How do .38 and .380 hideout guns stack up against a full-size service pistol up close and fast? We put them to the test.

In a previous issue, we looked at just how far the back-up gun, or BUG, could reasonably hit from realistic positions (HUNDRED-YARD POCKET GUNS: Stretching Out The Backups, February 2014 S.W.A.T.).

The answers challenged prevailing perceptions of how far away a little hideout .38 or .380 can consistently connect with a torso-sized target. The little guys clanged steel out to 100 yards from a vehicle brace and rather well out to 60 yards from standing. The results certainly boosted my confidence that the BUGs could make the grade in an extreme situation out farther than most can picture using them.

But this raised another question. Being able to hit better and farther than expected might just be false confidence if the back-ups are lacking up close and fast, where they are more often needed. Good pistol work is a constant balancing act of speed and accuracy, so the natural extension of the project was to look at “BUG speed.”

Recovering from recoil in rapid-fire string with Ruger LCP.

Table of Contents

TEST GUNS AND AMMO

The same handguns were used as in the distance tests. The Smith & Wesson 642 Airweight J frame enhanced with Crimson Trace LG 405 Lasergrips represents the perennially favorite snubnose revolver class. For the pocket .380 class, the obvious choice is the Ruger LCP, with sales figures over the last few years that almost singlehandedly caused a two-year market-wide shortage of .380 ammo.

The two backups represent the majority of what is actually carried by concealed carry licensees. They also represent the only personal firearm for a significant slice of first-time buyers. The two handguns’ additional standing as backups and off-duty weapons for law enforcement is well cemented.

The Glock 17 was again brought in as a control. The polymer 9mm served as a baseline for the backups’ performance, since I have plenty of comparative data on the pistol. Moreover, the Glock is the most commonly issued service pistol for law enforcement and widely prevalent in home defense.

Hornady Critical Defense Ammunition was used in all three handguns. Each was fired with standard-pressure loads to keep the comparisons as meaningful as possible. The Glock ran with 115-grain FTX bullets, while the Ruger punched 90 grainers. The J frame fired 90-grain Critical Defense “Lite” ammo, which gave it as great a chance to excel as possible.

Juicing up the Smith with +P ammo is certainly possible, but the object here was to look at standard-pressure controllability.

S&W 642 Airweight with five-yard index card composite of several runs.

STARTING BLOCKS

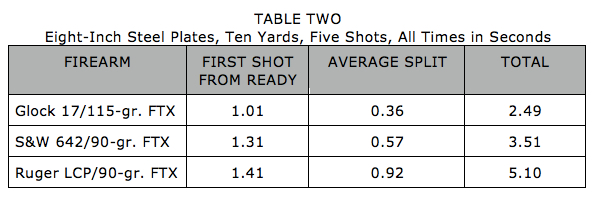

The first test is what I prefer to gauge how controllable a particular load or handgun is: firing at eight-inch steel plates at ten yards. The distance equates to many indoor scenarios as well as vehicle to vehicle in traffic stop trim. The eight-inch plate represents good center chest hits from most angles. The distance and target size are easy enough that I can reasonably expect to hit every time with proper execution, but just difficult enough that the sights must settle back from recoil well to hit the next plate.

The split time—the fraction of a second between two plates being hit—ends up being a solid numerical representation of control. The lower the split time, the better the control. Five plates were used to keep the comparisons J-frame friendly.

The control Glock knocked over steel satisfyingly fast, sounding off “ting-ting-ting-ting-ting.” The front sight would lift off of one plate and snap right back down onto the next. The realignment of the sights onto the plate and the press of the trigger were indistinguishable in sequence. It might not have been USPSA grandmaster level work, but the runs felt good. The averages tallied out at 2.49 seconds to clear all five eight-inch plates. The first plate fell at an average of just barely over one second from the ready and each remaining plate took a dive in .36-second intervals.

Swapping over to the Airweight J frame, the plates tumbled off the rack a little more slowly. The Crimson Trace Lasergrips’ extra material over the backstrap seriously helped controllability, and the lightweight Hornady loads didn’t rise too badly in the hand. The trigger on this well-worn 642 is nothing to complain about either. The extra time to stroke the double-action trigger through the cylinder rotation accounted for most of the difference, with the total to clear the plates at 3.51 seconds.

Crimson Trace Lasergrips-covered backstrap greatly helped recoil control, as did Hornady “Lite” Critical Defense loads. All strings were shot with sights and with laser off.

The DA first shot and a fraction of extra time to verify the alignment through the tight fixed sight notch put the first shot at 1.31 to the break. Transitions to the remaining plates averaged .57 second. Overall, I was pretty pleased with the snub runs. Of course, as the last plate tumbled with each run, the J was effectively out of the fight until reloaded. The few runs that I slipped a round over the plate drove this point home—misses are particularly noticeable when there is no reserve or option to clean it up.

The little LCP was up next. Recoil on the miniature auto is not at all bad, but it is so small that there is not a lot to hang on to. The double-action trigger pull is lighter than the snubnose’s at 6.5 pounds, but has a bit of travel length to negotiate while keeping the sights aligned well enough to hit a plate.

The average total for five hits was 5.1 seconds. The first shot rang steel at 1.41 second from the ready, and splits averaged .92 to get the pistol back onto target and stroke the trigger. This felt like “press…tink…press…tink” as the .380s rocked the plates over.

I wanted to go faster, but hitting with the flyweight at ten yards requires the patience to do it right. On the other hand, it was a little rewarding to clean the plate rack each time with something so small and still have two rounds to stand over the pile of plates with.

