The compensator came into prominence with the popular semi- and full-automatic arms of the early 20th century. Designers quickly realized that dampening muzzle rise would allow faster and more effective follow-up shots. The Cutts compensator is probably the best known of that era and is readily visible on early Thompson SMGs as well as many of the Browningdesigned Remington Model 11 humpbacked scatterguns.

The compensator came into prominence with the popular semi- and full-automatic arms of the early 20th century. Designers quickly realized that dampening muzzle rise would allow faster and more effective follow-up shots. The Cutts compensator is probably the best known of that era and is readily visible on early Thompson SMGs as well as many of the Browningdesigned Remington Model 11 humpbacked scatterguns.

However, from this era up until the 1960s, most primary service rifles and carbines had neither compensators nor flash hiders. The black rifle era changed that, and the debate on the merits of hiding flash relative to dampening recoil or muzzle rise has raged ever since.

Table of Contents

COMPENSATOR CONS

The primary arguments that crystallized against compensators were largely set up as either/or choices. Compensators were loud, which is annoying, and the most effective examples were obnoxious to shoot in close proximity to other shooters. Comps increased flash, already an issue in short-barreled 5.56mm rifles. Comps kicked up debris when fired from prone.

The American military establishment has been prone-centric for-seeminglyever, and this probably had a greater negative effect than you might initially imagine. Therefore if comps did all these undesirable things in their early and most effective forms, then compensators must be inherently bad, right?

Throw in that comps existed predominantly on three-gun competition fields, and flash hiders existed almost exclusively on military issue arms, and the issue became a game vs. tactical one.

I had such a reaction myself several years ago when I realized that a prominent trainer was using a comp on his carbine in demos at a class I was in. Surely he was “cheating,” and I immediately attributed much of what had been truly impressive performance to his “gamer gear,” and he lost some of my respect.

It took several years of progress/maturity and increasingly better comp choices slowly grabbing tactical attention for me to gain some perspective on it. While my opinion had been formed with comps and hiders on either pole of the tactical spectrum, the actual compensator choices emerging had moved toward the middle. Now I can confidently see that a device that allows me to place hits much more rapidly—and may only marginally increase blast and flash—may have some real value and genuine tactical utility.

HOW MUCH DO YOU NEED IT?

Like any piece of equipment being considered, the unit or user must evaluate their mission(s) and actual needs. Is there a risk that accompanies potential gain? The terrain, environment, and typical engagement type/distance of the mission area have to be considered carefully in any choice related to fighting. This applies equally to weapon selection, ammunition, optic, or muzzle device.

Mitigating muzzle flash is generally not the pre-eminent need on most battlefields. Modern advances in preparing for war recognize the probability that many rifle fights are going to happen inside of field-goal range and that the threat may require numerous wellplaced rounds before submitting.

From this generalized scenario, a compensator may be a plus if the accompanying negatives of blast and flash are attenuated to an acceptable level of pain.

For the stateside carbine user, the aversion to compensators is perhaps on even softer footing. A patrol rifle is statistically liable to be used at hailing distance in ambient or better lighting and near service pistol or shotgun armed counterparts who have no muzzle flash mitigation. The patrol rifle user may be in such close proximity to his threat that his ability to deal multiple hits quickly is a real issue.

Enough theory.

BATTLECOMP COMPENSATOR

Over the past 18 months, I have shot around enough BattleComp Enterprises muzzle compensators to have become interested. The devices are inconspicuous at first glance and have a series of small ports arranged in rows to do the work. The comps have little noticeable increase in flash, and blast is a truly minor issue.

One of my least favorite things is getting lateral blast from another shooter, and I genuinely dislike shooting next to many available comps. I have no issues with the BattleComp. Shooters who’ve taken them into the shoot house or, more importantly, been in rooms with a BattleComp-equipped shooter report there is no drama.

Watching shooters in prone, I noticed there is a slight increase in dust signature, but not to a point that it concerned me. The BattleComps did not dig into the ground the way some comps are known to. Rising dust can quickly offset the ability to shoot rapidly or well, but shooting prone over dry ground is a challenge whether using a standard A2 birdcage or other device.

TESTING

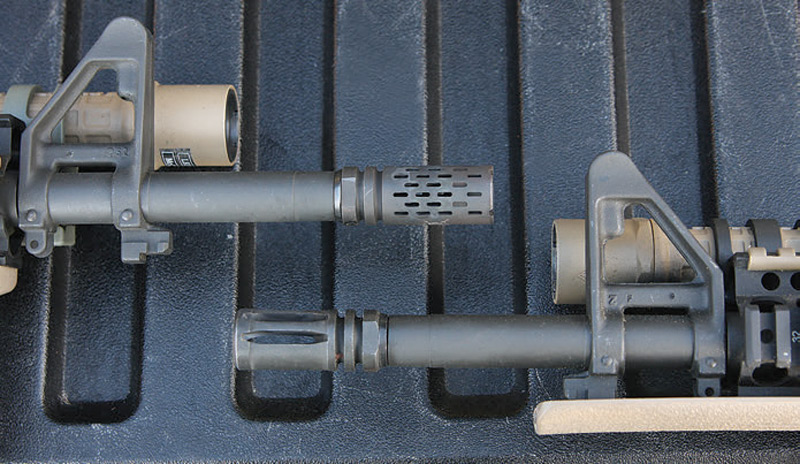

That is admittedly fairly anecdotal. However, I am more interested in the “gain” side of the equation for the hard to measure, but possible, increase in risk. In a recent class, I had a chance to take two identically set up Bravo Company EAG carbines, one with the A2X birdcage and the other a BattleComp, and run drills with some shooters to get data.

