Bullseye is the classic pistol powder and the backbone of many pet loads. We look at three classics: one each in .45 ACP, .38 Special, and 9mm.

Bullseye is one of the oldest smokeless pistol powders and still one of the most popular. Since it hit the market 103 years ago, it has been a staple for most handloaders and the backbone of most “accuracy” loads in the popular calibers. In my area, Bullseye is one of the first powders to disappear from shelves, lasting about a heartbeat longer than an econo bulk box of .22 Long Rifle ammunition.

When I finally took the plunge and started handloading (FIRST SHOTS WITH HANDLOADING: How Hard Can It Be? September 2015 S.W.A.T.), I very much wanted to start with some tried-and-true Bullseye loads, but it took an epic scavenger hunt across many months to find a canister of the elusive classic.

As I researched loads in the meantime, I kept seeing the same several popping up again and again in sources from as recent as yesterday to long out of print books from when air travel was a newfangled wonder.

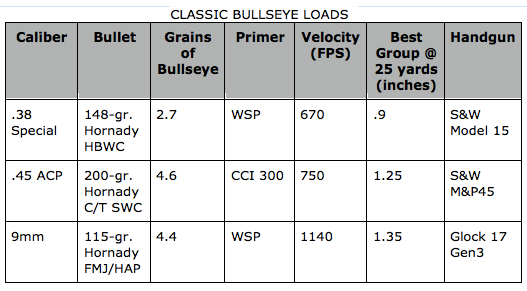

When I finally got my hands on a pound of Bullseye, I naturally started with some of these loads. Three in particular proved as good as their longstanding reputations would indicate. These were one each in .45 ACP, .38 Special, and 9mm.

Table of Contents

THE WADCUTTER LOAD

No matter where you look, the first mention in classic loads for the .38 Special is a 148-grain wadcutter over 2.7 grains of Bullseye. Through the heyday of bullseye shooting over the various match courses of fire, there was probably a Mount Rushmore-sized mountain of powder loaded and combusted 2.7 grains at a time.

This load tends to clock about 670 feet-per-second (fps) give or take 20, depending on the exact brand of wadcutter and the revolver it’s fired in. Recoil is mild enough that for many years it was the golden choice for the next introductory step for young or new shooters after rimfire.

As a young man, I came into a couple of cases of hand-me-down factory mid-range wadcutters. Initially I shot them out of my Dad’s prized Smith & Wesson 686 and learned a great deal about double-action shooting and what a truly accurate handgun can do with a wadcutter.

I soon traded off a Colt Frontier Scout .22 LR for an S&W Model 15 and happily chased all manner of small game and landfill targets with my stash of wadcutters. That blunt-ended bullet cut a clean hole all the way through whatever its modest velocity allowed it to penetrate. It is also one of the most pleasurable loads a shooter can touch off.

Classics go well together: circa 1909 S&W .38 Special and traditional 148-grain wadcutter load of 2.7 grains of Bullseye.

When I finally nabbed my own canisters of Bullseye, the first load I spun up was 2.7 grains under Hornady’s hollow-base wadcutters. In half a dozen different sixguns, it ranged from accurate to spectacular.

In a 1909 vintage Smith & Wesson target .38, the 2.7-grain load cut a nearly one-inch cluster, showing that classics go well together. In several of the guns, the old standby couldn’t quite duplicate the level of precision they exhibit with current production wadcutters from Black Hills or Winchester, but in each case, the load shot close to or right on the sights and nearly held the X ring.

My best group was .9 inch out of a Model 15. It’s worth mentioning that loaders do all kinds of obsessive rituals to squeeze the groups down. I simply took mixed brass and ran ‘em through the Hornady Lock-N-Load® AP press with the bare minimum preparation.

The mild recoil of the mid-range load is a perfect mate to the .38s that most shooters own these days—the airweight J-Frame or equivalent. Where many shooters quickly tire of even standard-pressure .38 in the little five-shooters, the wadcutter invites cylinder after cylinder of practice. This is good, because the snub takes a lot of practice to have a consistent capability.

This 1911 halved its normal so-so accuracy with 200-grain Hornady C/T SWC, shooting this nice two-inch group.

.45 “SOFTBALL”

To many shooters, .45 ACP means 230-grain “hardball” at 830 fps. That’s what the Cavalry Board asked for over a century ago, and that’s what we’ve got. But one classic target load is not far behind the .38 wadcutter in its own reputation with target shooters: a 200-grain semiwadcutter bottling up 4.6 grains of Bullseye. This load chugs downrange at 750 feet each second and functions standard recoil springs with no issue.

Coming in 30 grains lighter and 80 fps slower than hardball, as well as being lead rather than jacketed, the 200/4.6 SWC is amazingly soft. Recoil is the “good” kind that reminds the shooter handguns are serious tools but without eliciting a flinch. It’s the kind of load that will make you fall in love with the 1911 all over again!

After making a healthy pile of brass with this load, I am unlikely to ever be without a few boxes of it on standby. The load is a great learning tool in .45 for beginner and experienced alike. I wish I’d had a commercial version of this load in my ammo allocation when we were tasked with getting classes of students up to special operations standards with the issue custom 1911s.

