Tactical Night Vision Company (TNVC) has brought to market a stunning new technology called the Battleview Infrared Vascular Trans- Illuminator. This device gives tactical medical operators the ability to gain intravenous access under conditions of total darkness.

For those not in the tactical medical field, the magnitude of this development may not be immediately apparent, so let’s expand on the problem this device solves before we talk about the hardware itself.

Table of Contents

IV ACCESS

There are many reasons why having intravenous access is useful—to replace lost fluids or blood, administer medications, or obtain blood for laboratory analysis are just a few. In fact, when providing emergency medical treatment, there is hardly a situation where having intravenous access isn’t superior to not having IV access.

However, the problem is this: it may not always be tactically sound to try to obtain IV access. Even more basic than that, sometimes just finding a vein is difficult, even in controlled environments.

Getting intravenous access and starting an IV is a potentially laborious process. Once you have the basic skills, it can be a straightforward task. After determining the need for IV access, you assemble the necessary equipment, find a suitable site on the patient’s extremity to puncture an identifiable vein, enter the vein, ensure you’re in the vein by seeing blood return through the catheter, advance the plastic catheter, remove the needle, attach the catheter to the IV tubing, and start the fluids running.

Simple, right?

Gaining IV access on healthy individuals is a relatively simple task. Doing so on elderly, chronically ill, obese, or fluid-depleted patients can be difficult or next to impossible by ordinary techniques.

For our purposes, we are concerned about treating the wounded operator. The reason we are trying to gain IV access? He is leaking. Blood. He is entering a state of shock from blood loss, and saving his life depends on our ability to stop the leaking and at some point start replacing those lost fluids. This is not the same as starting an IV on your healthy buddy in training.

When there’s a lack of blood, the vessels that you usually find without difficulty suddenly disappear. You can’t see them through the skin and you can’t feel them. The wounded person’s normal physiologic mechanisms kick in to further constrict all the peripheral vessels in an attempt to shunt blood from the limbs to the central body in an attempt to help keep the brain alive.

In other words, the person on whom you absolutely need an IV is the person on whom it is the most difficult to obtain.

COMBAT IV ACCESS

Now let’s add another dimension of difficulty—the tactical situation.

The scenario is this: our dismounted team has taken small-arms fire from a close distance of under 100 meters in a built-up region on the outskirts of a small town. Multiple fortified buildings provide areas of both cover and concealment.

There are several hostiles engaging us. One of the team is wounded, in the open, and unable to return fire. We’ve identified the source of the fire and have directed massive fire by the whole team against the enemy. Once we’ve achieved fire superiority, we drag or carry our casualty to a position of relative safety.

We have the ability to identify the patient’s source of bleeding. It’s a significant extremity wound with bright red pulsatile bleeding coming from his mid thigh. We do not hesitate to locate the casualty’s own tourniquet that he carries on the midline of his gear for easy identification, and place it to stop the bleeding. When we extricate him to a location with cover, we continue to identify and treat any other potential life-threatening problems.

We’re currently in a location with hard cover in multiple directions. The tactical situation has improved, the source of enemy fire has been eliminated, and while we have achieved fire superiority, we are by no means in a safe environment.

It is possible to proceed to a tactical field care phase, but threats still exist. We are informed that evacuation will be significantly delayed. Assessing our casualty’s vital signs, we note his blood pressure is dropping and his pulse and respirations are increasing. He’s talking, but weakly. He’d already lost a lot of blood before we placed the tourniquet.

The assessment: he is in shock from blood loss, and the need for intravenous fluid resuscitation and volume expanders is obvious.

Oh, did I mention that all this has occurred at night?

The problem with providing medical care at night is the same magnitude of problem as is fighting at night. The major problem with treating a casualty at night is, it’s at night. Enter TNVC and the Battleview.

