“A BZO (battlesight zero) is the sight settings placed on your rifle for combat. In combat, your rifle’s BZO setting will enable engagement of point targets from 0–300 yards/meters in a no wind condition.” Marine Corps Reference Publication 3-01A, Rifle Marksmanship

“Battlesight zero: A sight setting that Soldiers keep on their weapons. It provides the highest probability of hitting most high-priority combat targets with minimum adjustment to the aiming point, a 250 meter sight setting as on the M16A1 rifle, and a 300 meter sight setting as on the M16A2 rifle.” Department of Army Field Manual 3-22.9

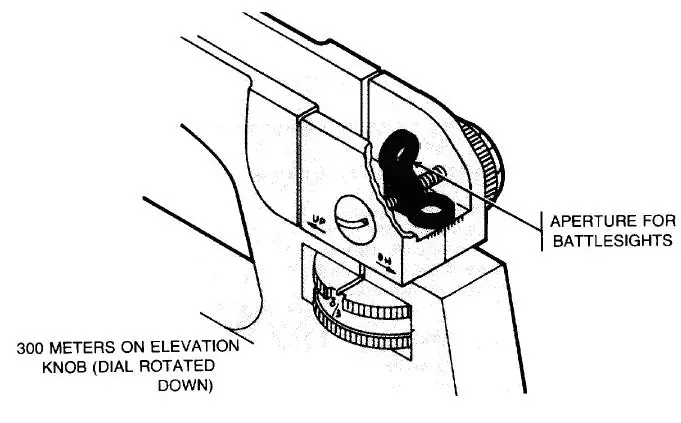

When battlesights are on your rifle:

a. Front sight post and rear sight windage knob are adjusted so you can hit your point of aim at 300 meters.

b. Unmarked aperture must be in the up position.

c. 300-meter mark is aligned with mark on left side of receiver. (U.S. Army TM 9-1005-319-10/USMC TM 05538C-10/1A)

Per both the Marine Corps and Army field manuals, a proper battlesight zero will allow a Soldier or Marine to engage an enemy threat without adjusting the elevation of their iron sights from point blank range or zero yards/meters out to 300 yards/meters. Note that the Marine Corps teaches and uses yards and the Army teaches and uses meters. For edification, 300 yards is roughly 274 meters and 300 meters is roughly 328 yards. A 300 yard/meter BZO makes sense for most combat situations. However, the Army and Marine Corps differ in how to set the BZO on a rifle or carbine. To add even more confusion, numerous well-known shooting schools and private trainers teach a different method for placing a proper BZO setting. Additionally, a certain special operations unit advocates and teaches a 100-yard zero. Who is right? Which method is best? Why?

To answer these questions and others, we need to address some of the myths and misconceptions floating around regarding the proper battlesight zero to place on a Soldier’s or a Marine’s M16A2/A3/A4 Rifle or M4A1 Carbine’s iron sights. We are only going to address iron sights in this article.

