ANY competent gun carrier knows the four universal firearms safety rules, so why does almost everyone, especially police and military pros, continually violate them?

Table of Contents

FOUR RULES

Treat all firearms as if they are always loaded. Never muzzle whom or what you don’t mean to shoot. Keep your finger off the trigger until ready to fire. Be sure of your target, as well as the background and what is near your target. While these four rules can be phrased differently, the wording is immaterial. Their intent is universal. They should be seared into the minds and bodies of every professional and ethical gun owner and gun carrier, period.

If they are not, then seriously do yourself, your family and everyone you may ever have to protect with your weapon a favor: stop reading and go back and memorize them before continuing. Recently a TV reporter asked me to comment on the heartbreaking tragedy of a three-year-old who shot herself because her father’s handgun slipped unnoticed from his pocket. This tragedy is the polar opposite of what the sheepdog/warrior/protector of life and freedom should and must epitomize.

As an armed professional warrior and teacher, I demand of myself that every friendly I come in contact with should be safer and hopefully happier because of our meeting. Like physicians, we must first do no harm. I don’t think this gets emphasized enough. I see far too many skull tattoos, smoking gun cartoons, and “Let God sort ‘em out” t-shirts. Don’t scare the sheep!

THREE CONDITIONS

Equally important is weapon status. Conditions One, Two and Three define weapon status and degree of attention.

Condition One: Round in the chamber, loaded magazine in the well. This status should only be used when the weapon remains in the immediate control of the operator, i.e., on his person, in a secure holster.

Condition Two: Chamber clear, loaded magazine in well. If someone then discovered the gun, especially a child, they cannot immediately shoot themselves. They’d have to chamber a round first. That gives the operator some time to regain control of the weapon. Time equals distance equals survivability.

Condition Three: Chamber clear, magazine well empty. An unauthorized user (e.g., a child) has to find a magazine and load it, or find the loaded magazine, or figure out how to drop a live round in the barrel via the ejection port. All these are possible for a young child and, as they grow up, so do the probabilities of success charging the handgun increase. But Condition Three requires more time and effort for anyone to fire the weapon.

The goal is to keep the handgun immediately available, reasonably safe and quick to load in an emergency. As a father, I wish that dad who lost his child had had a plan and trained. I doubt the dad even knew the three conditions.

But what about cops? They most certainly were taught these conditions. But do they employ them? How many times have we seen undercover officers stick a hot Glock in their waistband? How many times have we seen an officer shove a hot handgun in an unlocked drawer and turn away—sometimes with suspects in the room? I personally know of federal agents whose kids have been killed because they violated the laws of these conditions.

The lesson? Like the four rules, the three conditions should be branded in our brains. And then we must follow them like the Ten Commandments hewed in stone—without variation! As a long-time SCUBA and sky diver as well as paratrooper, I can tell you with dead certainty those who die in dives and jumps are the very inexperienced—and the very experienced. Why the experienced? Because they become lax.

There are more than enough tragedies and gun grabbers in our lives. We don’t need to add to them nor give them ammunition. At Warriorschool and my Handgun Martial Arts Center, we push the training envelope to the max, but never ever the safety envelope.

REALITIES OF THE RANGE

Most law enforcement and military training is derived from sport shooting. IPSC and IDPA stuff are competition. A game. As soon as you give something a sport status, folks will start to game it. Cut corners to win. Do things in such a way as to raise their score and lower their time.

The truth is that shooters in competition do things differently than shooters in a gunfight. This can lead to trouble. I’m not against sports or competition. I’m not saying competitive shooters aren’t competent protectors or gunfighters. But I’m training to be the best protector of life and freedom I can.

That is my personal choice of my development as a warrior. I don’t want any confusion about two types of techniques if and when I have to gunfight. And my level of warriorship, protectorship, sheepdogship, is that I train for the gunfight each, every, and all the time I employ my handgun. I simply don’t compete. Except against myself, privately.

There are still innumerable rangemasters, safety officers and firearms instructors mandating students point their handguns over the magic safety of the firing line downrange when loading. This is, of course, so if they have a Negligent Discharge (ND), it will be into the dirt and not over the berm.

