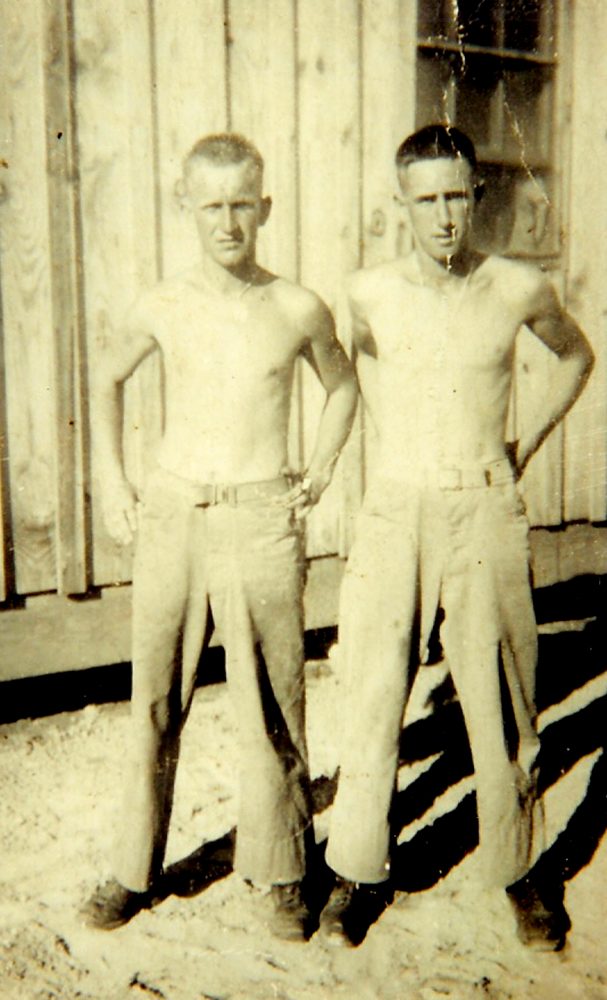

My grandmother—my Bobki—arrived illiterate from Poland when she was a teenager. She married young in a mill town, cleaned houses for income, lost her husband on Christmas Day when she was seven months’ pregnant with my father, and remarried a man who died not too many years thereafter. Between my Dad’s brothers, sisters, step-brothers, step-sisters, half-brothers and half-sisters, there were 13 kids in the small house—three to a bed at times. She never took welfare, and none of her children did, either. Despite exhibiting virtually every one of the “risk factors”—poverty, a single-parent household, etc.—that correlate with drug use, abuse and dysfunction in a family, every one of her children grew up to be a hard-working, productive middle-class citizen, and none of them were ever in trouble with the law. Virtually every one of her grandchildren went to college, and many of them have at least one advanced degree. She is my counter-argument to the assertion that poverty “causes” crime.

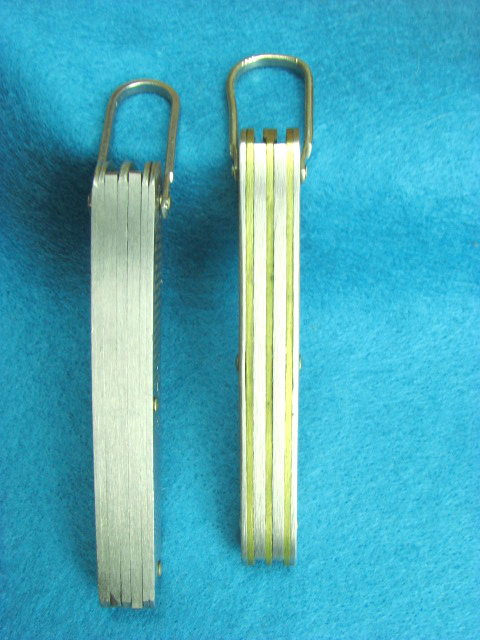

Minor changes and different blade arrangement between original version of Demo knife and current version are readily visible. Knives are set against Japanese Lugar brought back from Saipan by author’s father.

