Soldiering, law enforcement and other alpha-male professions take a toll on the body.

Even without any fight-related injury, aggressive training and physical conditioning may result in some temporary loss of function and recuperative time loss. Likewise, accumulated mileage or wear and tear can lead to joint and back issues while still on the job or in the future.

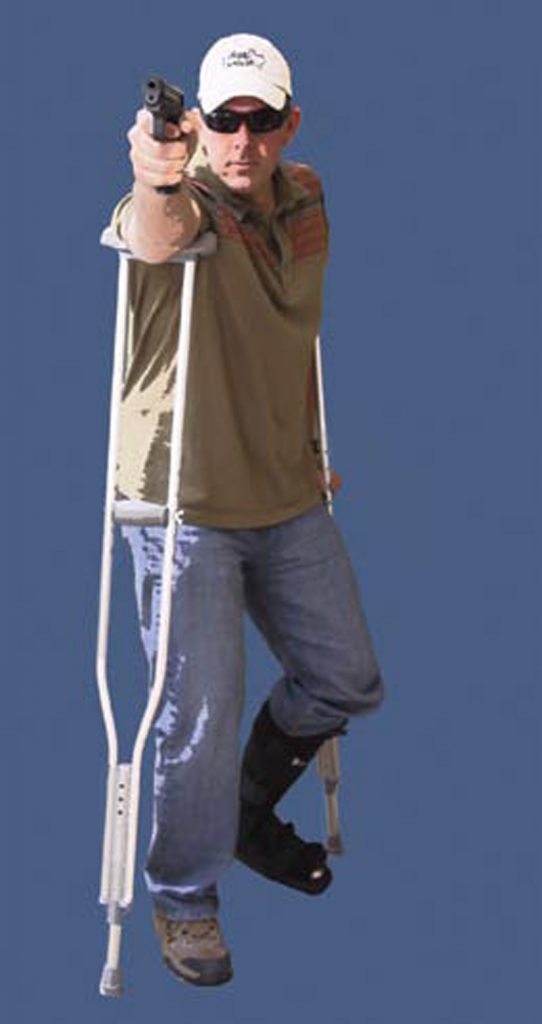

I recently had the opportunity to consider some of these issues while recuperating from job-related ankle surgery. A number of things occurred to me after I was already crutched up that may be appropriate to consider prior to injury or scheduled medical treatment.

Table of Contents

CONSIDERATIONS

Many of the assumptions and choices that frame one’s combat mindset may no longer be wise following an injury or medical procedure. Many of these are influenced by an individual’s normal or, for wishful thinkers, ideal physical capabilities. Without a careful re-evaluation, a shooter may enter an injured or rehabilitative phase operating under poor choices and assumptions that were meant for a different physical condition.

Some areas that must be considered are target posture/vulnerability, escalation of force options, deadly force criteria, weapon selection, carry and employment methods, and back-up options.

TARGET POSTURE

Even though most people do not actively think about it, many mindset and use of force decisions flow from an individual’s personal vulnerability assessment. If one lives/works in a low crime area and is generally as or more physically able than many of the potential threats he encounters, it colors decision-making. Likewise, the aging man in a crime-ridden area with an aggressive gang presence of young males is influenced by these factors and behaves accordingly.

Once the individual’s physical capabilities are changed, he probably presents a different target; slightly less so in the first scenario, while the infirm looks a lot more like food in the second.

Anyone who has spent time on crutches or wheelchair-bound can tell you that the way others perceive you shifts, and the primeval pecking order is changed. Predators of every species appreciate the easy hunt that the injured present, and this must be consciously considered when one of society’s guardians is injured and out in the ‘Ville, especially among those who are used to being deferred to by virtue of physical size, position, etc.

ESCALATION OF FORCE OPTIONS

When I am out and about, my personal escalation of force options in my generally low-threat environment rely heavily upon posture and voice, followed by different levels of combative physical force. I generally do not maintain a less lethal tool other than a flashlight.

Within that escalation, my normal hierarchy maintains the options to avoid, disengage or run at any level. Once injured and reliant on crutches, I realized that both posturing and physical options were nearly removed from the table, while the ability to run was laughable.

This places a strong burden on the ability to avoid and has caused me to reconsider appropriate less lethal options for my exact situation. Without this realization and adjustment, it would be very easy for a normal strapping SWATtype guy to quickly get in over his head while injured. Standing on one crutch trying to beat someone with the other is either going to be comedy or tragedy.

DEADLY FORCE CRITERIA

I’m no lawyer, but as the physical capacity to defend oneself decreases (as discussed above), the threshold for employing deadly force may shift. This is a tremendously important point to consider carefully before a situation may arise. Whereas the threshold for a six-foot-plus American fighting man may be pretty high before he can realistically claim to be in fear of life or severe bodily harm, that same individual with a significant injury or immobile limb may be in a different boat.

WEAPON SELECTION

The weapon carried for self-defense needs to support the preceding considerations. Once injured, I realized that my normal choice was less than ideal. I typically carry a five-shot revolver, chosen deliberately based upon my ability to shoot it very precisely despite it being a challenging weapon. The snub’s capacity limitations were a minor point to me because I was willing to incorporate the .38 into a physical attack or use it to break contact.

Once my mobility changed, the limitations inherent to the snubbie gained significance, while my ability to shoot it as well while on crutches was questionable. I decided to switch to a highcapacity compact auto—a Smith & Wesson M&P9c compact. I can shoot it slightly better, and it gives me more chances to solve the problem by gunfire before a threat can get their hands on me.

