Optics have come a long, long way since Y2K. The advances in combat optics have been so fast and furious they can be hard to keep up with. Today’s shooter is faced with such a staggering variety of choices in power, reticle, features and mission applications that it can lead to “paralysis by analysis.”

Unfortunately many shooters don’t have access to the available models, and it is hard to form a useful judgment until the optic has been shot for a while. Worse, the entry price for top-shelf optics often nears or exceeds the rifle, so the penalty for a bad choice is steep. The initial decision is usually based on what zoom range is needed.

My thoughts based upon a few years behind many of the leading-edge models might help with your decision.

Optic defines the use of the rifle. These BCM ARs are similar, but the Leupold MR/T and offset DeltaPoint Sights push rifle to deliberate precision work with close-range backup ability, while Aimpoint T-1 is purpose-built for a fighting carbine.

Table of Contents

FIRST THINGS FIRST

The most important question is how the shooter will predominantly employ the rifle. The rifle/optic combo that thrills when sighting in from the bench may blow when shot in work-a-day mode. The shooter must honestly assess how the rifle will most likely be shot.

This is probably easiest to divide neatly between standing or with hasty support to dynamic targets in one corner, and from prone/deliberate support to distant targets in the other corner. There are more than a few scopes out there that have genuine capability in both roles, but they typically skew in one direction.

Today’s high-end ARs can genuinely excel in both roles as issued with minor tweaks, so the optic often defines the rifle.

Closely related to the level of support the shooter envisions is the range to the target for the bulk of the shots. If 90+% of the shots are to be within 75 yards, pick a red dot and don’t look back. If the envelope extends out to 200 yards, the answer might shift, as it may again if there is a healthy possibility of 400-plus yards.

Shooters love to prepare for the worst case, but in optics this may give you a capability in the 1% case at the cost of some performance in the 90% likely scenario. If you build toward the 90% range envelope, you will be a happier customer.

Many shooters equate how well they shoot from a benched rest or bipod and a high magnification optic like the 4.5-14X Leupold on this FN SPR A5M. Getting the most from an optic requires understanding when and how much power to apply.

MYTH: “MAGNIFICATION WILL MAKE ME SHOOT BETTER”

Sorry. Magnification does not allow the shooter to shoot well. There’s no free lunch. Many shooters are genuinely disappointed to find they shot just as well, or in some cases better, with iron sights or a red dot.

Magnification simply lets the shooter see better. This is often not required for the difficulty of the shot and may prove counterproductive depending on the stability of the rifle.

A shooter can typically shoot very well when the target is appropriately sized to the dot or front-sight post. When the visual situation tips to the dot/post smothering the intended target, the advantage shifts to glass. The magnification permits the shooter to clarify placement.

We all get this, and the universal benched at 100 yards to tiny target experience is the perspective the average shooter brings to the quest for an optic. However, magnification isn’t restricted to the target.

The glass is a middleman between you and the thing getting shot at. So when your heart is pounding and your lungs can’t keep up with the sudden appetite for oxygen, that movement into the rifle is just as magnified as the target is. Not fair, but real.

Optics are a trade-off between power and precision supported and close-range speed. Many are capable in both brackets but tilt to one side or the other. From top: 3.5-10X MR/T, Aimpoint T-1 with LaRue Magnifier, and Bushnell SMRS 1-6.5X.

At 1X the shooter benefits from the illusion of stability. It is really, really difficult to hold the weapon still, but at low power the sight appears still within the target zone as you press through four to eight pounds of OEM trigger. As magnification boosts, so does the awareness that the reticle will not … sit … still! The temptation to snatch the trigger at a “NOW!” moment is mighty. Beyond the grasp of most, actually.

Once the shooter loses the warm embrace of Mother Earth in prone and is forced to go to points of contact in kneeling or standing, the optic’s magnification really starts to affect hits. A simple drill I conducted helps illustrate this.

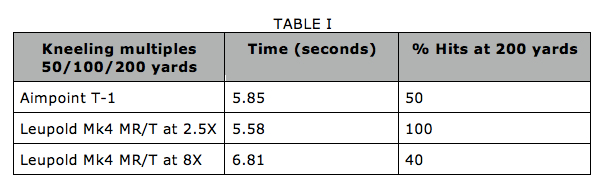

A BCM-4 mid-length rifle with an Aimpoint T-1 and then a Leupold Mark 4 Mid Range Tactical (MR/T) mounted was shot against reduced silhouettes placed one each at 50, 100, and 200 yards. One shot was fired to each target as quickly as possible from a kneeling position at various powers.