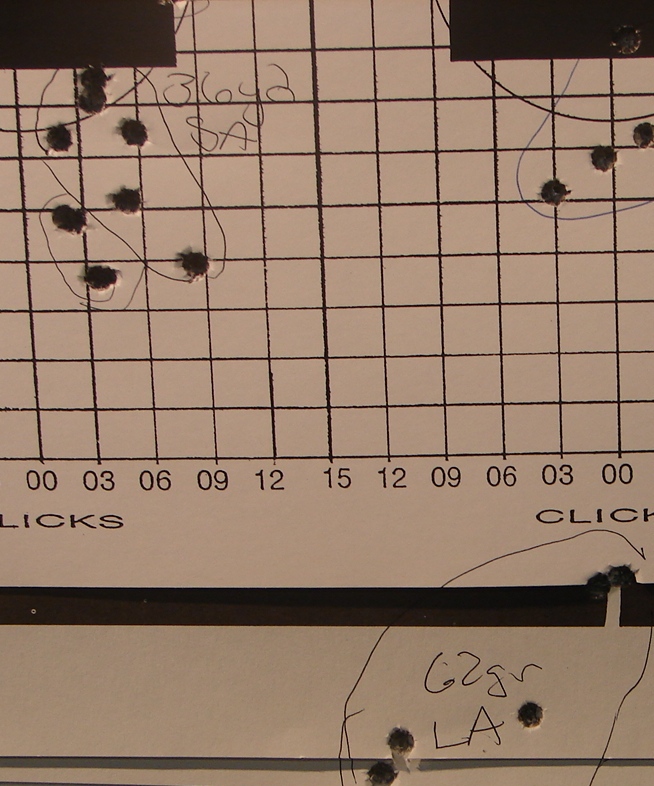

In theory, flipping up large aperture (left) will give shooter 200 yard zero. Author’s testing showed this theory to be a myth.

The Stoner family of rifles and carbines have been with the U.S. military and some of our allies for over 40 years. While not without its problems, it has proven itself worthy on numerous battlefields around the world. We need to consider what might be the best method to BZO these firearms given a particular mission parameter, taking into account ballistics—both terminal and trajectory—of the 5.56mm round in relation to a proper BZO.

Sgt. Dean Caputo, Arcadia, California, PD, shooting M16A3 on Arcadia PD’s excellent 50-yard indoor training range. He was kind enough to assist us during this testing, as well as allow us to use his department’s facilities.

Both the Army and the Marine Corps teach that the maximum effective range of the M16A2/A3/A4 is 500 meters on a point target (individual enemy) and 800 meters on an area target (e.g., troops in the open). Part of the Marine Corps’ known distance qualification course is engaging a stationary black “E” Silhouette (human shaped) target 23.5 inches wide and 39 inches tall on a white background with 10 rounds at a distance of 500 yards from the prone position. It is not uncommon for Expert rated Marines to hit 10 out of 10. This is a great test of basic marksmanship and gives Marines confidence in themselves and their weapon. However, on a battlefield seldom does the enemy remain stationary or perfectly silhouetted at a known distance, nor is the Soldier or Marine always in a stable prone or sand bagged position. Furthermore, on an asymmetric battlefield like Iraq, the rules of engagement may not allow you to shoot at a potential combatant if you can’t positively determine that they are a threat. Five hundred yards (or even 300 yards) is a long distance to pick out camouflaged combatants and determine their intentions without a quality optic. Finally, we have to consider what the lethality of the 5.56mm round is at those distances.

Extensive testing done by the Department of Defense Subject Matter Expert (SME) Ballistics panel recently concluded that besides proper shot placement, the biggest aspect of producing lethal wounds was the yawing and fragmenting effect of the round when it impacted soft tissue. This requires a velocity above 2,500 feet-per-second (fps), preferably above 2,700 fps, for M193, M855 or MK262 Mod 1 ammo. This equates to a lethal range of approximately 200 meters with a 20-inch M16A2/A3/A4 rifle or 150 meters with a 14.5-inch M4A1 carbine. That is not to say that a shot beyond that range will not be lethal, only that the probability begins dropping dramatically. As an example, at 500 yards the velocity of the 5.56mm rounds is approximately 1,500 to 1,700 feet per second, which is equivalent to the muzzle velocity of a .22 LR Hyper-Velocity round. Can you kill someone at that distance with a 5.56mm round? Yes. There have been Marines and Soldiers who have done so during our present conflict at that distance. However, the likelihood of inflicting a lethal wound with a 5.56mm round is significantly diminished past 200 meters.

Okay, so DOD ballistics SMEs have established that 200 meters is probably the maximum lethal range for the 5.56mm round on two legged critters. Now let’s look at terminal performance and trajectory of the various recommended BZOs.