Every Christmas Eve, the entire family—and there are a lot of us—would gather at one of the aunt’s or uncle’s houses. One of the uncles would play Santa, and come in with presents for all. After we grandkids grew up, the tradition continued, and it does to this day, even though Bobki died some decades ago and there are fewer of her 13 kids still alive. Now, my cousin’s son plays Santa to the great-grandkids, and the host always has a little token gift for everyone present. On Christmas Eve of 2004, “Santa” dropped a little package in my lap that was heavier than expected. Inside was an obviously well-worn pocket knife of no rich lineage with the words “U.S. Marine Corps” on one scale. My uncle—the younger half-brother of my father—said, “That was your Dad’s knife in the war. He gave it to me when he returned and I just found it. I thought you’d like to have it.”

Oh, yes. Yes, I would!

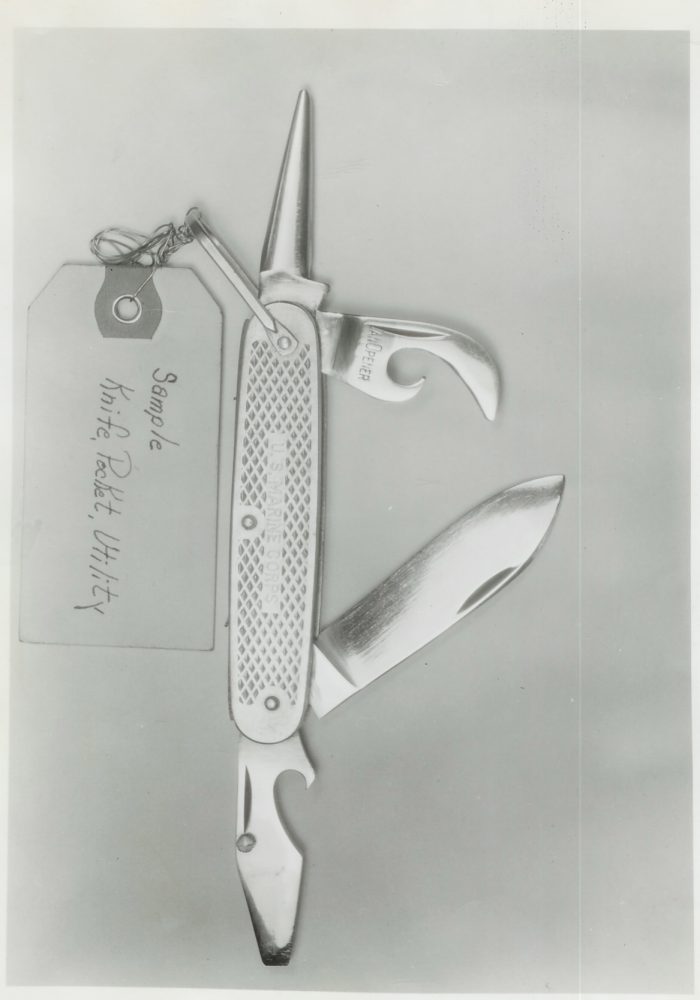

The knife in question is often called the “Demo” knife today because one came with every military demolitions kit—right there alongside the C4. Dad was on the second wave into Saipan, near the end of the war, and he was issued this knife when he was promoted to corporal. It was simply called the Marine Corps knife then, and its blades were made of some sort of undefined, non-stainless steel with brass liners. Between the “U.S. Marine Corps” stamping and Dad’s service dates, I determined that he must have had one of the knives made in 1945—the first year they were produced. They were made by Camillus and Kingston (which was not a real company, but a collaboration between Imperial and Ulster) for a few months in 1945, then the war ended and the contract was cancelled. In 1949, they were again produced for less than a year (this time in all stainless by Camillus), and in 1957 production started again and has continued (in all stainless) ever since.

