The present economic difficulties have led many to curtail their shooting activities and training. Others have sought prudent ways to trim any fat in the shooting budget while maintaining their skills. As we look at how to stretch available dollars, there are a few traps to avoid. These come from the mother of all wisdom—experience—and I pass them on in the cheerful recognition that most will read these and only agree after learning the hard way for themselves!

So here we go:

Even at current ammo prices, risk posed by old rounds; scrounged duds; or dented, damaged, and compressed pick-ups is not worth it, even if they might fire and save a few pennies.

Table of Contents

BELTS

At this point in your shooting career, quality holsters go without saying. However, there is something just fundamentally wrong with a quality pistol flopping north-south and east-west as it fights a leather strap that a puppy wouldn’t even enjoy chewing.

A quality belt should hold the trousers in the desired position across the range of normal to moderate activity. Adding a few pounds of gun steel tends to add to the requirement for what it takes to keep the pants up. Providing a steady and repeatable mount to the holster for smooth presentation of the weapon increases the required width and thickness further. These days there are a wide variety of quality belts available at unprecedented low cost, so there is less to excuse the yuppie latigo that is losing a fight with gravity for your gear.

As a highly unscientific rule of thumb, if you grasp a gunbelt around its center and can flex it more than 10-15 degrees, you will have problems with flopping and sagging.

For the young and svelte, a guideline to consider is that airweights can work on a stiff, single thickness belt with a width of 1 1/4 inches or a smidge less if the holster loops fit tightly. For pistols 32 ounces and under, a 1 1/4 inch double thickness belt will probably do. Serious pistols that are heavier than that really need a stiff 1 1/2 inch belt.

For the more “girthy” among us, some trial and effort may be required, but the better the belt, the more likely it is to do its job.

Quality functional leather and nylon belts are available at every price point. To prove this, I recently used the flex test mentioned above to find a perfectly serviceable belt at Wal-Mart for less than $13. However, a good belt is an investment. I still use a Milt Sparks’ gunbelt that is nearly 15 years old and have gotten numerous hard years and deployments out of a sharkskin Rafter S belt that was a relative bargain.

Simple battery tester and spare batteries are great investments that will repeatedly save the day.

BATTERIES

Batteries are expensive, range time is precious. You load up your gear and drive that big truck out to the range at however many dollars per gallon. You set up the chrony to clock that special homebrew, and the batteries are dead. No worries—the shooting timer runs on the same 9 volt—but after disassembling it, the thing barely zaps your tongue upon op check. On a streak like this, care to guess what the status of your riflescope’s illuminated reticle on this overcast day is?

I learned this the hard way after loading up for a class and having my red dot sight fade out. I pulled my spare (who needs more than one spare, the things are supposed to last for years, right?) and found it hors de combat as well. Luckily the assistant instructor was more prepared than I, and all ended well.

My next move was to get myself to a battery store and buy a simple battery tester. It is amazing how many “new” batteries are not so fresh.

Recently I went through an entire package of new major-brand AA lithiums, with each one testing out right at the edge of the “replace” mark on the tester. So consider purchasing a tester. The new-in-the-wrapper spare is less reliable than a tested checked backup. SOPs to check batteries before you are on the range or an operation will save you the cost of unnecessarily replacing batteries on schedules, or the much higher opportunity costs of missing out on training with your battery-powered widgets.

At today’s ammo prices, it is pound foolish to scrimp on targets and risk losing track of where that precious round went.

TARGETS

Ammo prices are on a steep climb—targets are not. The whole point of firing a shot in training is to hit something. If the target is so shot up that it is unclear whether the holes are yours, your partner’s, from the last drill, etc., then the exercise has become ineffective, flinch-inducing dry fire with a bang.

Targets range from less than a penny to around a half dollar each. Splurge for whatever target is going to best help you accomplish your training goals for that day’s session. The few dollars in targets are inconsequential in relation to the expense of the gas to get there, range fee and ammo. In addition, and this is important, bring 10 more targets to the range than you think you will need.

Once at the range, it’s not the time to scrimp. Every time you switch drills, lose track of what’s what, or have a scheduled cold line, reface the target! Index cards (3×5, 4×6, and 5×8) make great impromptu targets and can be had in bulk for less than a penny each. Old paper grocery sacks can be cut into refaces to resurface cardboard silhouette targets much more quickly and completely than pasters, and at no cost. There is no excuse for holey targets that beg the question, “Where did it go?”

It took me years to come around to the fact that the target is an equal partner in the triangle between it, the shooter and the weapon system (firearm, ammo, optic, magazine[s], and lube). It is the easiest but least effective way to save money, yielding pennies saved and costing dollars wasted in ammo and range fees.

