There is more to hitting than just having an “accurate” handgun.

We tend to get tunnel vision on the mechanical precision of a handgun and a given load, as if the group size at 25 yards is the singular ingredient in “accuracy.”

Accuracy isn’t like a high-end steak dinner, where the only real ingredient is cow. It is much more a stew of a number of ingredients, each ideally supporting the rest for a satisfactory result.

There are seven consistent factors in practical handgun accuracy, although some situations may introduce others. These are, in no particular order:

- Mechanical precision of the handgun and given ammo

- Visibility of the sights

- Quality of the trigger break

- Fit of the weapon to the shooter

- Range and visibility of the target

- Regulation of the sights

- Available time to make the shot

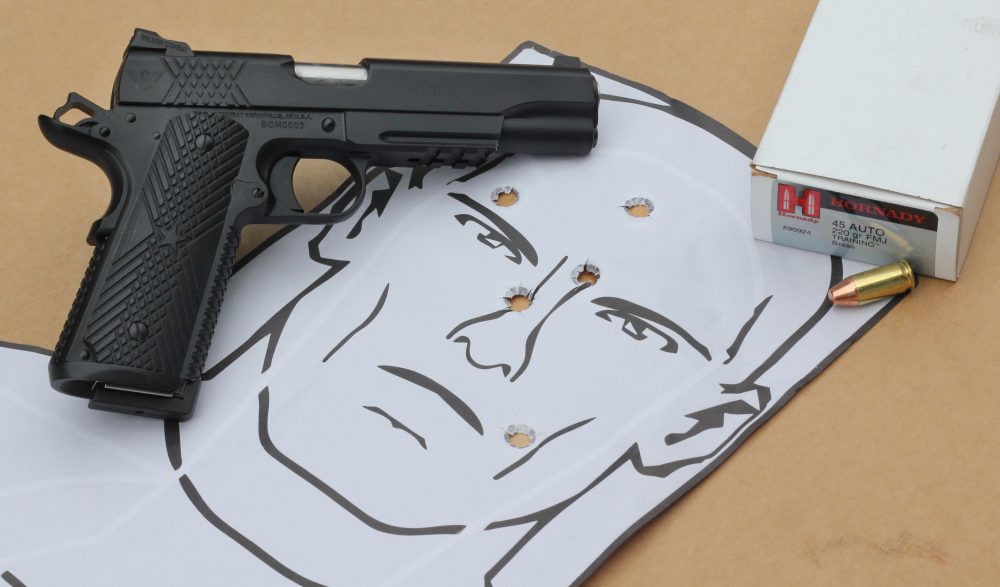

Standing head shots at 44 yards with BCM Gunfighter 1911 and Hornady Training loads. Dental shot is a called flyer from 2.5-inch group. Fit, sight and trigger quality, regulation, and precision all came together to allow on-demand hits beyond what is normally expected.

Table of Contents

CLOVERLEAFS

We all want a handgun that will cut a five-shot cloverleaf every time it is directed downrange. But what do we truly need and how hard is that to get? As a spitball figure, I estimate that most of the service and defensive handguns on the market average between 2.75 and 3.50 inches at 25 yards.

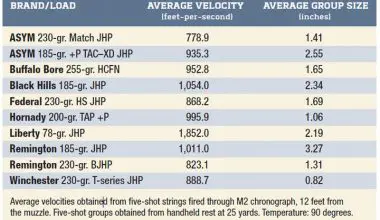

Most of those are capable of better with the right shooter on a rest and enough loads to choose from. This is where quality counts. The better defensive hollow points often shoot very well. Chances are fair that the gun will cut two inches with at least one of the good JHPs. In fact, it is not unusual for a service auto to get down closer to 1.5 inches with the good stuff.

The generic ball ammo that most shooters rely on for 99% of their practice sometimes group into as little as two inches with an occasional wonder-group. However, even in my most accurate pistols, I find the average across makers to settle around 2.5 inches for bulk ammo. That meets most training needs rather well.

I find that most production pistols fall into the 80/20 bracket: they group 80% of common loads one way (either well or poorly) and the remaining 20% the other. It is admittedly disappointing when the 80 is on the pattern-flinging side of things, but even then there are often several loads that will cluster acceptably.

Going the custom route can push the percentages in your favor, but even high-end match pistols may have a load or two that is poor by comparison. If you are shopping in the junk pile, results may be different, but among reputable makers probably 20% of loads shoot well enough, even if most are disappointing.

The occasional gun shoots everything with mediocrity, but most I see are 80/20s. This is important to understand. Recently I shot with someone in the industry who was discouraged because a match barrel from a reputable maker was not shooting up to his expectations. When I asked how many loads he had tried, it was a grand total of one. And that was remanufactured bulk ammo!

