THE dangerous national trends of de-policing and officers hesitating to employ deadly force trace their origins to Ferguson, Missouri—and Ferguson begins with close-quarters shooting (CQS).

While many have opined on the Ferguson shooting from multiple viewpoints intertwining politics, racism and media hype, few if any have focused on the essence of the matter: the Ferguson fight incorporated an extreme CQS sequence in confined space. The ramifications of this have been largely overlooked or glossed over. But they are profound.

Stripping away the “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” narrative, as well as outright lies, the investigative facts revealed this: An armed uniformed police officer in a marked unit en route to an emergency medical call encountered a robber with a history of violence less than 30 minutes after the crime. The robber aggressively attacked the LEO in his vehicle, trying to grab his gun.

Table of Contents

THE LESS TIME AND DISTANCE, THE HIGHER THE THREAT

First, the lack of distance compressed Officer Darren Wilson’s decision-making sequence. His choices: freeze, flee or fight. Others add more to this survival tree, but let’s keep it simple. Next, the interior of Officer Wilson’s vehicle compacted his bodily options. No room for a lateral step or bladeoff in there.

Third, both the disparity of force and grievous bodily injury justifications for employment of lethal force came into play, via age and body-weight disparity, and because Officer Wilson was unsure if he would retain consciousness if struck in the head again.

Employment of deadly force via his handgun was clearly warranted. Why then was Officer Wilson’s reputation destroyed and career ended?

To be clear, I am not armchair quarterbacking Officer Wilson’s actions. I am offering an alternative to the next officer put in his predicament. That is, after all, a firearm instructor’s ultimate job.

The potential for misinterpretation and the probabilities of racial allegations and political problems come later in the fight, with the shots fired outside the vehicle at more conventional distances. Ergo more efficient CQS could end the next fight sooner and with less controversy.

In 2015, I was honored to be the guest speaker at the International Association of Law Enforcement Firearms Instructors (IALEFI) Annual Training Conference. Having had the opportunity to address for an entire day law enforcement firearms instructors from all over the country and as far away as Hong Kong allows me to say with some surety that while Ferguson’s deadly force incident has redefined American policing, few law enforcement firearms instructors have reacted accordingly.

DEFINITION AND HISTORY

CQS techniques are not part of qualifications, are still only occasionally taught and rarely applied in a lessons-learned format. And yet CQS scenarios are rapidly increasing, not decreasing.

Whether due to bureaucratic inertia, lack of imagination, or fear of accidental range shootings, this must change. But before moving forward, let’s review historical CQS and define it.

Simply put, CQS is a deadly force conflict wherein the shooter’s gun contacts not just his hands but also his body upon firing. Correspondingly, the threat should probably be within arms’ reach of the shooter.

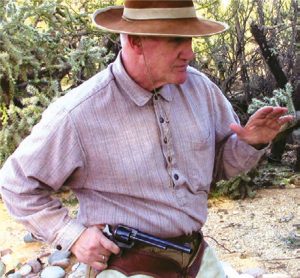

CQS has a long history, beginning in the Old West. Lieutenant John Bourke, fighting Apaches and stationed during the 1870s in my hometown of Tucson, describes in his book On the Border with Crook how Tucsonians disdained drawing and preferred to simply shoot through their pockets!

By the 1880s, the Bridgeport Rig suspended one’s six-gun on a screw between metal brackets on the belt, so for fast close shooting, the weapon simply pivoted up in place from the vertical to the horizontal.

FROM THE OLD WEST TO THE MODERN STREET

Skipping lots of historical interludes, we see modern CQS techniques emerge from frontier gun belts. Early modern CQS involved blading off the body by withdrawing the weapon side and resting the butt of the gun on the hip while the non-firing arm was bent at the elbow and the hand touched the firing-side shoulder. The resemblance to the firing position demanded by Sheriff Flatau’s Bridgeport Rig is striking.

This firing position morphed over the years into a more practical version. Instructors found they were inhibiting the natural draw of the handgun, which would occur by requiring that the gun butt rest on the hip.

Letting the full draw occur at real-time speed, the firing elbow bent completely and the gun came to nestle just forward of the armpit alongside the pectoral’s major muscle. The support hand was moved to cushion the left side of the head from attack, and the left forearm to protect the vital heart and lungs. This was done not to avoid a blow from fist, bat or machete, but to absorb the kinetic energy that might otherwise render the shooter unconscious or dead.

With both of these firing stances, the wrist was meant to be kept straight. There were two imperatives for this. First, a straight wrist reduced possible slide malfunction due to weak-wristing a semi-auto.

Second, the straight wrist allowed a natural pointing upward toward the target’s central nervous system, the idea being that the threat would be so close and so imminent that an immediate one-shot stop was required. It also reduces the risk of shooting through the bad guy and into nearby innocents.

Both these variants were originally meant to cant the gun out at a 20- to 22-degree angle. Because this angle was difficult to achieve, many simply allowed the weapon to turn out at a 45-degree angle. But this angle misses the central nervous system and sometimes even the assailant’s body completely.

