I’ve been fortunate to have done a lot of shooting over the years. Moreover, I’ve done much of it under the tutelage of professionals, whether of the itinerant type such as LFI, OPS, or ASAA, as well as schools with permanent campuses such as Gunsite and Thunder Ranch. I’ve done enough training over the years to consider myself a serious student of gunfighting. Why then would I attend what I initially thought would be an advanced first-aid class?

One of the many benefits of being a training junkie is that since you are training with and sometimes competing against other serious students of gunfighting, at some point you realize you’re not the best in the West. And even if you were, you can always have a bad day when you or one of the guys on your side takes a bullet.

After applying tourniquet on left thigh of victim in yellow shirt, rescuer reacquires his Glock and prepares to clear remainder of house.

Consider this sobering thought—people get shot on shooting ranges, too. The more realistic one’s tactical training, the more dangerous it becomes. I’m willing to bet that many S.W.A.T. readers have been swept by the muzzle of someone else’s loaded gun. Students in classes shouldn’t do this, but it does happen.

And the most compelling reason for attending this course: our world is becoming more uncertain by the day. When the next natural or manmade disaster hits, do you really want to rely on the medical infrastructure being in place to administer care to your loved ones or yourself? If the nearest hospital is impossible to reach, has turned into a smoldering crater, is underwater, or (fill in one of several possible scenarios here), wouldn’t you rather be able to perform some emergency medical procedures yourself? That’s why I was spending a long weekend at Gunsite.

Table of Contents

SHROUDED IN SECRECY

Articles of this type usually begin with the instructor’s name and a list of superlatives including his qualifications. Not this one. For security reasons I cannot identify this instructor, but can reveal some of his background. He was an Army surgeon during the Vietnam War and beyond. Surgeon, not medic: he was an M.D. and field surgeon in a special operations unit and, for reasons he would not share with me, must still remain anonymous. Therefore I will refer to him as Dr. Doe.

Years on battlefields all around the world have given him an excellent command of his subject matter. He is a gifted teacher who can impart that knowledge to his students.

Those who are seeking knowledge in this area should consider the Gunsite Emergency Medical Preparedness Class a necessary primer or base upon which to build one’s plan to become truly proficient in emergency medicine. This class may not be as sexy as a high-round-count carbine class, but it is at least as necessary and one that a civilian student is more likely to put to practical use.

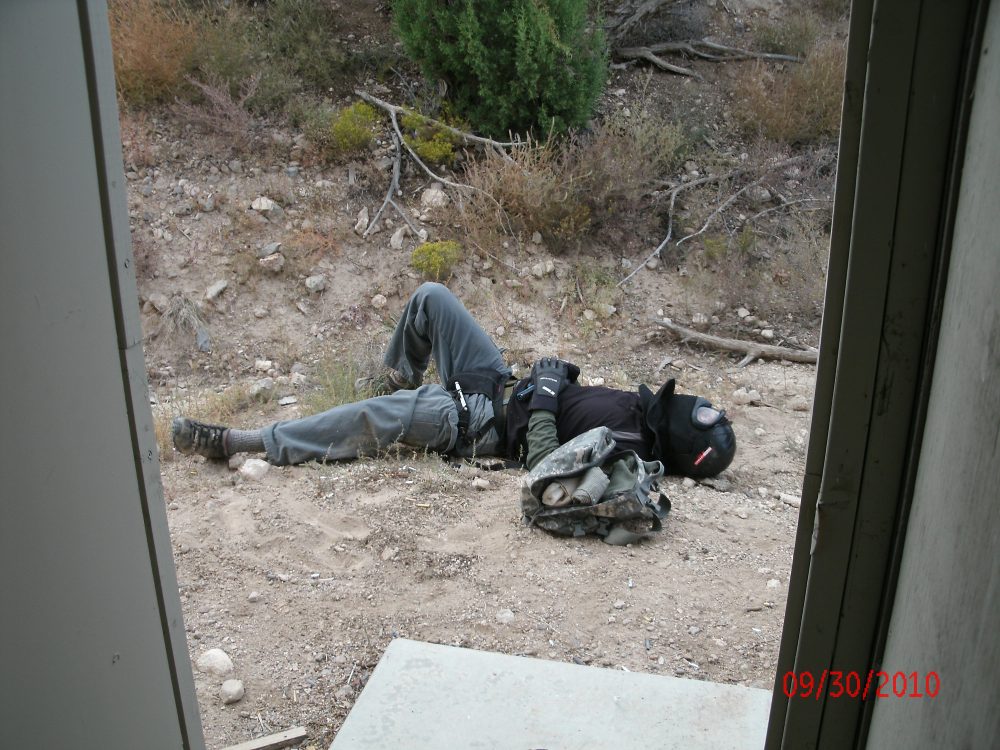

You’ve cleared the house and are ready to treat injured personnel. This threat was downed outside the house by a sharp-eyed shooter from within. Once you are inside a structure and have begun clearing, some threats may still be outside waiting to shoot through a door or window. You can’t treat wounded if you’ve just been decked by some crook who tagged you from the backyard!