The MR/T at lowest power (2.5X) seemed to be the sweet spot in balancing speed and hits from the knee. More power was less on the 200-yard silhouette, being very hard to press the shot through the overly magnified wobble area, which lead to slower times, poor breaks, and misses at 8X (Table I).

From standing, lower magnification such as three-power on low end of 3-18X Mk6 on this M110K1 is key to reducing magnified wobble to get clean hits. Photo: John Jackson

HOW MUCH JUICE?

Not that long ago, 10X was considered a long-range optic suited for sniping. In the last few years, improved loads, rangefinders, and more powerful optics have expanded the engagement window to impressive distances, and the market is full of double-digit magnification choices to 25+ power. But how much “X” does the average rifleman need?

Keep in mind that the higher top numbers drag the lowest power setting up accordingly. It is hard to get beyond 8X and keep a viable low power. Most mid-range optics have a low end in the 2.5-3X range. There is also a weight penalty as the power increases, with the scope gaining weight along with the magnification. Weight is rarely a good thing in a working rifle, so gains need to correlate with needed capability boosts.

As a starting point for frontal silhouette (18×24-inch) type targets, one power for every intended 100 yards of range is not unrealistic for a standing/hasty support rifle. This gives sufficient magnification to place the shot. And 1X/100 yards aids observation and positive identification, but retains maximum field of view (FOV) and minimizes “wobble” from unsupported positions.

Right power for a shot or situation must balance how solid the shooter’s position is with getting aiming point clearly visible while leaving sufficient field of view to maintain situational awareness.

If the shooter wishes to be more capable against smaller targets, such as profile, head/shoulders, shots into loopholes or windows, the starting point may be better at 1.5X per 100 yards, which provides a much better capability for observation and identification.

However, the shooter must work a little harder to stabilize the weapon at this level, since the wobble can become a concern. For example, a shooter wanting to be able to hit down to partially exposed targets (eight to 12 inches) out to 400 yards should consider a variable 6X optic.

For a dedicated from-the-bipod rifle, 2X per 100 yards is not unrealistic. There are newer optics on the market that have an impressive zoom range, such as the Leupold Mk6 3-18X, and maintain a low-power capability. They are definitely intended to be used primarily from support and have the ability to allow the shooter to run 3X up close.

The quality of the lenses in the scope has a disproportionate influence here, leading to the popular term “good glass.” Better quality/clarity allows the shooter to get more done with less power, whereas the milky image in a low-end knockoff might take twice the power to get it done.

Latest generation low-power variables like Bushnell 1-6.5X on this Noveske VTAC rifle represent a new era in do-all optics, with a 1X that approaches a red dot in speed but enough power to identify and reach out to distant targets.

DON’T SLOW ME DOWN

Inside of 40 yards, where a lot of carbine work takes place, any magnification is a handicap, with negative effects increasing exponentially as the range decreases.

Some of the more exciting achievements in optics over the last couple of years have been the hard use, high quality 1-6 and 1-8 power variables that have a nearly true 1X option. Eye relief is still required to pick up the image in the optic, but the shooter sees no apparent magnification and can run the gun within fractions of red dot speed.

The only downsides are that these optics have a little bit of heft to them in ounces as well as dollars. Very attractive low-power options that are compact and light exist in the 1.25-4X range, but there is a slight bobble when looking at even a 1.25X image inside of ten yards. When you step up to 2.5X or more at handgun distances, you are officially fighting your gear and the enemy. This is where an offset red dot or iron sight comes in.

Just as it is wrong to assume that magnification equals better hits, it is also risky to assume that magnification always slows the shooter.

With barricade support, shooter can apply more power to the shot. Great exercise is for shooter to work over support to steel targets at different ranges to gauge ideal amount of magnification.

In the kneeling multiples drill mentioned above, the BCM-4 with Aimpoint T-1 averaged 5.85, or just over a quarter-second slower than 2.5X for 50% hits. There was just too little “meat” of the distant target around the 4 MOA red dot to run at the same speed as the scope showing the reticle comfortably within the target center at 2.5X. Getting certain hits would add even more time.