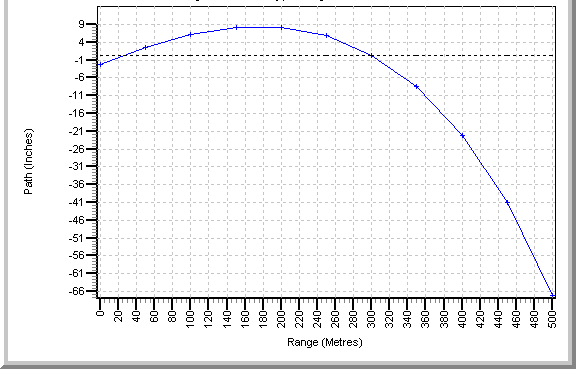

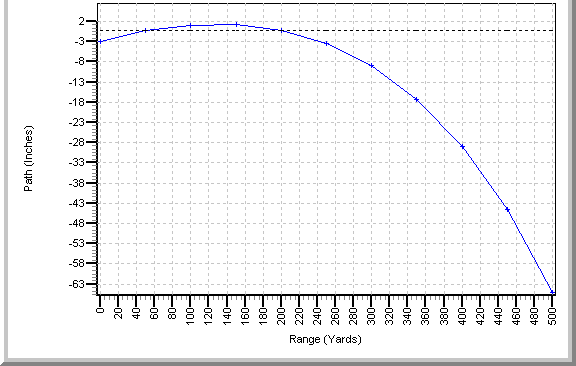

First, there is the Army’s recommended 25/300 meter BZO. This BZO calls for the zeroing of M16A2/A3, M16A4, and M4A1 at 25 meters with the setting of the rear elevation at 8/3+1, 6/3+1, and 6/3 respectively using the small (long range) aperture. The standard is for the Soldier to shoot a 1.5-inch group at 25 meters as the Army extrapolates that a Soldier will then be able to shoot a 19-inch group at 300 meters. Once this standard is achieved, then the rear elevation setting is moved to 8/3 or 6/3. However, the trajectory of the rounds does not seem to have been considered when the Army chose the 25/300 meter BZO, because the maximum ordinate during flight rises almost nine inches above the line of sight around 200 meters. In keeping with the Army’s standards for shooting groups (1.5-inch groups), this could place shots 13 inches above line of sight at 200 meters. Thus, if aiming at the enemy combatant’s chest, Soldiers would shoot high (head and neck area) between 150 to 250 meters with little room for error regarding windage. (See Graph 1.)

GRAPH 1: U.S. Army recommended 25/300 meter BZO.

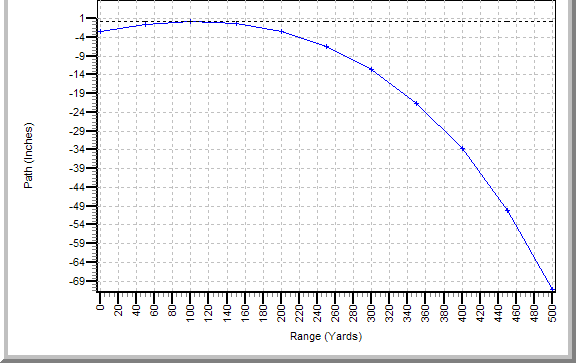

Second is the Marine Corps’ recommended 36/300 yard BZO. This BZO calls for zeroing the M16A2/A3/A4 and M4A1 at 36 yards with the setting of the rear elevation at 8/3 and 6/3 using the small (long range) aperture. This provides a trajectory with a maximum ordinate during flight of just over 4.5 inches above the line of sight at around 200 yards. Thus, with a standard of 12-inch groups at 300 yards, this would allow for most rounds to impact roughly nine inches above the line of sight. With an aiming point on the enemy’s chest, the rounds would land high on the upper chest just below the neck between 150 and 200 yards. This BZO will allow more room for error on the part of the shooter. (See Graph 2.)

Graph 2: Marine Corps recommended 36/300 yard BZO.