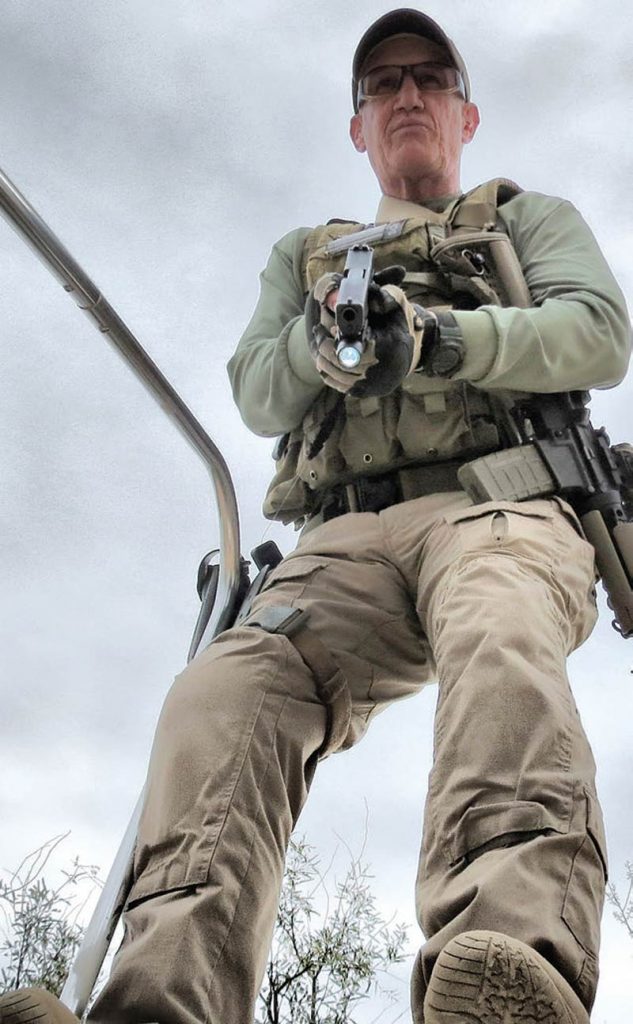

But the combat load, speed or tactical reload, and immediate action should all be performed in the operator’s workspace, elbow bent and locked into the shooter’s central torso and wrist locked straight, muzzle not occluding the shooter’s view so that the shooter looks over the muzzle downrange at the threat.

UNDER PRESSURE

Proactive action in a non-threat environment makes the position immaterial. But everything changes drastically when the gunfight starts. Physiological and psychological stress factors work on the shooter, bringing the onset of multiple phenomena such as tunnel vision, and afterwards adrenaline shake off.

The bent arm, locked wrist looking over the muzzle at the tip of the nose minimizes the effects of such factors. It’s also much easier to perform behind the steering wheel of a car—a place where many cops find themselves gunfighting— or even on their backs. Try an extended arm reload or combat load behind the wheel of your car or on your back. The gunfight is not square range and I have yet to see one that started with a buzzer.

Again, proactive action in a nonstress environment will let a shooter get away with a lot, such as laying his finger alongside the slide. But put that same shooter into a lethal-force situation (even if he doesn’t fire his weapon) and have him move and perform multiple tasks at the same time. Watch the trigger finger that sat passively above or, even worse, over the trigger guard and see what happens. As the shooter has to perform more simultaneous and complicated actions and movements, the finger will slide into the trigger well!

I have seen it happen with so many military, LE and private citizen shooters over my decades as an instructor that I have lost count. I’ve taken cops’ fingers off the triggers as they hopped fences and agents’ fingers off as they covered suspects. I finally started filming my students clearing rooms or running FATs scenarios. They simply didn’t remember or couldn’t believe they were putting their finger on the trigger. But they did.

Now throw in a gun grab or forceon- force and you have a high probability of an unintentional discharge and accidental shooting. The real answer is to train shooters better as beginners.