To put this in perspective, consider a shooter facing two threats standing shoulder to shoulder at ten yards, each at the ready armed with LCPs and our hero with the Glock. From a simultaneous start, the data suggests our guy could center punch both threats and be recovering the sights for cleanups while the threats are still attempting to fire. An exaggerated scenario, but context for thought.

Eight-inch plates at ten yards were used to compare BUGs at close range. Critical Defense FTXs were used in all three handguns.

15 FEET TO GET IT DONE

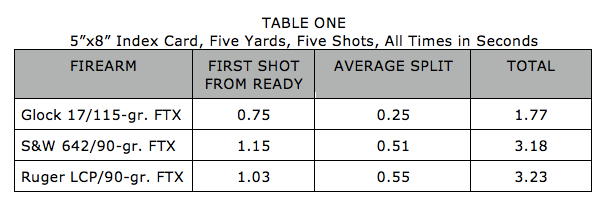

At the length of a full-size vehicle, the ability to rapidly place multiple rounds into a miscreant bent on serious bodily harm is high up on the “yes” list. The next test was to square off against a 5×8 index card at five yards for a five-round Bill-type drill. Five rounds from the ready as fast as I could make it go and impact the card, simulating a cylinder-full of fight to dominate a single threat.

The Glock 17 set the pace at 1.77 seconds total for the barrage of polymer-tipped FTXs. The first shot averaged .75 and the splits .25. I was shooting for 100% hits on the card, so had splits as low as .22, but none in the high teens like I expected. Many can easily get that fast with a service pistol. The quarter second per shot is about the tempo researchers have shown shooters to produce under duress with mixed accuracy on full value targets. The footnote here is that the quarter seconds resulted in a fist-sized group right where intended.

The Airweight cracked the first shot at 1.15 and emptied its five-shot cylinder at 3.18 seconds. The average time shot to shot was .51 to ensure the hits stayed within the 5×8 card. The J had comparatively smaller gains when compared to the other two, with just a nearly imperceptible .06 boost on the single target at half the distance.

J frame and LCP are wildly popular and convenient, but have limitations that each shooter must work through.

The lag time wasn’t so much recoil, which is certainly there in a 15-ounce revolver, but a combination of that and keeping the front sight centered while working through the double-action pull in such a small and light piece. Individual shots got down as low as .39, but most hovered right around the half-second mark. This is with mild standard-pressure fare—those stoking the J with Elmer Keith inspired rip-snorters might consider an additional tax.

Picking up the Ruger, I was able to punch out the first hit in 1.03, certainly attributable to the decent sights and lighter trigger pull relative to the J frame. The fifth shot broke at 3.23 on average. Follow-up shots took .55 second to recover the auto from its recoil and cycling and move the trigger through the arc. There’s a lot going on as the little .380 cycles and only a finger and a half of grip to use for control.

WHAT THE OTHER GUY’S DOING

Half-second splits are not particularly comforting, really opening up reactionary possibilities for the receiving party. I’m not suggesting that someone could dodge incoming rounds like a science-fiction movie character, but that the subsequent rounds are spaced just far enough apart that the likelihood of the target reacting, moving or successfully closing on or affecting the shooter in some way increases.

At quarter second or less splits, the likelihood that the shooter retains the initiative and is inside of the threat’s reaction/decision-making cycle is better—not guaranteed, but better. The challenge is that placement is critical with the less-capable rounds and limited capacity inherent with BUGs, so the time required to place the shot is the price of doing business.

The same Bill drill was shot strong hand only for data. The first shots for all three handguns broke at just over one second. The recovery time shot to shot was .58 for the 9mm, .83 for the Smith, and .99 for the LCP.

At five yards from a living enemy, .83 to .99 second is so long that follow-up shots are likely to be contact if the threat elects “fight” rather than freeze or flee. This can lead to the inevitable for many—pushing beyond established skill under stress to maximum mechanical speed and resulting loss of control over the results.

Data from support hand only showed yours truly was embarrassingly out of practice and was not consistent enough to suggest any conclusions.

Glock proved its reputation for being extremely controllable at maximum speed, setting the pace. Photo: Todd Green

RUNNING THE NUMBERS

This is where I could gamely attempt to pontificate about how one should or should not feel about carrying a small auto or J frame rather than a service pistol as a primary defensive weapon. I don’t know that doing so is useful.

Some are carrying those handguns because that’s what they have or all that they can or are willing to conceal in their situation. The data is presented in “food for thought” mode to help the good guys consider their armament and what its capabilities and, just as important, limitations are. Far too many of the warrior class simply drop a J frame/.380 into a pocket and shove off to meet the day without having truly run it hard in training to see how it stacks up.

The one thing I would suggest for those carrying the BUG is that it has limitations in capacity, power and speed/ease of employment relative to a full-size service pistol. Recognize this and commit to offset the deficiencies with determination and discipline to use it well.

Someone else’s skill level may show more or possibly less deviation between the service pistol and backup than my numbers. These numbers are a good starting point for comparison and consideration.

Your numbers are waiting for you at the range.

SOURCES:

Crimson Trace Corporation

(800) 442-2406

www.crimsontrace.com

Glock, Inc.

(770) 432-1202

www.glock.com

Hornady Mfg. Co.

(800) 338-3220

www.hornady.com

Smith & Wesson

(800) 331-0852

www.smith-wesson.com

Sturm, Ruger & Co., Inc.

(203) 259-7843

www.ruger.com