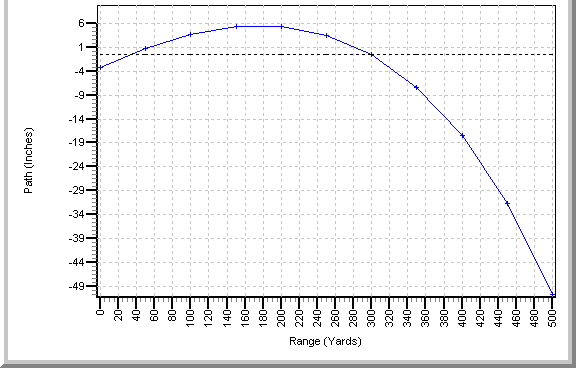

The BZO that is most common with the better-known shooting schools and instructors around the country is the 50/200 yard zero. This BZO calls for zeroing the rifles and carbines using the large (0-200) aperture with the rear elevation set at 8/3 or 6/3. This zero provides a very flat trajectory with a maximum ordinate of just over one inch between 50 and 200 yards. Thus, when aiming center mass with a 12-inch standard at 300 yards, one could expect that most rounds will impact within 4 to 5 inches of point of aim out to 250 yards. After that the trajectory drops fairly quickly, with rounds impacting six inches below line of sight minus shooter error and 12 inches below with shooter error at 300 yards. However, 12 inches below the center of the chest still has rounds impacting in the blood-vessel-rich lower abdomen and groin area with more room for error regarding windage. (See Graph 3.)

Graph 3: 50/200 yard BZO.

A less common BZO, but one used primarily by an elite U.S. military special operations unit, is the 100 yard zero. This BZO fits their particular mission profile, as they typically perform direct action missions that may require them to make very precise shots on threats out to 100 yards, but then immediately transition to close quarter battle actions inside enclosures. The 100-yard BZO is good for threat engagements inside 200 yards, but the trajectory drops off very quickly past that distance. (See Graph 4.)

Graph 4: 100 yard BZO.

One last interesting tidbit to throw into this equation is from the Army and Marine Corps Technical Manual (TM) for the M16A2. Per this TM, one is led to believe that if a Soldier or Marine were to zero the M16A2 (and assuming also the A3/A4 and M4A1) at 300 yards or meters using the small (long range) aperture and then flip up to the large (0-200 short range) aperture, he would have a 200 yard/200 meter zero.

We recently tested this TM theory. Like most theories that look good on paper, they often don’t stand up to field testing. We found that not only were the two zeros not the same, but on average the large aperture groups were six inches low and three inches to the right at 50 yards. If we extrapolate this information out to 200 yards, the shot groups would be 24 inches low and 12 inches off to the right. In essence, shooters would miss their intended targets entirely. When testing this TM “theory,” we knew that we would see a difference in the elevations because the centers of the small aperture and the large aperture are not on the same plane, differing as much as six minutes-of-angle, with the small aperture shooting higher. What did surprise us—until we thought about the mechanics of the rear sight—was the shift in windage. Since the rear aperture rotates on a threaded screw, when it is rotated from small to large, it will move slightly to the right, thus shifting the impact of the rounds to the right.

So which BZO is best? In my humble opinion, it is the 50/200 yard zero for most situations. However, mission, enemy, troops and terrain often dictate particular requirements. Thus, a 25-meter or 36-yard zero may meet your requirements. If I were a private citizen or law enforcement officer, I would zero with the large aperture at 50/200 yards and leave my sights alone, as most defensive (or even offensive) shots required by citizens or patrol officers will be well within 200 yards. However, as an infantryman in the open mountain ranges of Afghanistan, I would consider the 36/300 yard zero with a small aperture, using the large aperture inside of 100 yards (e.g., clearing small villages) when necessary. On the streets of Fallujah or Baghdad, I would prefer the large aperture zeroed at 50/200 yards.

In the end, information is power. When a Soldier or Marine is informed in regards to tactics, techniques and procedures that are currently being used, they can make better decisions to take down the enemy.