Carry mode is another important consideration. Once I decided to switch weapons, I had to determine the best way to carry it under my current circumstances. Typical behind-the-hip carry, whether IWB or on the belt, would have led to some significant printing issues when used in conjunction with the predominant forward-leaning posture under crutches. Even had I been able to resolve that issue, reaching around and behind the crutch to get to the gun was simply too awkward.

I ended up with the pistol in an appendix position up front and found it worked very well. Access to the gun and concealment were superb regardless of where the crutches were positioned.

It may be worth noting that those who might normally discount fannypack carry might find it useful while on crutches or in a wheelchair, both for ready access as well as sending a visual cue to the prospective thug that he may wish to consider another victim.

BACK-UP OPTIONS

When mobility is impaired, the options should the firearm go down or not stop the threat are limited. For my purposes, I assumed that there would be a high likelihood that I could be on the ground in such a case and have mentally rehearsed employment of a knife to attack a standing threat’s hamstrings or whatever I can get to in a clinch.

Certain severe combatives moves may be the only options should the knife be inaccessible, but in any case there is a need to confirm whether the normal Plan B is still viable when your mobility is impaired.

SHOOTING

Once I had decided upon a weapon and carry mode, I needed to figure out how to adapt my normal shooting methods to partial weight bearing and crutch support. I had some ideas from dry fire, but as soon as I was able to spend enough time upright, I went to the range to compare and evaluate several methods. Understand that these worked for me and I share the results for informational purposes, understanding that every injury is different, just as each shooter’s capabilities are.

I tried several techniques and wound up with three that each had different strengths. I suppose that each would apply to some degree to most partial weight-bearing injuries involving crutches, and the principles used would apply as a starting point for more severe injuries.

Double Crutched

The simplest method was to allow the crutches to assume the weight while both hands retrieved the weapon and presented normally to the target.

This method was reactive and somewhat intuitive, allowing me to simply get the gun up and shoot without worrying about crutch placement or any preparatory movements. It was also the fastest, with draws coming in (after some practice) around 1.75 seconds to a close target. Accuracy was quite good as well, with handheld groups at 25 yards measuring four inches. Rapid hits were easily delivered, averaging seven hits to a five-yard, six-inch target in two seconds.

There are, however, some tradeoffs that bear considering.

One is that the position requires you to face the threat pretty squarely, which a threat may or may not oblige you with. But the real stinker on this position is that there is very little resistance to impact. Even firing rapid strings forces the shooter to really tighten the “good” leg to maintain stability. I imagine that nearly any contact or incoming fire would cause the shooter to fall backward. As long as the shooter realizes that possibility and is prepared for it, it can work pretty well.

One And One

If the shooter can shoot effectively with one hand, the next method is a good alternative.

Upon receiving an indication of trouble, the shooter blades his support side backward about 45 degrees and posts the crutch behind him slightly rather than neutrally. The shooter grasps the crutch with the support hand, bracing himself for stability and against impact, while the other hand draws the weapon and fires. The firing side crutch rests neutrally under the armpit and provides negligible support.

Draw speed is reasonable at about 2.25 seconds. I was able to get down to two seconds flat by clearing the cover garment with the support hand and then reacquiring the support-side crutch. Accuracy is wholly dependent upon how well the shooter can fire with one hand. I was able to get groups at 25 yards that were just under six inches, so there is plenty of fighting accuracy. Rapid fire suffered slightly compared to using both hands, but I was still able to consistently get five hits on a fiveyard, six-inch target within two seconds from the ready.

This position also allowed a wide arc of possible engagement, covering most of what the shooter could see or scan to. It feels more aggressive and more like a fighting position. The position has some flexibility to adapt to cover, and there is some potential to conduct limited muzzle strikes or hammer fists if the threat gets inside the “hole.”

I found one glitch with the position: on occasion the firing-side crutch would slip out from under the raised right arm and fall. Depending on the amount of weight the shooter can bear, this could be an issue for follow-on movement after the first shots.

As long as the shooter can run the gun well with a single paw, this position has promise.

Crutch Cross-Stick Kneeling

It sounds a little funny, however there are several real possibilities here. One is the ability to worry about one thing at a time. If falling down is a concern, the shooter can mitigate this by getting down on one knee as his cast/injury permits. There he is less likely to fall and, if he does, is unlikely to injure himself further.

Once down, he is fairly stable, and this leads to outstanding accuracy. From this position at 25 yards, I was able to print just over 2.25-inch groups, which were the best I had ever produced with the little pistol, with some Black Hills loads.

Kneeling is also adaptable to cover, so if an injured shooter needed to fort up behind a vehicle or similar object and put a threat on notice, the option is there. It took a little more time to acquire the position, around five and a half seconds, and if the crutches are used to brace the shot, the shooter has a pretty fixed and small arc to shoot in. However, the pistol can be fired strong-hand only while the crutches are simply used to maintain stability.

Throughout the shooting, the pistol was devoid of any lubrication whatsoever. I was hoping to give it every incentive to hang up due to limpwristing or lack of support, but the small auto ran like a top in every position.

RELOADS

Reloads are also worth mentioning.

One reason I went to the M&P9c was the ability to avoid worrying much about reloads, and attempts to reload during the shooting validated that. Standard behind-the-hip pouch placement was extremely awkward from the crutches; think of it more as a transport for additional ammo rather than anything “fast.” Placing a pouch up front is viable for those who are restricted to lower-capacity systems and anticipate a greater need for an extra mag.

REHAB

As the shooter’s rehabilitation progresses, it is again necessary to reevaluate the range of considerations, as the shooter with a slight limp may no longer have the latitude to brandish his roscoe at the same creeps he could have a week or two earlier.

If you are reading this magazine, you are in a demographic predisposed to injury. Hopefully the considerations that helped me through my most recent surgical recovery period will give you a running start should you fall prone to a sports, age or battle injury.