The tried-and-true approach is to try another bullet weight, another maker, or another projectile style before condemning a possible 80% tack-driver as a 100% lemon. If you are sitting on a shipping container full of a specific load, the situation and your needs may be different.

Telling on myself here, I recently discovered that a 1911 I’ve had for years and condemned as hopelessly indifferent to where it poked its rounds was actually capable of shooting. For most of the time I’ve owned it, the .45 was fed a couple of distinct loads, which it flung into 4.5 to 6 inches at 25 yards.

I considered putting a new barrel in it, so went and shot some baseline groups to do the whole “before and after” thing. Lo and behold, it shot Wilson Combat 230-grain HAP loads and Winchester Ranger 230s into 2.25 inches. 80/20 at work. Who knew?

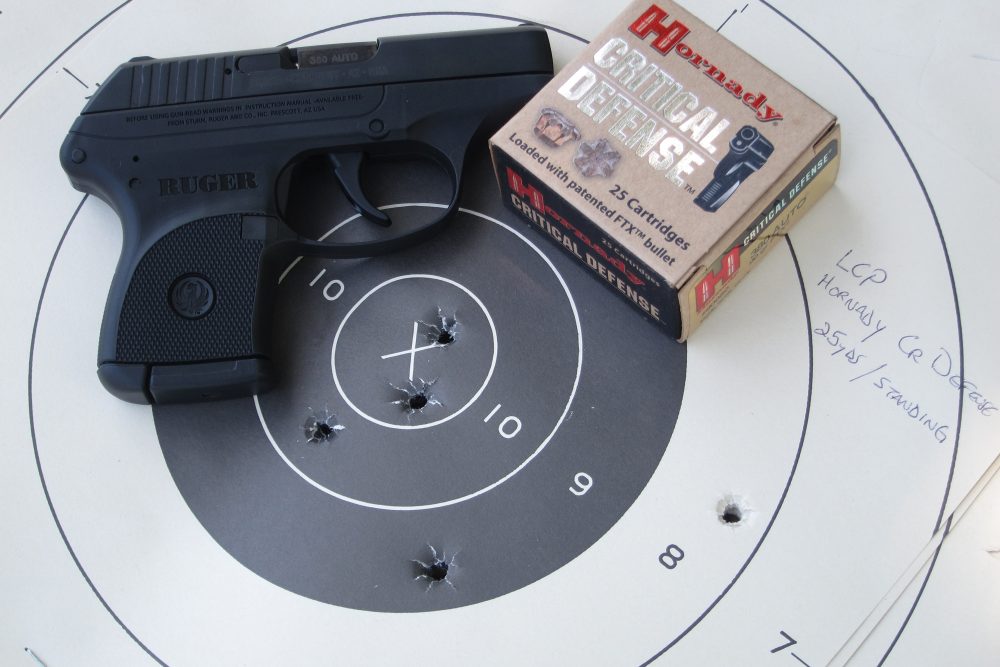

Mouse guns can shoot too, as this Ruger LCP shows, but it usually takes a lot more time and effort (and sometimes good fortune) to make it happen.

The 80/20 applies to a certain degree to ammunition as well. I’ve shot identical pistols that were polar opposites in which loads they preferred. One neared an inch with Black Hills FMJ, while its twin rejected it outright. The twin stacked Hornady Critical Defense 135-grain 9mms into a bottle cap, while the first poked DVD-sized groups with it. It is easy to fall into a pattern where you expect a certain load to deliver across all platforms, but it is counterproductive to judge a gun by a single load.

I still have loads that I reach for first, expecting great results, but I’ve accepted that a given pistol may not love the load as much as I and most of its peers do.

Groups you can cover with a thumb are obviously preferable to those you need a dinner plate to cover, but how precise is good enough? Some people relate the requirement to the skill of the user, others to the desired maximum range. Both are relevant.

In those respects, 2.5 to 3 inches at 25 yards is very useful, allowing most shooters to run out of skill before precision is the deciding factor in the hit. The typical front sight covers about three inches at 25 yards. It is very helpful to have the group fit tightly within that square so that when you place the sight, the round falls on what you cover.

As you stretch the distance or the difficulty of the shot, more precision is required to ensure hits. A 1.5-inch grouper will take almost any shooter where they need to be.