TIME FOR CLASS

Space limitations prevent a detailed description of every topic discussed and every exercise performed, which included force-on-force drills using Simunitions. So instead I will provide an overview of what the training entailed and what a student can expect from this class.

After administrative matters were completed, it was time to take notes from Dr. Doe’s lecture and PowerPoint presentation. Both of these were very professional and well thought out. The class was advised that a primary goal was to break the habit many people have of standing around in a circle wondering what to do after someone has been injured instead of taking action. It was also stated that we would focus more on medical treatment than shooting skills.

Doc stressed that what works in a hospital does not work on a battlefield or in the middle of a breakdown in the social order, such as what happened during and after Hurricane Katrina. In such environments, the medical provider must be able to operate under hostile fire and limited visibility and without such conveniences such as labs, x-rays, care flights, or worrying about IEDs, etc. Plus the possibilities of extreme environmental conditions such as cold, heat, wind and rain exist.

And let’s not forget the possibility or even likelihood that you will be operating in the dark where you must maintain light discipline to avoid attracting incoming fire and winding up with more casualties to care for, which could include yourself. You may be the one with the most medical training or the only one left uninjured.

Dr. Doe critiques student’s performance after riot scenario.

PRIORITIES OF CARE

Students were instructed not to focus on minor first-aid problems but instead on immediate life-threatening injuries, with perhaps the worst being a massive hemorrhage where the patient will bleed out in 60 seconds or less. The lectures were interspersed with relevant drills such as getting down on the floor with a partner and doing an examination of the entire body by feel while maintaining the lowest possible profile (incoming rounds, remember?) in order to locate the source of that possible hemorrhage. If the hemorrhage is on an extremity, the best solution is usually a tourniquet, as it’s quick and may allow the injured combatant to get back in the fight. In fact, extremity exsanguinations represent no less than 60% of treatable KIAs, while chest wounds account for only 30%.

The drill described above, where students examine one another by feel while remaining low, is just one way you might perform triage (determining which members of a group have sustained the most severe injuries and require the most immediate attention). Triage may force the provider to deny care to those who are so severely wounded that attempting to help them would simply be a waste of time, and to focus on those who stand to benefit from medical attention and as a result may be able to get back in the fight—tough stuff indeed. And so was spent Day One.

This rescuer just made the heart-wrenching decision to leave a wounded woman behind after administering what help he was able to. If real, this scenario might leave one with nightmares. However, if he fights to the end and dies, he can’t help anyone else and has sacrificed himself for nothing. Having to make such a decision is tough, but provides valuable food for thought.