I once conducted a test of some PDWs (personal defense weapons) for a special project in my organization. I had limited time with each vendor’s weapon. One vendor took me to task—and correctly so—for the way that I was husbanding targets through the test, trying to record multiple strings on the same bull at the risk of losing track of valuable data. Since then I have gradually forced myself to spend on targets until I have a decent variety available to suit most purposes. I also consciously take to the range many more targets than I think I’ll need—I often use nearly all of the “extras” I bring. I can tell you, for a few dollars more, I am a much better shooter and get much more satisfaction out of my training.

In a similar vein, I cringed at the cost of good steel or polymer targets until realizing how much more I got out of shooting my expensive rifles, optics and ammo against them. Price a box of good quality precision ammo or three. Do you really want to spend that putting holes in paper that you can’t see well without a high end (read: expensive) spotting scope? That steel target is not as expensive as you think.

If belt flexes this much under finger pressure, it will struggle to hold trousers and gun up, whereas quality belt will provide stable and repeatable platform for the weapon.

GUNSMITHING

In this area you can also put a dime in the meter now or pay the $20 ticket later.

I went through a Browning Hi Power phase a few years back (who hasn’t at some point?). I was given a beautiful one by my wife—I mean, I was given one by my beautiful wife, and I decided it needed a custom thumb safety on it. I wanted a Novak’s, but it was slightly pricier than another brand that was available second-hand from a fellow shooter. I went cheap and reported with my find to the 2111s in the armory. None of us knew much about HPs but had a good bench vice, a mallet and just enough sense to be dangerous. Can you guess where I’m going with this?

Of course we got the square peg mashed into the round hole, and the thing almost worked until the safety began walking right out of the frame under recoil, coincidentally not making the weapon “safe” any more. I looked at Novak’s website and decided that I could not afford the shipping on the pistol, so I ordered the part only and took it to the “pistolsmith” at a large local gun shop.

He assured me he could figure out how to fit the safety using his manuals. I failed to get a firm price estimate on the front end, and on the back end realized that the man fancied himself quite the high-end custom artisan, billing me much more than the rate at Novak’s shop with its long and worldwide reputation. Lesson learned at considerable expense. (Karma may have been involved when the offending gunsmith’s store burned down a year later.)

I have had an embarrassing run of misadventures where I should have paid the established professional to either fix my rifle or pistol or fit a high-quality part from the beginning. I always end up paying them in the end anyhow, so have resigned to paying up front and saving myself the time, frustration and additional cost.

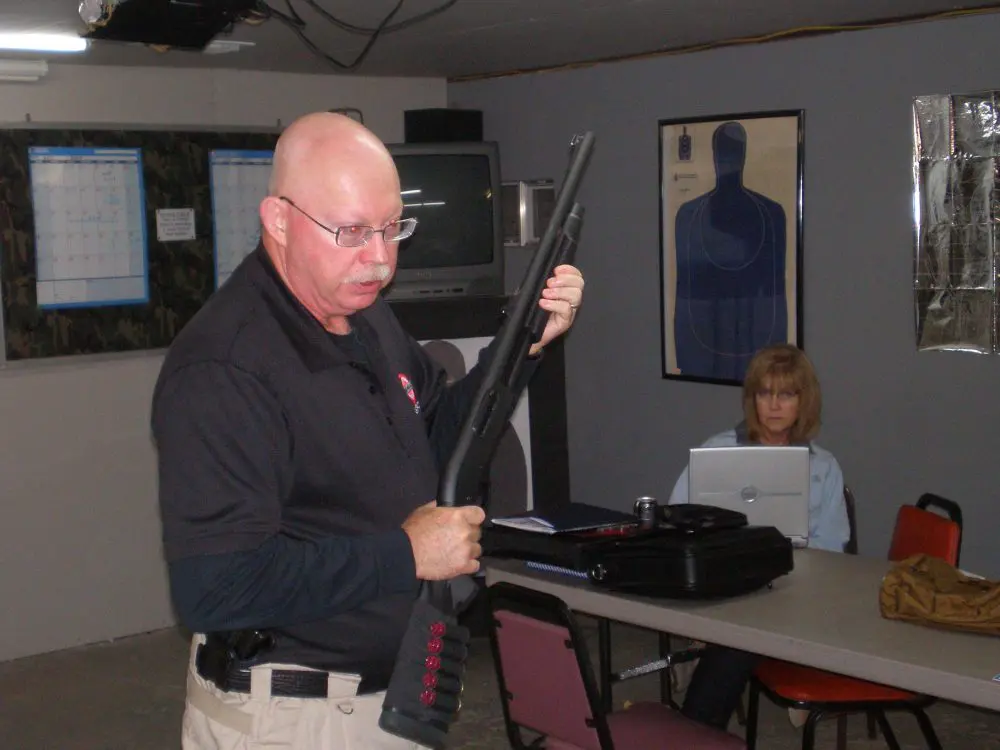

This shooter has acquired enough magazines to get through full day of carbine training without interruption, which will allow him to get much more out of the class.