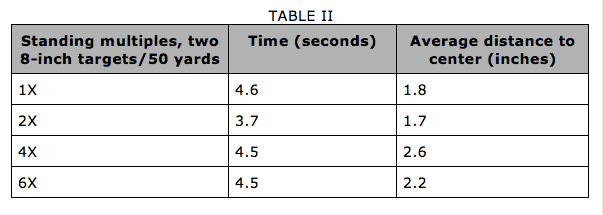

In another drill, I fired the new BCM KMR-13 lightweight upper and a Bushnell Elite Tactical SMRS 1-6.5X against two eight-inch targets separated by eight steps at 50 yards. At the buzzer, the carbine was mounted and one shot fired to each bull as fast as a hit could be guaranteed. The results demonstrate the same principle. Even as close as 50 yards, light magnification boosted speed to a difficult target.

Of course the shooter must be disciplined enough to ignore the slightly magnified wobble and press the shot. But as magnification increased, the quality of the hits decreased. (The 6X average was slightly decreased by one perfect hit that stopped and broke dead center, unlike its kin.) The extra magnification at 4 and 6X shrank the FOV and made transitioning to the next target slower and more difficult (Table II).

Ideal magnification for a given shot in a practical setting must balance power (speed/accuracy of placement) and field of view (speed of acquisition). At 1X, the time gained in transition was lost in dressing up the dot on the challenging target. On a more typical 12- to 18-inch diameter target shot, the speed tilts back to one power at this distance.

Center crops of Bushnell BTR-2 reticle at 1X and 2X to an eight-inch center at 50 yards illustrate how gentle magnification can boost speed to place hits on a tougher target while leaving some FOV to transition to other targets. Unsupported, more magnification beyond this can become counterproductive.

SEEING IS BELIEVING

On several occasions, I’ve had a chance to just work over multiple steel targets at various distances from barricades trying to determine the sweet spots for magnification. I tend to prefer less magnification and will err on the side of too little.

I recently spent an afternoon in this endeavor with the BCM KMR 13 gun and Bushnell Elite Tactical SMRS 1-6.5X scope against eight-inch targets at 100, 150, and a set of three at 200. Interestingly, at up to 2.5X the targets at 200 were not distinct, blending into the background of scrub brush, and the 150 was only faintly visible. The targets were in need of fresh paint but were not camouflaged and were certainly more visible than a prone threat would be.

At 3.5 power, the targets became clear among the brush, but the reticle had to be carefully centered, requiring extra time. At 4X speed, the hits began to pick up, and 5X proved nearly ideal when the rifle was well supported on the barricade, allowing me to rapidly launch Black Hills 77s into the targets. My shooting partner was less comfortable gaining support on the barricade and could only use up to four power, with any additional magnification increasing the image wobble unacceptably.

On any shot with a variable optic, there is a balancing act between enough power to see the aiming point quickly and clearly while keeping the image stable and keeping enough FOV to track movement or quickly drive to other targets.

As a starting point for difficult/distant targets with a variable-power optic, one might consider these “recipes”:

- Standing: 1.5 to 2.5X

- Barricade support: 3 to 4X

- Prone: 4 to 6X

STABILITY MATTERS—A LOT

Stability and magnification are married. The more stable the shooting platform, the more potential benefit magnification can provide. Shooters can mistakenly project how well they are able to shoot a magnified optic from a rest with how they will perform from field positions. That is a well-worn path of frustration. An unstable hold (or shots on the move or a winded shooter) cries out for gentle or no magnification.

This isn’t unique to this particular test. I recently observed a drill at an advanced sniper course where the students had to shoot 200- and 400-meter targets from stepped barricades for time. The best times came from those shooters who cranked the power (and their magnified wobble zone) significantly down from their accustomed magnification when on bipod.

Hitting is all about supporting the gun and pressing the shot in any application. The optic is a powerful tool to enable that shot if the power is balanced to the stability.

SOURCES:

Bravo Company Mfg.

(877) 272-8626

www.bravocompanymfg.com

Aimpoint Inc.

(703) 263-9795

www.aimpoint.com

Bushnell Outdoor Products

(800) 423-3537

www.bushnell.com

Leupold & Stevens, Inc.

(503) 526-1400

www.leupold.com