TNVC BATTLEVIEW

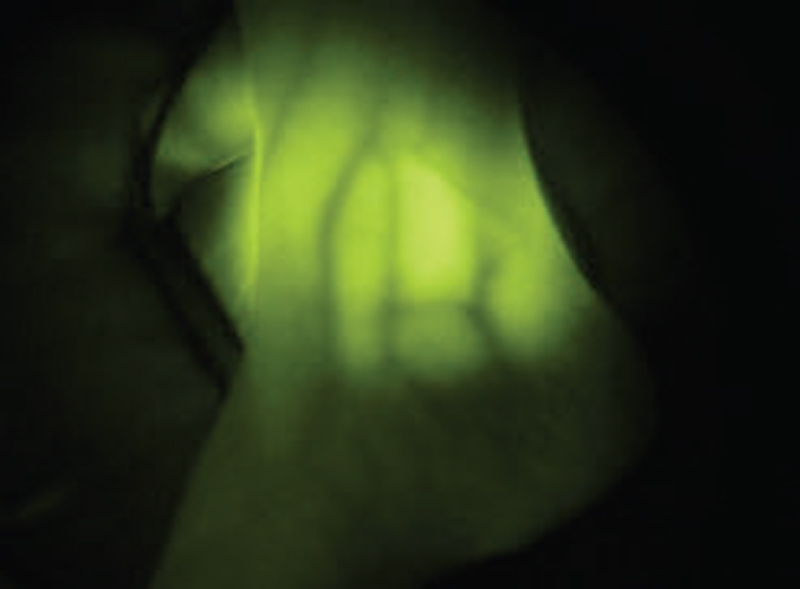

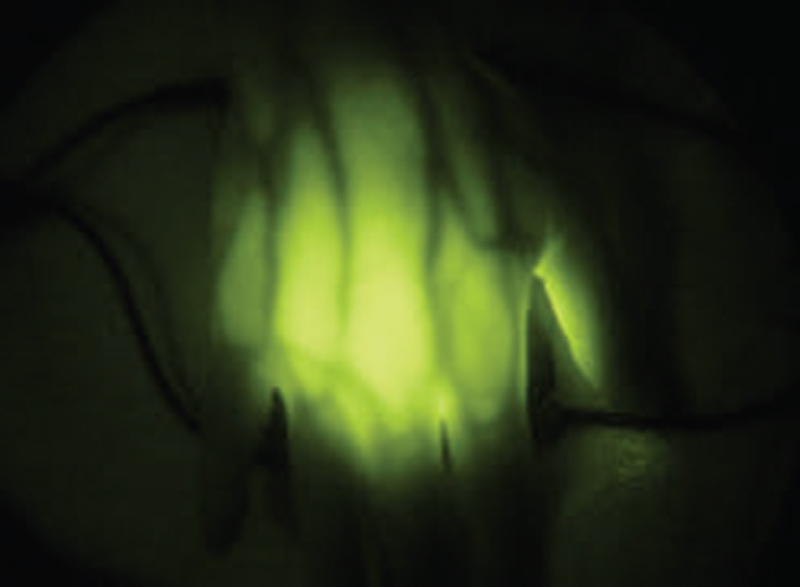

The Battleview is a revolutionary technology that allows us to actually see the veins we’re trying to access under night-vision devices while maintaining complete visible light discipline. It is an infrared trans-illumination device that essentially backlights superficial parts of distal limbs like the hand, wrist, foot and ankle, to allow us to actually see the veins and greatly increase our chances of successfully starting an IV.

In a fit person, the ability to see and even feel the veins distended on the back of the hand, wrist, forearm and elbow crease is pretty common. Even in the region of the ankle, you can often find a vein by sight or touch. How about being able to see the entire course of all the veins like a roadmap, especially the ones you can’t see or feel at the surface? That’s what the Battleview achieves.

Trans-illumination to gain IV access is a technique frequently used in pediatric medicine. A bright light held under a child’s wrist in a darkened room is a useful technique to improve visualization of a vein. It seldom works in adults, as our tissues are too dense. The Battleview negates this problem.

The Battleview has four IR bulbs arranged in a radial fashion and contained in a padded package barely bigger than a pack of playing cards. It is powered by a single 123 battery. It easily fits in a pocket or any small pouch in your aid bag.

EMPLOYING THE BATTLEVIEW

It’s simple to use. Place it behind the extremity where you would normally be searching for a vein. With a little tweaking of its position, the veins in the distal extremities become obvious, like a road map.

For those familiar with IVs, you know you are in the vein when you can see the blood return into the chamber of the catheter needle. With practice, the blood in the “flash” chamber is visible under the illumination of the Battleview.

Focal distance becomes an issue. Map reading distance is about the same as what you need for fine motor tasks like starting an IV. I have found that a close-focus flip-lens is very handy, because it brings the closer plane of focus into clarity in a rapid manner and then by flipping the lens up, returns your focal length to a farther plane. Otherwise, continually refocusing the objective lens of your PVS-14 is necessary. Prepare all the necessary supplies for the IV process and have them close to you and accessible with one hand, just as in daylight.

What you don’t see well under NODs is blood outside the body. There is inevitably some blood spilled during the vein access procedure and, like all liquids, it runs downhill. For that reason, I keep my Battleview in a Ziploc bag when using it to start IVs. It’s a lot easier to clean or replace the bag than cleaning the Battleview itself. (Ask me how I know this….)

At EAG Tactical, we’ve demonstrated the capabilities of the Battleview at our classes and have allowed a wide variety of military, law enforcement, and civilian students to experiment with the device.

For fun, I’ve taken it to the operating room and let some of my anesthesia and vascular colleagues use the Battleview with my PVS-14s. Doctors—especially surgeons and those who work in the operating-room environment—are accustomed to working with high-tech, high-dollar equipment. Anyone’s first experience with night-vision technology is a memorable experience. Adding the dimension the Battleview brings is something else entirely. It is an understatement to say that all have expressed amazement.

FIELD SOLUTIONS

I’m not suggesting the Battleview is a complete problem solver. The veins it allows us to access in the arm are not necessarily the “best” veins. The larger veins in the antecubital region of the elbow crease (the soft region at the front of the elbows where the arm bends) are still the best go-to for IV access in trauma—a place the Battleview may not illuminate.

However, starting one or several IVs in smaller veins to get some volume expansion in a person, and later starting another IV in a larger vein (that is now more visible because I was able to get some fluid into the person’s system) are obviously good things. The reason is because the remaining option is to do a more invasive procedure to gain vein access, such as place an intra-osseous needle in the sternum, or perform a venous cut-down, a surgical procedure where you must open the skin to search for a vein. Even so, the Battleview would aid that process.

The Battleview has so far been successful in every attempt to allow me to visualize the Greater Saphenous vein at the ankle. This vein is the most common site where we routinely perform a venous cut-down when all other methods to gain IV access have failed. The Battleview allows visualization of the vein without the incision. This will greatly reduce the primary complications we see from that procedure—wound healing problems and infection.

The Battleview is a powerful tool. I carry it in my aid bag full time. Even when not using it to trans-illuminate extremities to start IVs in conditions of total white-light discipline, I prop it up on the bag and use it as an IR illuminator to see the small items in my bag or evaluate a patient while under NODs.

Now that I’ve used it for several months, the question presents itself, “Is it actually easier on some people to get IV access with the lights off and using the Battleview than under bright white lights?” On some people and in some situations, it actually is. The implications of this are powerful for what TNVC may be able to offer to the medical field as a whole.