Fortunately I was able to use shooters from different user groups. One was a novice, on his third morning of a three-day EAG class—his first ever exposure to shooting an AR. At the other end was a special mission user with years on the guns.

Test 1: Close-Threat Engagement

The first test was set up to see what happened when a shooter put the pedal to the floor, evaluating the effectiveness of the BattleComp in a close-threat engagement requiring multiple shots. The shooters began with the rifle at the ready and, upon the signal, fired five shots as fast as they could hold the hits to the eight-inch vital zone on an EAG target ten yards out.

The comp made a noticeable difference with the novice shooter, taking .15 second off each shot to the vitals. Consider that the simulated threat downrange—operating at max physical speed—can launch his shots at that .15 speed, so the advantage is interesting and could stop the fight with one less incoming round. The total time for all five shots averaged 3.26 seconds for the standard carbine and 2.57 seconds with the comp.

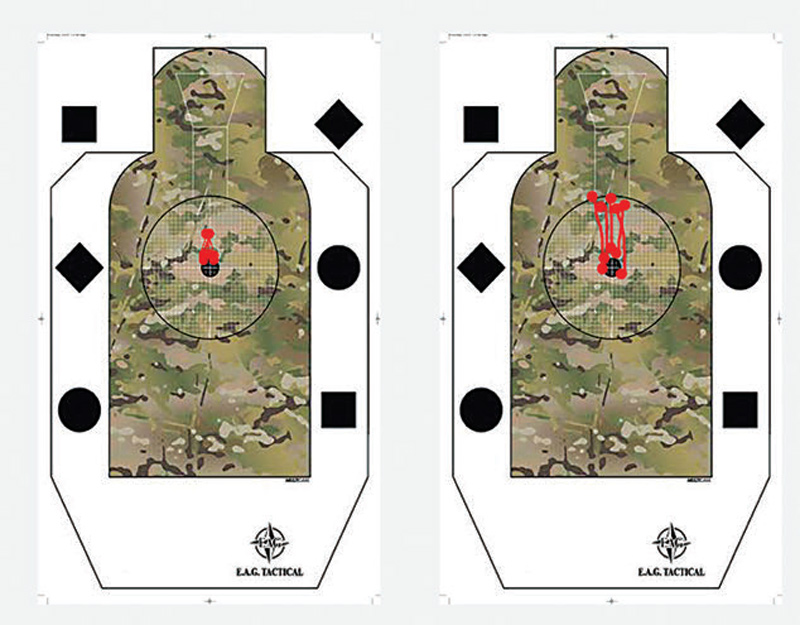

At the other end of the experience level, the comp made no statistical difference in time. The shooter repeated identical splits. However, the target told a different tale. The .97 cumulative was spread over most of the eight-inch circle with the flash hider, while the BattleComp’ed EAG carbine was able to hold the five-inch head box with room to spare.

Test 2: Barricaded Shots to Single Target

The second test consisted of three barricaded shots to a single target at 20 yards to see what advantage was possible leaning out from cover. The BattleComp took .44 second off the experienced shooter’s 3.29 hider total—a pretty significant plus. Switching to the support side and running the same three shots to the other side of the barricade, the performance gap widened. The flash hider yielded 4.25, while the comp slashed that, giving a 33% decrease to a 2.82- second average. To put it in perspective, the comp allowed the shooter to outshoot his strong-side flash hider score by half a second from the support side.

With the new shooter behind the barricade, the results were similar in the percent difference in average time. However, the distance and recoil factored in and the shooter shot much better with the comp attached. Several of the follow-up shots with the flash hider equipped gun pickled out of the vital zone into loose gut hits. My theory is that the relative stability of the comp allowed the shooter to better press the trigger, since the dot stayed near the center of the target.

When the dot started bouncing around in recoil, he seemed to snatch on the trigger in trying to go fast.

Test 3: Five Targets, Ten Yards

The final test was against a bank of five EAG targets at ten yards, the shooters putting one hit as fast as possible into each target. This was done to see if the comp had any tangible effect on close multiples. The targets were each spaced about two feet apart. You might not expect a muzzle compensator to affect that scenario, but with the beginning shooter, there was a 17% average boost from the comp, allowing him to hit the row of five .73 second faster on average. Who’da thunk it?

The experienced shooter had a statistically identical performance with both devices, but said the comp-equipped carbine never left the plane of the vital zone, allowing him to easily drive straight across. In comparison, the flash hider allowed the carbine to recoil just above the vitals and required the dot to be driven back down while tracking to the next target, tracing a lazy M-shaped arc.

SO WHAT?

At the novice level, these simple performance tests indicate great potential for the BattleComp to boost performance pretty quickly, both in accuracy of follow- up shots and speed.

At the high end, this is a tool to allow disadvantaged follow-up shots (on the move, sloppy mounts in reactive snap shots, leaning out from cover, support side, et al) to close the gap on normal performance.

Under stress, a large percentage of shots tend to become somewhat disadvantaged compared to well-prepared range performance. If an entry team member with a comp can pour a nonstandard response into a fist-sized area rather than a volleyball-ish one, that is probably good.

The results point toward some real capability gains—enough to get a shooter to a higher level of performance that could make the difference in a multiplerounds- required fracas.

The future need not be a “flash hider or comp only” choice. If a stateside agency is spec’ing out a rifle, it is worth looking into compensation. Don’t be the last die hard clinging to suppressing flash out of a sense of tradition or tactical piety.

Cost is the only factor preventing me from retrofitting most of my carbines with BattleComps right now.

1 comment