“Stopping power” is a term that’s familiar to all shooters, particularly those who own and carry guns on duty or for personal defense. In simple terms, it means the likelihood of a particular caliber or round to incapacitate an opponent when he’s struck with it. It also relates to the probability of shutting down an attacker by targeting specific areas of his body. For example, one of the most common “failure-to-stop” tactics is to target the head after torso shots have failed to produce rapid incapacitation.

Although generally associated with firearms and combat shooting, if you really think about it, stopping power is actually the objective of all weapons and tactics used in personal defense. After all, incapacitating your attacker is what eliminates the threat and keeps you and your loved ones safe. Lethality, while a possible by-product of the application of a weapon, is not synonymous with stopping power. If you inflict a mortal wound on your attacker, but he lives long enough to kill you or cause you serious injury, you haven’t accomplished your real goal.

So far, all of this probably makes pretty good sense. It may even seem obvious to you. However, let’s take it out of the realm of firearms and consider stopping power as it applies to the defensive use of the knife.

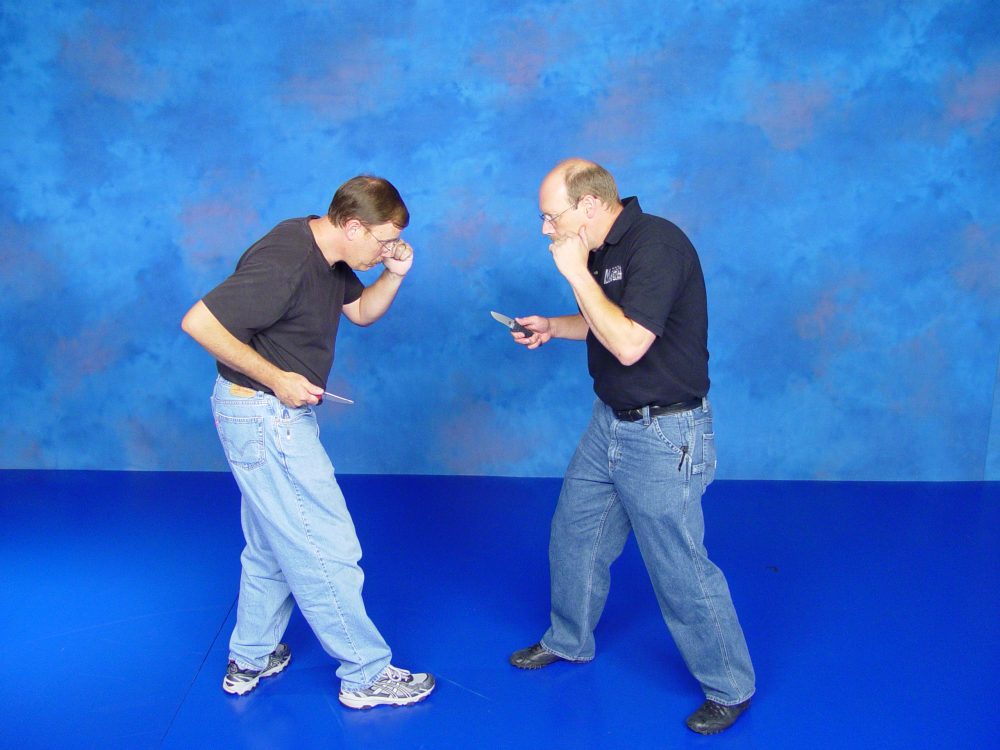

Sequence shows how effective structural targeting can be easily combined into practical technique. Against Mike Rigg’s low slashing attack, author cuts flexor tendons of wrist with forehand cut. He immediately follows with backhand cut to triceps and a check with left hand. This check positions attacker for finishing cut to quadriceps.

Table of Contents

Non-Stopping Power

If you talk to most law enforcement officers, corrections officers, paramedics and trauma doctors, you will hear countless stories of people who have been stabbed—in some cases numerous times—and not only survived, but remained very active during the minutes immediately after they received their wounds. In fact, it’s not uncommon for recipients of stab wounds to not even realize that they have been stabbed and be totally oblivious to their injuries.

Sequence shows how effective structural targeting can be easily combined into practical technique. Against Mike Rigg’s low slashing attack, author cuts flexor tendons of wrist with forehand cut. He immediately follows with backhand cut to triceps and a check with left hand. This check positions attacker for finishing cut to quadriceps.

Although such incidents are both relatively common and well documented, most knife fighting “systems” being taught today still advocate thrusts to the torso as an effective means of stopping someone with a knife. This belief is also regularly regurgitated by the all-knowing “experts” who pontificate on Internet forums. Reality, however, dictates otherwise.

Here’s the bottom line: Stabbing someone in the torso—even multiple times—will not make him burst into flames and immediately cease all hostile action. Cutting the carotid arteries won’t do it either. Even a thrust that punctures the heart is not guaranteed to drop a man immediately.