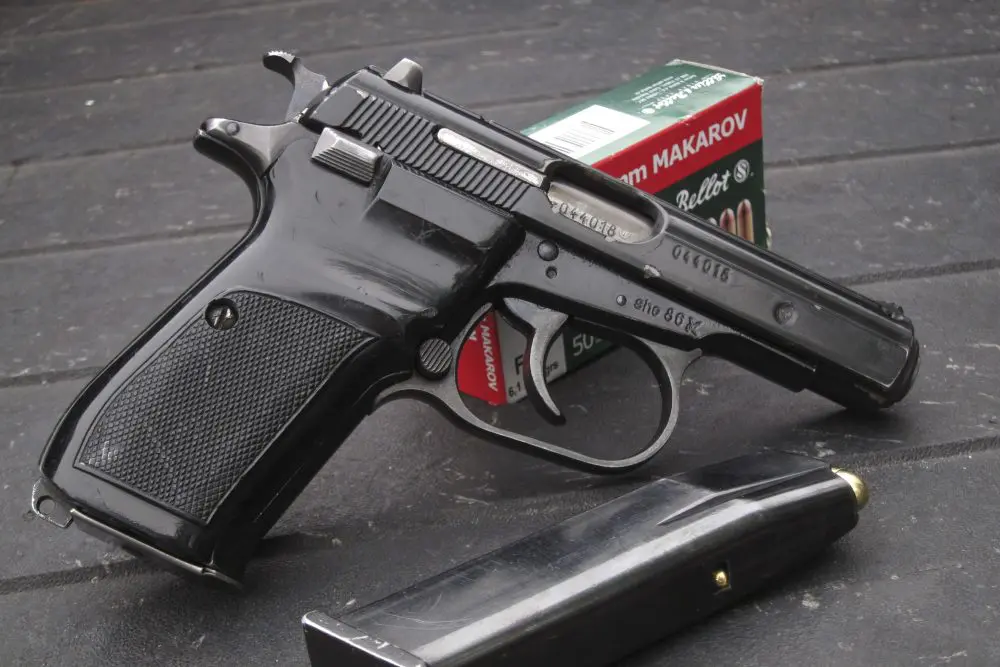

With the above laid out on the one hand, the overwhelming majority of pistols are used “for real” at distances that a cheap squirt gun is in range. Several of my more often used handguns over the years are conspicuously “imprecise.” They are quite frankly a pain when doing skills training at distance or in competition.

But it is a useful mental tether to take a short gun that curveballs a six-inch group at 25 yards and shoot it at seven yards. Generally the shot holes easily cut within a typical business card.

GI Surplus Colt with one of its better 25-yard groups using Black Hills semi-wadcutters (six-inch, chest). This still allows hits within a business card at seven yards.

HITTING VS GROUPING

Sights and trigger are the “tough shot” chant for a reason. Regardless of what a handgun does over a rest, at some point the shooter has to pick it up and hit on demand. In this arena, how well our hero is able to see the sights and cleanly break the trigger determines the hit.

A pistol I shot for some time had great Warren Tactical sights and a smith’ed trigger that broke exceptionally well. It took me a while to fully realize that the pistol didn’t group most of my ammo well. The quality of the sights and trigger allowed me to hit right up to what it could deliver, effectively masking its mediocre precision. Great sights and triggers outperform a more precise gun with lesser sights and a sub-optimal release nearly every time.

Checking loads can yield match-level combinations, as with this Glock 17 and Black Hills 124-grain FMJ.

LIKE A GLOVE

Fit of the handgun to the shooter matters. If I grip the iron differently every time, then the gun is recoiling against its “base” differently with each shot, which will result in a slightly different point of impact. That matters most for maximum precision at distance.

Up close, there is a solid chance that if the fit and resulting grip are poor, the shooter has sacrificed stability and best leverage against the trigger. This is an express ticket to snatchy-ville. Worse, if the fit and grasp are poor, the handgun gets running room to take short jabs into the meat of the mitt and quickly leads to flinching along with snatching.

If you have ever shot a J-Frame with the old skimpy wood panels, you have an idea of this phenomenon. The challenging fit, small sights, and heavy DA trigger make a proportionally greater impact on hit potential than whatever the little snub is mechanically capable of grouping.

On the other end of the spectrum lies the 1911. The Government Model fits many hands well and, if appointed with good sights and the kind of trigger it is known for, it can allow the shooter to perform at near max capability.

REGULATE!

Trailing just behind poor technique, the next leading cause of misses is poor sight regulation. In any crowd of 100 shooters, if you asked how many knew exactly where their sidearms are set to impact at 15, 25, and 40 yards, you would probably net enough to fill up the saddle of a moped.

Even experienced shooters have a hard time keeping track of the zeros on their assorted pistols and with different loads. Many service pistols are sighted to impact two to four inches high at 25 yards. Some are dead on at 25. Both of those arrangements assume a certain standard-type load for caliber. In general, heavier bullets impact higher than normal and lighter impact lower, but that is a generality, not a guarantee.