AMMO

Few things make me cringe as much as recalling the stupid things I have done to save a few bucks on ammo—even before the prices went sky high.

Raid the dud box? Check. Reloads from random dudes? Shot ’em. Rechamber rounds where the bullet got hung up and compressed into the case? Yup. My first several thousand rounds of .45 ACP as a kid were corroded steel-cased stuff from 1942.

Did I say corroded? I meant horribly rusted to the point that some wouldn’t chamber and most cases split upon firing. But they were free and I was shooting a .45! Both the too-valuable-for-that-treatment pistol and I survived the experience, but dodging damage failed to teach me.

Most of my early shooting in centerfire was conducted with WWII-era surplus ammo, and I suffered through hangfires, duds, split cases and whatnot until I could actually afford to buy real ammo. Even then, I occasionally returned to nasty ammo to stretch my money. I stopped when a .38 squib stuck in the barrel of a prized Smith & Wesson Model 15, nearly ruining the barrel.

I have a shooting buddy who has spent the equivalent of several cases of Black Hills match ammo in 147-grain ball battlepacks from random semi-developed countries, none of which has proven remotely reliable and all averaging minute of trashcan lid. But they were a bargain!

Anyone who has been to a carbine class lately knows the issues that cheap ammo brings with it. Popped primers, missed crimps, inconsistent overall length, etc. There always seems to be that one shooter who scrimped on ammo and struggles with running his gun because of the resulting QC issues.

Ammo is expensive, but going cheap is not worth the aggravation at best and the risk to weapon or shooter at worst.

MAGAZINES

This downed horse is fairly well beaten on buying quality mags, and the choices in reliable mags these days are plentiful. However, the answer to how many magazines one needs is best answered by “More!”

Here again I have gradually come around to first buying quality and then quantity. I used to go with the minimum required magazines at training or competitions. My reasoning was that I could keep up with three or five and be absolutely confident in them, more so than a boxful. It finally dawned on me when another S.W.A.T. writer showed up with enough prefilled mags to get through an entire three-day class, that he was getting a lot more out of the class than I was, as he was able to relax between strings while the rest of us were frantically stuffing rounds into mags. The next class I attended I had my own boxful!

The shooter who has barely enough magazines to get through is generally a drag on the firing line. In individual training, the shooter who only has one or two mags invariably babies them, training gingerly to prevent damage to them rather than aggressively stripping them out of the weapon or letting them fall to the deck. You generally don’t see that with the shooter who has a dozen. The stingy shooter will also use the mag past its service life, trying to squeeze a few more miles out after the magazine stops locking the bolt back, falling free or begins inducing stoppages.

The present political situation being what it is should only provide more impetus to hurry and buy additional magazines—now!

MILSPEC PARTS

I had the good fortune to spend considerable time sequestered away where all weapons and ammo were milspec. I honestly just couldn’t see what the hoopla was all about in regard to parts quality and breakage issues with AR-style weapons. I saw a lot of rounds go downrange and rarely were stoppages attributable to the weapon. They generally resulted from old, worn-out magazines or poor lubrication.

Then I borrowed a parts gun to compete in a three-gun match. It produced more double feeds in one morning than I had seen in several years. I later had a cheap, commercial CAR-style stock and extension tube on a personal rifle. No amount of tightening could keep it from unscrewing from the lower receiver with only gentle pressure. I finally got the memo and replaced it with a proper quality tube and a CTR stock and then went ahead and staked the gas keys on the corresponding commercial-quality bolt. It has been a solid performer ever since.

Considerable time in mixed enrollment classes and competition has made me an absolute stickler for milspec parts of known provenance. It is amazing how few issues there are when shooters use milspec parts and avoid offshore aftermarket junk. But like all our holster boxes full of second-rate junk, each shooter has a hard time resisting “as good as, but much cheaper” appearing parts.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Some things are just worth the money, even if they seem at casual glance to be unnecessary. The journey can and often does prove the extra cost and frustration of that cut corner.

The economy and pricing situation have made some ripples in the training community and may cause more disruption before it is all over, but with wise spending on some of these critical items, the shooter will wind up better prepared and better invested in his kit.