Sequence shows how effective structural targeting can be easily combined into practical technique. Against Mike Rigg’s low slashing attack, author cuts flexor tendons of wrist with forehand cut. He immediately follows with backhand cut to triceps and a check with left hand. This check positions attacker for finishing cut to quadriceps.

Five Types of Knife Stopping Power

So how do you stop someone with a knife? I have identified five primary types of knife stopping power. Specifically, they are:

- Psychological

- Blood Loss (exsanguination and hypovolemic shock)

- Damage to major life-supporting organs

- Damage to the central nervous system

- Structural stops

Sequence shows how effective structural targeting can be easily combined into practical technique. Against Mike Rigg’s low slashing attack, author cuts flexor tendons of wrist with forehand cut. He immediately follows with backhand cut to triceps and a check with left hand. This check positions attacker for finishing cut to quadriceps.

Psychological

Psychological stopping power is a “stop” that results from either the fear of the knife itself or the fear and shock that result from a wound of any type. Basically, the attacker shuts down mentally, even though the physical damage he suffered, if any, isn’t debilitating. Unfortunately, an attacker’s psychological reactions are highly unpredictable and therefore totally unreliable.

Sequence shows how effective structural targeting can be easily combined into practical technique. Against Mike Rigg’s low slashing attack, author cuts flexor tendons of wrist with forehand cut. He immediately follows with backhand cut to triceps and a check with left hand. This check positions attacker for finishing cut to quadriceps.

Blood Loss

Many knife systems and knife fighting practitioners believe that stopping an attacker is best accomplished by causing massive blood loss. Misguided historical references such as W.E. Fairbairn’s famous Timetable of Death fueled this misconception to the point that it has become legend. While exsanguination (“bleeding out”) can stop an attacker and can often be fatal, in most cases, it does not stop him quickly enough to keep you safe.

For example, Fairbairn claimed that severing a person’s carotid artery (one of the major arteries of the neck) would produce unconsciousness in five seconds and death in 12. Modern medical science, however, provides quite a different scenario. Even at an elevated heart rate of 220 beats per minute (a factor that Fairbairn neglected to address in his statistics), it actually takes an average of 68 seconds to bleed to unconsciousness with a severed carotid artery and 89 seconds to bleed to death. Sixty-eight seconds is an eternity when fighting with deadly weapons at contact distance and hardly qualifies as an effective “stop” in my book.

Sequence shows how effective structural targeting can be easily combined into practical technique. Against Mike Rigg’s low slashing attack, author cuts flexor tendons of wrist with forehand cut. He immediately follows with backhand cut to triceps and a check with left hand. This check positions attacker for finishing cut to quadriceps.

Organ Damage

Many people also believe that puncturing a major life-supporting organ will cause an attacker to shut down immediately. Again, if we consider the number of people who have successfully survived stabbing attacks to the torso, it’s clear that such an approach is not as reliable as we might hope. Also, when you consider the penetration power of the knife and put it in context with the possible physical differences in attackers, many complicating factors arise. For example, a typical tactical folder (the kind you would actually have on your person when an attack occurs, not the seven-inch Randall back home in your sock drawer) could easily puncture the vital organs of a thin, slightly built attacker. However, replace that attacker’s six-pack abs with a 250-pound biker’s pony keg, and suddenly you’re no longer able to reach vital organs with your blade.

Assuming you were able to successfully target your attacker’s vital organs, there’s still no guarantee that he’ll go down immediately. Talk to deer hunters and you’ll hear plenty of stories about perfect shots that punched through both the deer’s lungs and his heart—right before the deer bolted and ran several hundred yards before dropping. Well, give that deer an opposable thumb, a lethal weapon, add a few tattoos for color and you’ve got a hell of a fight on your hands even after you’ve hit him with a killing blow.

Sequence shows how effective structural targeting can be easily combined into practical technique. Against Mike Rigg’s low slashing attack, author cuts flexor tendons of wrist with forehand cut. He immediately follows with backhand cut to triceps and a check with left hand. This check positions attacker for finishing cut to quadriceps.

CNS Damage

As with firearms, targeting the central nervous system—the brain and spinal cord—with a knife is an effective and virtually instantaneous method of incapacitating an attacker. The problem is that hitting such targets in the midst of a stand-up fight is very difficult. Typically, the spinal cord is facing away from you and access to the brain must involve going through the orbital sockets or under the chin.

Sequence shows how effective structural targeting can be easily combined into practical technique. Against Mike Rigg’s low slashing attack, author cuts flexor tendons of wrist with forehand cut. He immediately follows with backhand cut to triceps and a check with left hand. This check positions attacker for finishing cut to quadriceps.

Structural Stopping

The final—and most practical—form of edged-weapon stopping power is structural stopping. In simple terms, this tactic consists of cutting strategic muscles and tendons to destroy specific motor functions. To move a body part, your brain tells muscles to contract. That contraction pulls on tendons—which are like cables—that pull on bones to produce movement. If a muscle is cut deeply enough, it cannot contract properly and the body part will not move. If a tendon is cut, the muscle and the bone are disconnected and, again, the body part will not move. The beauty of this approach is that it produces instantaneous results and can be selectively applied to specific body parts, if desired. A side benefit is that it does not have to result in life-threatening wounds.