Because maintaining the straight wrist when the handgun is tucked against the pectoral is also difficult, some started shooting down into the hip carriage. While safe for nearby innocents, there is no one-shot stop, and the forward momentum of the attacker will carry him into and over the shooter. An ISIS machete wielder would still chop one’s head off.

The technique was further watered down by speed rocking backwards, as first performed by fast-draw six-gunner competitors. Action shooters followed suit. The result? The attacker’s mass and momentum bowl over the shooter, who finds himself fighting on his back—a less-than-ideal situation, to say the least.

TECHNIQUES, TACTICS, AND PRACTICES

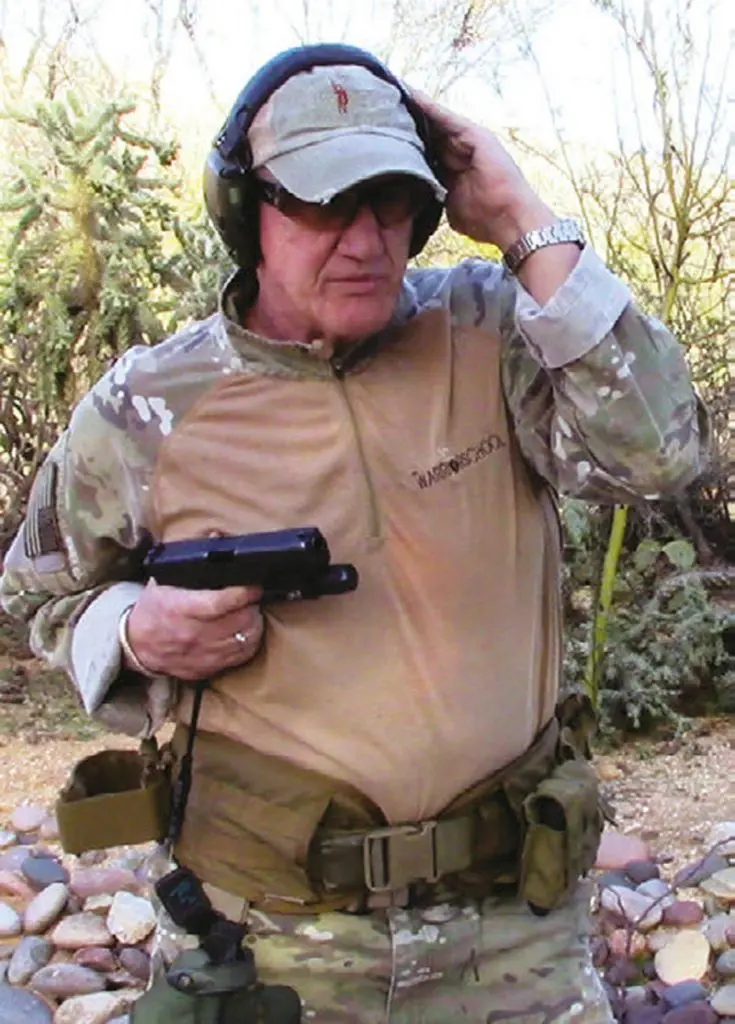

I have never trained action shooters or fast-draw competitors. But I have trained law enforcement, military, and intelligence gun operators by the thousands, usually in five-day courses.

For CQS to be effective, that is to shoot the bad guy while not presenting the gun to him for an obvious gun grab, the gun must be tucked securely at the position earlier described. Blading off the body with the non-firing side negates the gun grab.

Done correctly, this leaves the muzzle just uprange of the shooter’s torso. And I mean just! If he’s had too many doughnuts, the entire position falls apart.

And herein lies the ultimate problem. The non-physically fit and the non-advanced shooter are uncomfortable with firing so close to their vitals. They invariably shove the gun in front of them, thus presenting the gun for an all-too-easy grab by the bad guy.

PRATHER FOREARM

Year after year, student after student, I’ve seen the same thing happen: Shooters extend the gun in front of them to a comfortable distance. So I developed a new way. I humbly call it the Prather Forearm.

The body blades off as before to facilitate an LE interview stance and vital organ protection. The support arm hand hugs the off side as before to ward off grievous bodily harm injury. The handgun is jerked up to the pectoral major position as before. But instead of staying there, the middle, ring, and little fingers of the firing hand are jammed into the non-firing forearm. The handgun slide is snug against the forearm as well. This position achieves the ideal 22-degree upward cant that drills directly into the central nervous system, resulting in the highest probability of an immediate one-shot stop before the ISIS machete wielder can act.

Sights are not used. This is stance-directed fire. Protection is maximized, as is weapon retention. This becomes a very difficult gun grab. The operator need only turn to the right to break the bad guy’s tenuous grab.

An added bonus is that it is an easy transition to a high-ready two-handed isosceles lock. The reverse is also true. From the forearm hold, it’s simple to pull back to a collapsed low ready (safety circle) or high ready. Most importantly, shooters who are less fit and familiar are comfortable and able to perform CQS from this position.

Police pistol practice must become more protean, especially in regard to CQS. Anything less is a failure to train our finest to their best.