards, the auto tends to win across the class. Occasionally a long-time sniper can run a bolt like a thing of beauty and can hold with the autos, but not often. Of course in any running scenario with movement and standing snapshots, the auto’s ergonomics tend to skunk the typical precision bolt gun.

OUTLAY AND UPKEEP

As a friend with experience fielding a 7.62 program told me, “7.62 autos are an expensive and frustrating rabbit hole.” Agencies need deep pockets to pull it off successfully because the top-shelf rifles are shockingly expensive, the right optics to take advantage of the system are just as bad, the ammo is steep, etc.

If you look at the rifles that have successfully competed in government trials and been selected and fielded, such as the Knight’s M110, FN SCAR 17, HK 417, and LaRue OBR/PredatOBR, you will see costs ranging from high to “seriously?”

Yes, the big-box sporting goods store has a rifle that looks similar and costs half the entry price, but it is a different animal made for the occasional hobby shooter or hunter.

Even the professional guns that cost an arm and a leg struggle to balance reliability, durability, and accuracy to a degree that a high-end 5.56 AR can without quibble. Just about all the major-program 7.62 semis have some experienced and vocal detractors who have seen some guns not live up to expectations. I tend to view them as semi-custom precision machinery. They must be lubricated, maintained, and treated much more like a tight custom 1911 than casually cared for in the Glock or AK mode.

Shortened M110 is a serious tool in a solid shooter’s hands, but the system weight with all the associated “stuff” challenges most to run it well off of the ground.

Parts tend to be a dedicated proposition for the semi-auto big gun, unlike the standard AR, whose parts can be had at just about any local shop and in a sea of online options. None of the high-end 7.62 makers has a reputation for ready and user-friendly availability of parts. If you stray to the broader end of the 7.62 market, there is no common “standard” and makers have been known to tweak their individual proprietary designs as they go. You may get plug-and-play replacement fit and you may not.

For those who need the capabilities and flexibility of a 7.62 repeater, the “get what you pay for” adage applies. For those who occasionally need full-power precision and barrier capability, economical choices are emerging in the mid-price light sniper/tactical bolt gun market.

It is not difficult to spec out a solid 5.56 patrol rifle and a quality bolt .308 for less than most of the top-tier autos. The savings accrue as training ammo is procured. Some shooters may be better off on both ends—a patrol rifle that handles 95% of problems and that they shoot well, and a bolt gun that covers the 5% exceptions that they can grab and shoot even better. The two-gun solution isn’t as workable on the military side of things, hence the emergence of the precision .30-cal auto.

PARTY POOPER

I realize that bucking trends is a buzz kill. Everyone wants in on the latest tactical fad. There are factors that fuel the trend and make it attractive. Due to increased demand, .308 blasting ammo is now available at prices that rival the glory days of NATO surplus as countries transitioned to 5.56.

It is still the equivalent of two quarters flying out of the ejection port rather than fired brass, but better than gold dollars. The parallel developments of 1-6X/1-8X and the 3-18X riflescopes have really helped the .30-cal auto explore its full potential for flexibility.

M14-based EBR and similar rifles were a stopgap effort that was popular for a couple of years until current-issue 7.62s were fielded. It was an awkwardly balanced collection of sharp edges and snag points.

New rifle models seem to come to market quarterly at every price point, many with attractive features. I understand the interest. As a shooter, I welcome the developments and appreciate the trend. I simply want to provide counterpoints to help those on the fence think through the risk/reward calculus.

The .308 auto is a great fit for three types of guys, as long as they understand the downsides and make good choices:

- The serious shooter who wants AR ergonomics and accessory crossover in a .30-cal platform for hunting or long-range shooting. This part of the market winds up pretty satisfied.

- The ranch rifle kind of guy who wants a semi-auto “just in case” but wants to be able to hunt with it if he chooses. This guy tends not to have a safe full of ARs and this is his one splurge.

- The professional who needs the terminal and barrier performance and will use the rifle primarily in Marksman mode but may need some “walking around” patrol capability. The lightest, best-quality rifles tend to make the happiest customers here.

Outfits that try to make every patrol rifle a heavy DM platform have sacrificed primary performance for potential secondary capability. In numerous venues, I have seen shooters tackle carbine-type training or scenarios with the top-shelf .308s.

Broadly, the times and scores of the better shooters with the .308s tend to overlay the average-skill shooters with the M4. The average shooter with the big gun tends to “bump down” and overlay the bottom of the class 5.56 shooter. In cases where the rifle is one of the even heavier models or has dedicated long-range glass, the negative effect is magnified.

For those who carefully choose to go the 7.62 route, the primary question to answer is: Is this a “walking around” or “laying down” gun? The answer should drive the rifle weight, optic, accessories, and to some degree the bullet selected.

Too often the folks doing the selecting envision a patrol rifle, then spec out a sniper system (or the reverse). It’s possible to split the difference and come out well, but that typically requires a truly high-level shooter (and the training and resources to make and maintain his skills).

If you’re thinking about a .30 auto, don’t let me talk you out of it. Choose wisely and be honest about your needs, and you may well escape getting trend-burn.

Justin Dyal retired from the U.S. Marines as a Lt. Colonel with worldwide experience in specialized units. He has taught and been responsible for numerous advanced skills and weapons courses within multiple organizations.