The Glock 19, Colt 1911 and Kahr P9 were used in the tests to represent the three common magazine widths used for defensive purposes.

It has been called a number of things: the Tactical Reload, Select Reload or the Reload with Retention. Call it what you want, but for whatever reason, a person involved in a gunfight has fired a few rounds and has decided they have time to reload.

Since the shooter has no idea how long the encounter may last or how much ammunition will be needed to bring the hostilities to a conclusion, they decide to retain the partially spent magazine for possible use at a later time. After all, it has some ammunition in it. Since it has been decided that the magazine and its contents are valuable and worth retaining, it is important not to drop it on the ground where it could bounce, slide out of reach, or worse yet, due to impact, spill its contents out on the ground or have the retained ammunition reverse direction inside the magazine. Reverse order in the magazine would eliminate the ability of the round to chamber into the weapon rendering it useless. Rounds that spit out of the magazine are also useless as they are no longer available to the shooter in a rapid fashion. In addition, the sound of the magazine hitting the floor could reveal the shooter’s location to his opponents—not good.

Currently, there is an ongoing debate within the firearms training community as to whether or not the Tactical Reload should even be taught. Those who champion the Reload with Retention say that no one has any idea how much ammo it will take to conclude a fight, thus it would be foolish to give up something that may very well save their life. Those who oppose the Select Reload state that it is too difficult to accomplish during the stress of a gunfight due to limited digital dexterity. Filling the fingers with multiple magazines is just too difficult when fighting for your life. After all, the training range is not the street.

The difference between double-stack and single-stack magazines is substantial.

Table of Contents

TECHNIQUES

The one thing that all involved in the debate agree upon is that the Tactical Reload is used when the shooter feels they have the time to accomplish the task. If the needed time is not available then the decision is easy—don’t do it!

There are three different ways (that I know of) to accomplish the Tactical Reload. There may be more, but I don’t know of them and it is unlikely that they are in wide use. The first is what I will call the Gunsite method. I will name each technique after the school where I learned it. This avoids the controversy of who invented each technique and seems fair.

Gunsite was, and is, the first public shooting school in the United States. To accomplish this reload technique, the shooter withdraws the new magazine from the pouch, holding it between the thumb and middle finger with the index finger pointed down the face of the magazine body, the same as if the shooter was going to execute a Speed Load. However, instead of ejecting the partially spent magazine, the hand is brought up under the pistol and the partially spent magazine is caught between the ring and pinky fingers. Some catch the magazine between the ring and middle finger but it is basically the same idea. Once the magazine well is clear, the hand is rotated so that the fresh magazine is in place and ready to be inserted.

What the author calls the Gunsite Technique utilizes the ring and pinky fingers as the receptacle of the partially spent magazine. The support hand brings the fresh magazine under the pistol. The partially spent magazine is then ejected into the support hand and is held between the pinky and ring fingers. The fresh magazine is then rotated and inserted into the gun.

The Thunder Ranch method is similar, but utilizes the greater dexterity of the thumb and index finger to retain the ejected magazine. The off hand holds the new magazine as stated above, however, once the hand is under the pistol grip, the index finger leaves the magazine face and slides down the side. This permits the thumb and index finger to hold the partially spent magazine while the hand is rotated to insert the fresh one.

The last technique I call the Pocket Technique since all that is done is to use the empty off hand to catch the partially spent magazine, place it in the waistband or pocket, move the hand to the new magazine (which is likely on the belt just above said pocket or next to where the magazine is stashed behind the waistband) and then use the same hand to perform a standard speed load insertion.

A CLOSER LOOK

On a recent trip to the range for my regular practice session, I was practicing my Tactical Reloads when it occurred to me that I should time myself from shot to shot to see how effective I was at this task. I was surprised at just how long it took me to perform this action. Since no one really knows how long a “gunfight lull” will last, being able to perform a Tactical Reload as quickly as possible is a good idea. I was not happy with the time it took to complete my reload. I decided to time the three techniques that I was familiar with and see just how fast I could complete them.