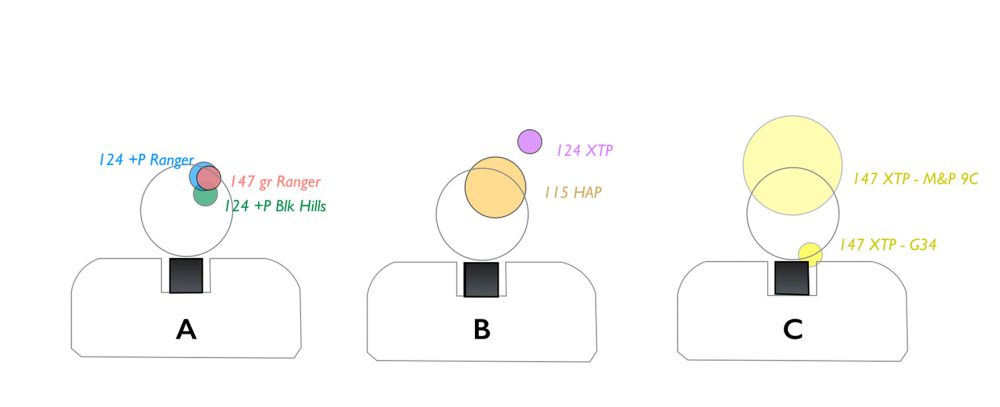

Some handguns throw each load to a slightly different point of impact, while others pile them all into a single group. In the accompanying illustration, Figure A shows an S&W M&P9c as an example that throws three of its best defensive loads, 124-grain +P Black Hills, 124-grain +P, and 147-grain Winchester Rangers into a single overlapping group at 25 yards. This is the same general point of impact as the 115-grain Hornady HAP reloads illustrated in Figure B, showing all three common 9mm weights in one group.

Sight picture with relative sizes of 25-yard bull (open circle above front sight) and groups (colored circles).

That is not necessarily typical. Figure B shows a vertical as well as lateral shift between the 115-grain Hornady Action Pistol bullets and 124-grain XTP reloads. With either of those loads, assuming you could cover a standard 25-yard bull (or tight real-world shot) with the front sight would yield a miss. The shift between loads of the same weight is usually no more than three inches at 25 yards, while bullet weights at opposite ends of the scale sometimes shift up to five inches. Either is enough to account for misses on difficult shots.

Figure C illustrates the 80/20 principle. The same 147-grain XTP reload that shot 1.3 inches out of a Glock 34 shot quite high and wide from the same M&P9c that shot the impressive groups in Figure A.

Interesting and atypical, the Glock printed the 147s two inches lower than point of impact with standard loads. That’s not supposed to happen, but goes to show how each load and weapon combo can chart its own path.

TIME

The available time for the shot is where the other factors converge. A good shooter can do solid work with dinky sights that are slightly “off” and a creepy trigger, but it takes extra time—usually a lot of it.

This is where we get off track from relying overly on slow fire shooting-around or rested groups to determine a carry gun’s accuracy potential. Slow fire doesn’t really exist except in the most casual of settings. Employment of the hand cannon is inevitably in a time-pressured environment.

Under even mild pressure between two pistols with identical rested groups, “on demand” accuracy can be radically different. Here fit, sight picture, and trigger quality meld to let a shooter get to center hits at reaction time intervals when all is well, or serve as a drag anchor when those factors lag behind acceptable.

A good shooter can absolutely make a long shot with a pocket .380—it just may not happen in the time interval required. As a gross rule of thumb, the mission-type shooter needs up to an extra .75 second to hit an eight-inch target for each additional five yards of distance.

As distance to target increases, sight regulation becomes increasingly important. It took a few adjustments and the right load to get this G34 to ping steel at 120 yards.

TARGET

Often overlooked is the quality of the target itself. Good accuracy requires a good target. A custom masterpiece shooting one-inch groups may not get it done when the target is indistinct, poorly lit, and fades out when you lock onto the front sight.

I find that for rested precision, a square target just a little smaller than the front sight produces the best results. For timed accuracy drills from standing, most shooters benefit from a classic bullseye that is large enough to give a distinct aiming point as well as allow some of the natural wobble and drift that is visible in the sights at distance without scaring the shooter into jerking the trigger.

Visual acuity and skill level determine if the classic 5.5-inch B8 center or an eight-inch bull gives the better standing sight picture for practice at distance.

BOTTOM LINE

The takeaway is that there is more to hitting than simply having a precise tool, despite the focus of most reviews. Across the spectrum of accuracy factors, the shot dictates which are the most important at that time. But you can get a solid leg up by determining which load shoots acceptably and drifting the sights to that.

Next, dry fire the snot out of the pistol to learn the trigger. Then the hard part is the discipline to break the shot.

Ethan Johns is a military professional with worldwide experience in specialized units. He has taught and been responsible for numerous advanced skills and weapons courses within multiple organizations.

SOURCES

BLACK HILLS AMMUNITION

(605) 348-5150

www.black-hills.com

BRAVO COMPANY MFG.

(877) 272-8626

www.bravocompanymfg.com

HORNADY MFG. CO.

(800) 338-3220

www.hornady.com

WILSON COMBAT

(800) 955-4856

www.wilsoncombat.com