148-grain wadcutter brings accuracy that begs the shooter to test their limits. Load cut these cards at five yards out of this Model 15.

Many of these men had no real experience with the handgun, and we had but a few weeks to get them up to very high standards that most shooters will never reach. The jump straight to relatively hot GI hardball challenged many students, and failure to meet standards meant being dropped from the course. The instructors worked magic in many cases, but having a load like this to gradually work shooters onto full-strength loads would have been a great tool.

I have experimented with both of Hornady’s 200-grain semiwadcutters in this load: the more button-nosed SWC and the longer Combat/Target (C/T) version. I favor the appearance of the C/T load and find it slightly easier to grab and orient in the loading process. Both have fed 100% in a variety of pistols and have shot very well.

A circa 1918 Colt gobbled them up, as did several other 1911s that can be particular about bullet profile. Groups with these loads ranged from 1.25 inches to just under two inches at 25 yards across a handful of pistols.

What I have found most remarkable is how well some pistols that typically fling wide groups have clustered the semiwadcutters.

Hornady 115-grain HAPs over 4.4 grains of Bullseye alongside 25-yard timed-fire target. Load shot well out of a variety of service handguns.

A GI surplus 1911 that puts most loads into dinner-plate sized groups cut 3.8 inches with the classic recipe—which is probably the only time I’ve gotten excited about an almost four-inch group! The Bullseye powder pushed five into two inches flat for another 1911 that is typically a four-inch gun. An early Les Baer .45 knotted a group of the lead SWCs into a tight 1.3-inch group, while an M&P .45 did 1.25 inches.

I can shoot this load at speeds I can’t normally reach with .45. Times across steel plate racks and many of my standard drills with the 200-grain SWCs rival my best “easy-shooting” 9mm results. Similarly on drills with set times such as firing five shots in five seconds onto a bull at ten yards, the Bullseye load allows a little more time per shot to take advantage of a great 1911 trigger and lets the shooter nearly push shots into the same hole.

This is an easy-shooting load that can cause some power-philes to tusk-tusk and comment. True enough that it doesn’t make power factor for Custom Defensive Pistol in IDPA or “major” in USPSA competition. But it’s also worth considering that it’s pushing the same size and weight projectile at the same velocity as the standard Army revolver load during the Civil War.

I’m not recommending that you carry the Bullseye load, but don’t feel as if you are going to tactical purgatory for enjoying this load, either.

9MM

Bullseye is primarily associated with .38 and .45—after all, it says right on the bottle: “Great for .38 Special and .45 Auto target loads.” But it is equally at home in high-velocity auto loads.

I’ve played with several that I like, but the classic in 9mm is 4.4 grains driving a 115-grain jacketed bullet. This load is in the general velocity bracket with most generic or bulk box 115-grain loads and zings over my chronograph at 1,125 to 1,140 fps from a Glock 17, depending on bullet style. I’ve tried full metal jacket and the Hornady Action Pistol (HAP) match hollow point in this load, and both ranged from good to great in my nines.

Depending on the drill, 200-grain .45s let shooter push faster or use available time to shoot better, with significantly less recoil than hardball.

Interestingly, I had pistols that would shoot one well and the other impressively, but have not yet had one pistol do magic with both. For example, a Glock 17 shot the HAP into 1.35 inches and the FMJ into 2.2 inches at 25 yards. I’ve not had a handgun entirely reject either load, so the recipe seems to be a worthy third alongside the previous .38 and .45.

The 9mm Bullseye load is a good stand-in for either training or match ammo, with the velocity putting the power factor comfortably over the minimum for action sports without too much extra oomph. I found it to be a nice blend of accuracy, soft recoil, and sure functioning, with enough spice behind it to reliably topple steel targets.

Each of the classic loads is also economical. I estimate that the price for each of the three loads runs between $7 and $8 per box of 50. A little shopping around might do better, as would casting the lead bullets. The quality of the loads equals a bargain.

Classic loads are economical. Components add up to far less than even generic grade factory ammo.

DOWNSIDES OF BULLSEYE

Any discussion of Bullseye is incomplete without mentioning a few of the downsides. Bullseye is a little smoky, a lot sooty, and has a distinct odor. I don’t mind it at all, though others do and look to similar performing powders that address these things.

I like the smell of Bullseye, don’t mind wiping the handguns down after a range day, and the dark soot that accumulates on my support hand when shooting wheelguns in particular just reminds me to wash up.

The more serious concern for some loaders is that the small charges of fast-burning powder take up little room in the case, making it possible to double charge a cartridge and exceed safe pressure. That isn’t unique to Bullseye, but is certainly more pronounced with the relatively small charges required. It is less of an issue on a progressive press, but still requires attention.

Wadcutters are tailor made for lightweight snubbie practice, allowing shooters to enjoy shooting the pocket guns.

The upside of the grainage is that the small charges mean more loaded rounds per pound of powder—helpful since Bullseye can take a while to reacquire once the container is empty.

I could knock out a pretty substantial chunk of my shooting needs with only these three loads. They are true classics, and I hope you get as much use out of them!

Ethan Johns is a military professional with worldwide experience in specialized units. He has taught and been responsible for numerous advanced skills and weapons courses within multiple organizations.