The Thunder Ranch Technique begins the same way as the Gunsite method. The difference is that the partially spent magazine is caught between the more dexterous thumb and index fingers.

I used a Porta-Target, reduced-size, high-power steel target placed twenty feet from my shooting position. This target is basically an eight-inch square steel plate that has an elevation similar to the high chest cavity of a six-foot tall human being. Shot placement is critical—not just any hit will do—so I kept the target region small. Starting from a ready position, on the buzzer of my PACT Timer, I would fire one shot, perform the tactical reload of choice and then shoot again. The time recorded was the shot to shot par time. I performed this test with three different guns; A Glock 19, a Colt Government with a Smith & Alexander magazine well attached and a Kahr P9 9mm compact.

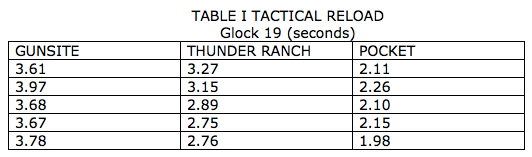

The Glock 19 is an excellent example of the compact 9mm/.40 caliber pistol that enjoys great popularity in the personal defense, law enforcement and military communities. These guns have wide, high capacity magazines and are certainly the most difficult to perform a tactical reload with unless you have large hands. Each reload was performed five times. Times for reloads are recorded in seconds (Table I).

I admit to being surprised at how much faster the Pocket Technique was over the more traditional Tactical Reloads. Depending on the category of comparison, the Pocket Technique was .5 to 1.5 seconds faster.

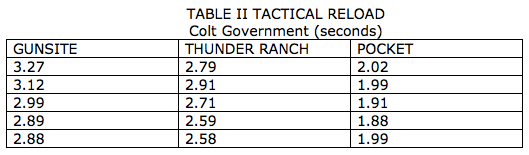

In all fairness, the Gunsite Technique was intended for use with single-column magazines like those used in 1911-style pistols. When using these magazines, the method is much easier to do.

In fairness, it should be noted that the Tactical Reload was originally intended to be used with the single column, 1911-style magazines. The test protocol was the same and the results are listed in Table II.

It is quite clear that the thinner magazine makes a big difference when trying to hold on to two magazines at the same time. The Glock magazine is much wider than the 1911 and many will say that comparing the two is not fair, however, it is reality—many people prefer the high capacity guns as greater ammo capacity makes reloading less likely. This, to me, is the greatest advantage of the high capacity gun. “Firepower” has nothing to do with it—an AC-130 Spectre Gunship has firepower—a high capacity handgun just has more ammo.

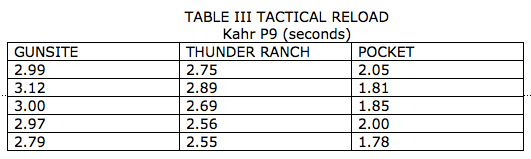

To take the “thinner is better” test a bit further in regards to the Tactical Reload, I repeated the test once more with the very thin Kahr P9 9mm pistol. The test was the same and the results are shown in Table III.

The additional thinness of the Kahr magazine really did not have much affect on the test regardless of the technique used. While it is clear that the two, one-hand techniques really work better with thinner magazines, the Thunder Ranch technique and its use of the more dexterous thumb and index finger worked better when the fatter magazines were used. The thickness of the magazine did not seem to affect the Pocket Technique one way or the other. Since the hand was empty, the thickness of the magazine was a moot point. As a matter of fact, the argument can be made that the fatter magazine offers more to hang on to, thus the technique would work better with them. The downside to this argument, however, is that the fatter magazines are more difficult to slide into a pocket as compared to the single stack magazines. I am convinced that the improvement in speed that I experienced with the Pocket Technique was that I was able to get good with it really quick.

MINIMAL TRAINING

After I completed my little test, I thought that if I put this in print, I would be criticized for not using a broader test base—and there is validity to this criticism. Practice makes perfect and the more a person practices a given technique, the better they will be at it. I am willing to bet that if I brought Giles Stock from Gunsite or Clint Smith from Thunder Ranch to perform this test that they would be able to perform their given reload technique with great skill and speed. It is also quite likely that any multiple graduate of these schools could also perform the given technique to a high level. But what about the minimally trained person who takes an occasional class and practices only a few times a year? Within this category we can place the vast majority of law enforcement officers both in this country and abroad. Most cops and agents practice with their gun when required and otherwise give it little thought. When it comes to these people, do we spend valuable training time teaching them to hold on to a partially spent magazine?