The formal name for this knife is the MIL-K or “milk” knife, after the military (MIL) knife (K) standard (specifically, number 818) from which it was originally derived. It is produced for both military and civilian markets by Camillus today as the Military Camp Knife. Government versions are stamped “U.S.” on one scale, while civilian versions have been stamped “U.S.,” “U.S.M.C.,” “U.S.A.F.” and “U.S.N.” The last two versions have been discontinued and are not common. The knife was even produced for the Canadian military once with no scale stampings. Versions made since 1949 have the year of manufacture stamped on the base of the main blade, and if you have a 1949 version, you have quite a rare piece.

This knife was born of the military desire to make a less expensive replacement for the bone-handled, shield inlaid folding knives that were previously issued. It was patterned after the common four-bladed utility/camp knives that everyone made at the time, incorporating a 2-1/2-inch spear-point main blade, a can opener, a screwdriver/bottle opener and a punch. It incorporated a then-new can opener design, the downward hooked “birds-head” opener.

Early versions have the main blade and screwdriver on one end, folded to the middle, with the can opener and punch on the other, folded to the sides. Later versions have an alternating folding configuration with the main blade sharing an end with the can opener. Later versions also incorporate a notch in the scale to make opening the punch easier. While this combination of blades is not a “survival” knife in the pure sense (there are precious few cans of food in the wilderness, nor things that are screwed together), it is a true, time-proven “survival” multi-tool in a military setting.

Original versions of the “milk” knife had a 9/64-inch opening stud on the screwdriver. From 1958 to 1972, this stud was 3/32-inch in diameter, and after 1972, the stud was dropped. Much speculation exists about the purpose of this stud, with the best answer being that it is enormously helpful in taking down various small arms of the day (the Springfield 03-A3, the M1 Carbine, and the M1 Rifle).

Over the years the knife has been produced by Stevens, Kingston, Imperial, Western, Case and Queen in addition to the largest producer, Camillus, which alone made about 15 million. It has seen service in every war since WWII, in all military branches, and is still issued today. You can buy this military staple stateside through many retail channels. Its suggested retail is about $21, but it often sells for much less. You can find it at tag sales, flea markets, and second-hand stores. In fact, collecting one from every year of manufacture is a popular activity among collectors.

Older version of Demo knife has stud that is absent today. Its intended function is subject of much debate.

As I was trying to remove some of the rust that had built up over the years on Dad’s knife, one of the rocker springs, fatigued from age, broke. (Hint: Don’t half-open two blades on opposite ends of a common spring. It puts too much pressure on the spring.) I contacted Camillus, and they repaired the knife and also sent me a current civilian version marked “U.S.M.C.” Except for the all-stainless construction and minor changes noted above, they are the same knife. I put the same edge on both the 1945 and 2004 knife blades with Diamond Machining Technology’s coarse and then fine hone. Trying out the cutting abilities of these identical—except for the steel—blades on my standard test mediums, I found that both cut very well. In fact, I’ve had larger fixed-blade knives through here that did not perform as well as either of these very inexpensive tools.

I suspect that this classic knife will still be popular in the 22nd century. If I was a collector, I’d have just set Dad’s knife aside, but no matter what it’s worth (maybe $200), there’s far more value to me in actually carrying and using the same knife my father used in a faraway place in his generation’s war against tyranny. And I hope to pass this memento onto my nephew when he’s of age.

[Author’s Note: This article doesn’t even scratch the surface of information available on the MIL-K knife. If you’re interested, you’ll find a trove of information out there. Thanks to Tom Williams, Camillus company historian, for his generous assistance in researching this article. Frank Trzaska, a well-known military knife historian, was also of great help to me. His highly informative website is http://www.usmilitaryknives.com/. Frank sent me a very thorough article on this knife by Dennis Ellingsen, from the February 1988 edition of Knife World. Don Rearic has a tribute to this knife by Ken Cook on his website.]