Cut to triceps muscle or triceps tendon just above the elbow eliminates attacker’s ability to extend his elbow, severely limiting his ability to wield a weapon.

Historical and Cultural Examples

Although many couch commandos will claim that this approach to stopping power doesn’t work, historical evidence from both Asian and Western sources suggests very differently. On the Western side, analysis of the remains of warriors killed in medieval battles found that in many cases, they suffered a combination of disabling wounds and fatal wounds. In many cases this consisted of a deep, disabling cut to the quadriceps muscle of the thigh, followed by a killing blow to the head.

In Asian fighting arts, most notably the Filipino arts, a fundamental tactic is “defanging the snake”—targeting the attacking limb to destroy its structure and function. According to their symbolism, the weapon is the “fang” and the arm wielding it is the “snake.” Removing the fang from the snake immediately eliminates the primary threat to the defender—the attacker’s weapon—and offers safety quickly. In situations where the application of lethal force is warranted and tactically necessary, it’s also a lot easier to “finish the job” when the opponent is already disabled.

In the traditional Filipino knife arts, defanging is typically accomplished by cutting the attacker’s wrist or forearm. The goal is to sever the flexor tendons that connect the forearm muscles to the fingers, destroying the attacker’s ability to grip his weapon. Cutting the muscles of the forearm can produce the same effect.

Martial Blade Concepts

As a student of knife tactics for roughly 30 years, I have trained in and analyzed a wide variety of Asian and Western knife systems. I have also become a dedicated student of human anatomy and physiology so I can understand the vulnerabilities of the human body to knife attacks. Most importantly, I have conducted extensive analysis of actual combative incidents involving knives, as well as industrial and home accidents involving serious, disabling cuts. The result is a stopping-power-oriented system of defensive knife tactics called Martial Blade Concepts, or MBC.

MBC has three target priorities that were selected based on irrefutable principles of human anatomy established through both research and extensive interviews with victims, law enforcement officers, correctional officers, paramedics, trauma doctors, orthopedic surgeons and physical therapists. These targets—and the reliable, predictable effects of cutting them deeply—are as follows.

Priority Targets

- The inside (palm side) of the wrist. As previously noted, cutting this area offers a high probability of severing the flexor tendons and/or the forearm muscles that power them. This immediately disconnects the fingers from the muscles that enable them to close and grip things—like weapons.

- The bicep and/or triceps muscles of the upper arm. To wield a weapon effectively, an attacker must have the ability to flex and extend his elbow joint. These muscles provide this function. If they, or their associated tendons, are severed or cut deeply, coordinated motion of the arm is severely impaired and the attacker can no longer wield a weapon effectively.

- The quadriceps muscle at the front of the thigh. The function of the quadriceps muscle is to extend the knee joint. That function is what allows us to stand up and support our own weight. It is also critically important in walking, running or any other type of movement. If severed—especially in the first few inches above the knee joint—that leg can no longer support weight and the attacker will literally drop to one knee. This “mobility kill” provides immediate safety by allowing you to create distance and escape.

In addition to offering predictable, reliable debilitating effects, these targets were selected based on the fact that they can be easily and effectively targeted with a small knife. To validate this, I conducted extensive cutting tests on limb-sized targets made from wooden dowels wrapped with pork roasts and covered with multiple layers of plastic wrap to replicate the resiliency of skin. These targets were covered with typical clothing and then “attacked” with the type of tactical folding knives and small fixed-blade concealment knives that you would actually carry for personal defense. These tests conclusively proved that blades three to four inches in length can easily and reliably cut priority targets to the bone and produce exactly the kind of disabling wounds necessary to stop an attacker.

Ease of Target Acquisition

The final advantage of structural targeting is that, in the process of attacking, your opponent literally extends these targets toward you. Compared to traditional targets like the torso, this makes them much easier to hit. Some critics of structural stopping will still claim that it requires surgical precision, but if you compare the surface area of our arm and leg targets with the torso and neck targets they recommend, you’ll see that there really isn’t much difference. Even if there was, the bottom line remains that when our targets are cut, people stop.

Effective knife tactics combine a thorough understanding of human physiology, a realistic grasp of the capabilities of the knife, and natural, easily learned patterns of movement. Properly integrated, these elements offer reliable stopping power. Anything less isn’t worth betting your life on in a fight.

[Michael Janich is a noted edged weapons instructor and author of numerous books and instructional videos. A decorated U.S. Army veteran and former DIA intelligence officer, Janich has also designed knives for Masters of Defense, Spyderco, Combat Elite, BlackHawk Blades and numerous custom knifemakers. For more information, please consult his website, www.martialbladeconcepts.com.]