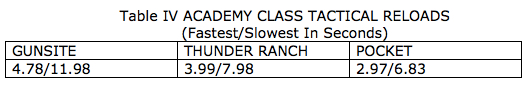

To test this concern, I used a basic police academy class that had a wide range of firearms training experience. This class of fourteen ranged from a former Marine with counter-terrorist experience to a young lady who had never held a gun in her hand before. Most fell in between with having fired a gun, but never had formal training. When I reached the point in the academy firearms program to teach reloading, I taught the group all three techniques and had them practice them for a similar period of time. I gave them no indication that I was researching their ability to perform a given technique. Listed in Table IV are the fastest and slowest times of the class. The test was the same as I performed except the cadets were shooting at twelve-inch square steel targets. It should be noted that all members of the class were using high capacity magazines with no single column versions in attendance.

Few of the class members liked using their smaller fingers to catch the magazine. While those with larger hands could perform it reasonably well, they did not favor it. In the confusion I saw several cadets actually re-insert the magazine they had just removed. On two occasions, I saw students start to drop the partially spent magazine, “snatch” on to it in order to keep from hitting the ground, which would result in the new magazine being twisted around and being inserted into the magazine well backwards. Once these students realized what they had done, they would just drop the old magazine on the ground and use the whole hand to correct the problem. This would totally nullify the entire point of the exercise.

All in the class felt better when using the thumb and index finger and learned it more quickly, but none of the cadets preferred it over simply placing the magazine in their pocket and reloading the gun. Putting the magazine into a pocket proved problematic regardless of the technique used, but all had fewer problems when the thumb, index and middle fingers were used to do so. Some found the front pocket easier, others the hip pocket, while some decided to use the waistband. It really didn’t matter to me as long as they could get the job done.

QUESTIONS

Like any new technique taught to a group of young police cadets, a number of questions followed. The first was, “Why can’t we just put the magazine back in the pouch? It would be a lot easier than trying to push it into a flat pocket.” I explained that during the turmoil and “fog” of a gunfight, that it would be possible, even likely, that the partially spent magazine would end up back in the pistol if an additional reload were executed. This would leave them back in the same position that had originally caused them to execute the Tactical Reload in the first place. Most nodded their heads until one student asked, “Well, what if you only have two magazines like a detective or off-duty officer? Why would it matter then?” The truth is, it wouldn’t!

If your spare magazine suddenly becomes the partially spent magazine that you have just switched out, then it would make a great deal of sense to put it where you could reach it easily. The bottom of a pocket would not be such a location. Am I advocating this? I’m not sure, as it may lead to an inconsistent message, but it is food for thought. It may be a moot point for many plainclothes/off-duty officers or legally armed citizens who carry no spare magazine whatsoever.

Should we stop teaching the Tactical Reload all together? I don’t think so, but I am convinced that trainers should not spend a great deal of time on it. Except for mass battlefield situations, history has shown that reloading has seldom been a factor in whether or not someone won a pistol fight. Certainly the speed load is worth teaching. If the slide locks back on your pistol then it needs to be fed and it needs it quickly! Without ammo, the pistol is nothing more than an expensive paperweight.

Should schools like Gunsite and Thunder Ranch discontinue teaching their given technique? Absolutely not! It has been my experience that a person who will spend thousands of dollars traveling to one of these schools will probably spend the time to practice the techniques taught so that they will become good at them. This attitude is a major factor in the success of any technique.

What about the minimally trained man or woman—the folks that either don’t care or only have the time and money to train at a minimal level? I will answer this with one of the questions raised by one of my academy cadets, “Dave, if putting the magazine in our pocket is easier to do, easier to learn as well as being faster to perform, then why learn the others?”

Good question.