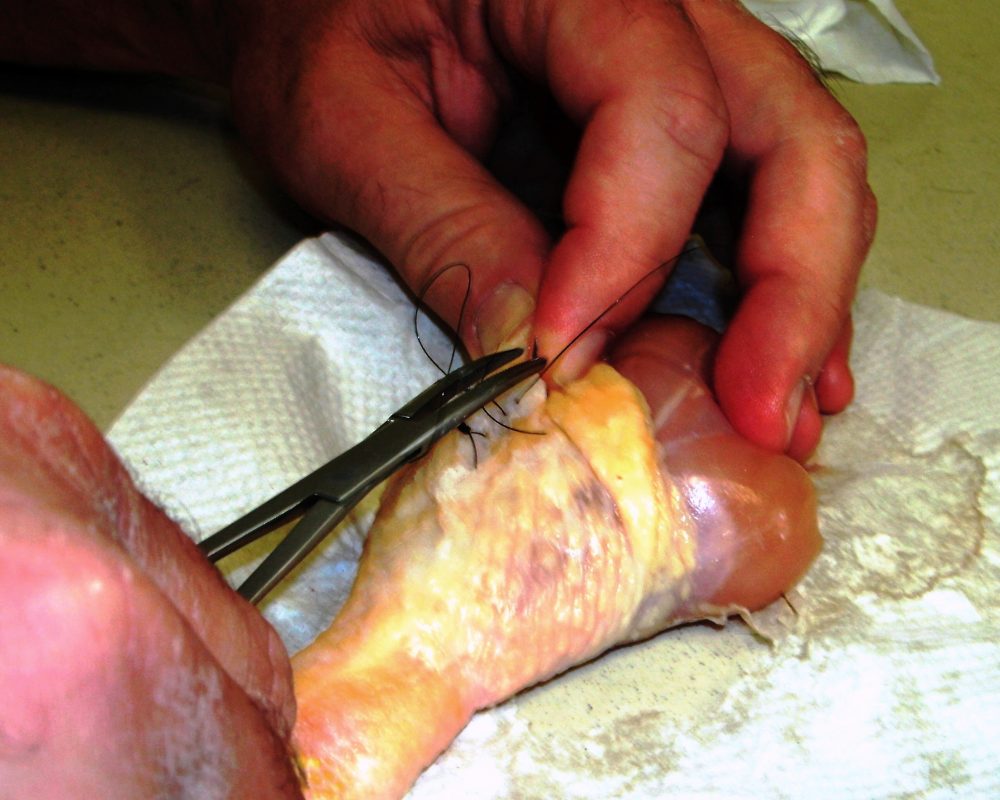

The next morning, Doc instructed us on various ways to deal with bleeding. From applying pressure to squeeze vessels shut, to practicing with different types of tourniquets, the class received grounding in dealing with blood loss. We practiced wound closure with sutures, Super Glue, and staplers. It was interesting to work with sutures, but for me at least, unrealistic to think I could do it in a real crisis. I will add a stapler and Super Glue, both liquid and gel, to my kit.

Next was a discussion on pain control. Interestingly, it was pointed out that factors such as fear, cultural expectations, and even the patient’s level of trust in the care provider have much to do with that patient’s perception of pain. In an unexpected crisis where a non-professional is administering care, his calmness and certitude may be the only tools available for pain control, since prescription drugs will likely be unavailable. Local anesthetics such as lidocaine and how to use them were addressed, in the event that they may be available.

Fortunately a fair degree of pain relief can be achieved with over-the-counter medicines such as Tylenol, which Dr. Doe believes is very underrated. Above all, don’t use alcohol, as it may result in a violent and unpredictable patient.

THE REAL THING—SORT OF

Simunitions (SIMS) ammo is basically a cartridge case with a plastic paintball powered by a primer. It works with real guns that have been modified, which permits a high degree of realism during training. After lunch, the class participated in two such SIMS exercises. The first involved working with a partner in a vehicle approach to rescue a downed victim. Partners approached the victim, exited the vehicle, and provided cover fire for each other until one reached the victim. One student was required to assess injuries, provide appropriate remedies such as bandages and tourniquets, then get the “wounded” student back to the vehicle while the other rescuer provided cover.

The next drill was conducted at one of Gunsite’s shoot houses. One scenario was that three students were visiting a friend in a remote ranch house on the Mexican border when an AK-wielding drug smuggler attacked them. He managed to down two of the three visitors before escaping, leaving the third to treat the wounded while staying prepared for the smuggler’s possible return. It was a good exercise in tough decision-making, as the uninjured student had to determine whether to treat the injured, which meant being less able to deal with possibly re-entering the gunfight. Guns had to be holstered while medical supplies were unpacked and arrayed for use. At the same time, the student had to try to maintain situational awareness and gun safety by not crossing the victims or himself with his muzzle.

Juggling of priorities was a recurrent theme throughout the class, and this drill provided two interesting side notes. We were not told not to actually shoot the threat(s) during force-on-force drills because SIMS rounds do hurt and cause bruising (even though all appropriate protective gear was worn). This did not always happen, and I had the bruises and welts to prove it.

Gunsite Emergency Medical Preparedness Class was so comprehensive that students were given instruction on advanced methods of wound closure. Student uses hemostats and curved suture needle to sew up a chicken leg with black nylon thread. Simpler methods exist, such as regular or gel Super Glue, and may be better choices for amateurs.

WOUNDS AND INFECTIONS

Day Three began in the classroom with a lecture on treating abscesses and cellulitis, the two most common forms of wound and skin infections. Cellulitis is characterized by spreading redness, thickness and pain, is usually the result of a bacteria called streptococcus, and treated with drugs like penicillin. With an abscess, on the other hand, one normally sees a localized red lump where the central area dies and turns to pus. Unlike cellulitis, bacteria called staphylococcus and MRSA are the causative agents.