A BETTER WAY

Abandon the Secret Service straight finger. Bend the finger above the trigger guard with active pressure against the slide retention pin. Press forward, not in on it because some weapons, such as the infamous Beretta 92, can be easily disassembled because of it.

Keep active pressure on it until you decide to press the trigger. It’s the passive position of the finger and the lack of pressure that are the roots of the problem. If a bad guy does get close enough for a gun grab, the trigger finger then convulsively closes on itself—not the trigger. No ND, no unintentional shooting.

The benefits of the bent finger don’t stop there. If you suddenly have to shoot and your finger has been straight above the trigger well, there is a high likelihood you will over-access the trigger and jerk the shot. I have seen precisely these phenomena in a number of police reactive shootings.

But if the trigger finger is bent above the well and you need to suddenly shoot, the bent finger drops just about ideally, to the middle of the first joint onto the trigger, making that first cold and adrenaline-laced shot more accurate, safer to innocents, and more likely lethal to the bad guy.

WHERE’S YOUR MUZZLE?

The other problem with straight-arm techniques is that they are fine on the empty square range but unrealistic for a crowded meth trailer, SWAT stack-up or mall with innocents running past you. Remember the basics: Never muzzle what you do not intend to shoot. In a crisis environment filled with innocents fleeing an active shooter, you simply cannot afford the risk of leveling your muzzle except on the threat.

At Handgun Martial Arts Center and Warriorschool military classes, if your muzzle is horizontal, you should be pressing the trigger. I have experienced a few exceptions to this in my Special Forces days, when I was Australian rappelling with an M4. But then my body was not horizontal.

That brings me to the most common and dangerous violations of the fundamental safety rules: Holding a suspect at gunpoint or clearing a room. It’s dangerous for the suspects, the innocents in the room and the operators. In the bad old days of law enforcement, we performed both of these actions at the horizontal. If post-raid or post-home invasion, a supervisor or officer walks up and bumps or startles you while you muzzle the suspect, the probability of an unintentional discharge and therefore accidental and bad shoot elevates drastically.

Room clearing was even worse. We used to muzzle everyone in the room! In Iraq, one of my Ranger instructors stopped from shooting a boy who surprised him in a night raid on sheer intuition.

Though we announce and command “SHOW ME YOUR HANDS!” what I call the deer in the headlights phenomenon often takes over. That is, it takes a suspect a while to input past the shock of the event. Looking over a slightly lowered M4 while still maintaining a good shoulder stock weld opens the tunnel as well as allows the whole room—and the suspect’s hands—to be seen.

PREFERRED HOLDS

Research done by my pal Steve Ryan and other NRA Law Enforcement Firearms Instructors shows that time onto target is not significantly lengthened by holding lower. Where precisely is that hold? At the suspect’s feet. The probability of an ND is minimized and, if it does occur—as we have seen on multiple cruiser and phone cameras—the bullet should end up in the deck.

The ideal position for this is the Guard: arms locked out, muzzle just at the feet of the suspect. This is also the safest position for a post-shoot sequence scan for additional threats. But if there is no suspect and you are simply covering a corner or doorway and you don’t have adrenaline dump, the Guard can quickly become fatiguing.

The answer is the Low Ready: pull the elbows in until they are touching the torso, sliding them inboard until the wrists are straight. Elbows and wrists are often overlooked safety keys. They provide anchor points for the operator to move and perform complex multiple tasks without NDs.

I respectfully disagree with my colleagues on the current trend to place the heels of the handgun against the torso with wrists bent and elbows free. While this is a great starting place and will prove how quickly a new shooter can become accurate by simply pushing out and pointing the gun into the target, it is neither a safe nor accurate gunfighting stance.

Again as soon as we shift into a reactive mode in a non-square-range environment with friendlies on either side, it soon becomes evident that unlocked wrists and unanchored elbows allow the shooter to muzzle anyone on his left or right and even himself!

Safety rules should be tailored not just for the square range but for the grim, ever-changing reality of the gunfight. Anything less is failure to train to the standard of life and death.