All of these bacteria normally reside on everyone’s skin. Antibiotics will not drain pus, which is a surgical problem. For minor infections, it is best to apply heat packs until the head of the abscess bursts. Incisions may be necessary for larger abscesses, but make sure to drain all the pus out. Pack the wound open and let it heal from within.

Next we talked about different types of respiratory infections such as colds, sinusitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia. All of these may be bacterial, but most are viral. And viruses aren’t treatable with antibiotics; thus the old saying, “There’s no such thing as a cure for the common cold.” In the field, there’s no way to know if a particular infection is viral or bacterial. What to do? If the person looks really bad, give him antibiotics. If you think it’s only the common cold, don’t. Just let the virus run its course. Common medications for respiratory infections are Amoxicillin and Azithromycin.

The next topic was gastrointestinal (GI) infections. We all know the unpleasant symptoms: mostly vomiting, diarrhea and bloating. GI problems can be caused by bacteria, viruses or toxins (think food poisoning). Most cases are self-limiting and the patient will likely recover if you do nothing. The important thing is to avoid dehydration, which is the single most common cause of death among sick children worldwide.

Oral rehydration is the best way to avoid dehydration. Administer clear liquids such as water or sports drinks in very limited amounts at first to prevent the patient from vomiting it back up. On the other end, so to speak, diarrhea can be controlled with prescription drugs like Lomotil or over-the-counter meds such as Kaopectate or Immodium.

KITTING UP

The last topic covered in the classroom was assembling one’s first-aid kit. Gunsite had provided each student with a quality nylon pouch that contained basic tools such as bandages and tourniquets. Now the good doctor supplemented that with his recommendations of which medications should be added. These included meds you take regularly, especially prescriptions such as insulin for diabetics, Dexilant or other proton pump inhibitors like Nexium and Prevacid for acid reflux, and cholesterol medicine.

SIMS ammo is classified as non-lethal, but at close range it can cause painful bruises and blood blisters. Author took one for the team.

THE SIMS FINALE

The final event was another SIMS exercise. This one utilized a gully that represented a city street leading to a riot that had left victims along its path and with the rioters apparently returning along the same route ready to commit further mayhem. Each student was given a SIMS pistol and assigned to treat victims with random injuries that were modified from student to student. Participants were required to diagnose, triage and treat victims as appropriate to the individual circumstances dictated by the instructors, who also provided intelligence on the rioters, how far away they were, their disposition, etc.

As would be the case in a real crisis, the amount and quality of first aid provided to the victims was mandated by how badly the physical safety of the providers would be compromised by staying and providing assistance. During one drill, the aid provider quickly assessed the situation and determined he would be killed if he stayed, and so elected to evacuate and save himself to fight another day.

Significantly, the instructor heaped praise on the student, stressing the futility of sacrificing oneself for no gain. It sounds harsh, but people don’t come to Gunsite to learn how to host tea parties.

The alleged live fire and frangible ammo drills were related to the only hiccup in the administration of the Gunsite Emergency Medical Preparedness Course. Students were told to bring 600 rounds of live-fire ammo for their handguns and 100 rounds of frangible. Neither were ever used, nor was the reason made understandable, at least to some students who were expecting trigger time, didn’t get any, and were thus disappointed. I must admit this did not bother me at all. I knew how to shoot fairly well already and had come to this class wanting to learn about emergency medicine.

The SIMS drills that were conducted taught the integration of the two, to my satisfaction at least. Since we didn’t get to conduct any live-fire exercises, I took my Glock 19 and case of Black Hills 9mm FMJ home and proceeded to shoot it up as best I could from the compromised positions I had assumed while treating “wounded.” In this way, I tried to make the best of a less-than-ideal situation.

S.W.A.T. readers adapt, improvise, and above all, don’t whine. In the overall picture of the class, it wasn’t a big deal. I mention it for the sake of thoroughness and journalistic integrity. At S.W.A.T., we don’t pull any punches, even with a fine organization like Gunsite.

This is one class (maybe the only class) I recommend to anyone I know, shooter or not. Its application for those who go in harm’s way is obvious, but anyone with an eye on possible future disaster scenarios would be well served by the extensive knowledge to be gained. It’s truly more than just advanced first aid.

SOURCE:

Gunsite

Dept. S.W.A.T.

2900 W. Gunsite Rd.

Paulden, AZ 86334

(928) 636-4565

www.gunsite.com