The concerto of sound echoed from a mere three feet; the reverberation rose as an old familiar friend. From the first shooter down, it resonated across the line, rising, reaching its crescendo just past the halfway point. Then lessening until the sound of silence brought forth its powerful realization—we were training gunfighters.

A static turn to the right was followed by a non-standard response (NSR: firing more than two rounds) in a Wave of Death, as one shooter after another turned to address their target from the seven-yard line—and in turn rained a torrent of 5.56mm projectiles at cardboard silhouettes in rapid fashion.

This is Pat Rogers’ favorite training exercise. He can’t conceal the wry smile that sweeps across his affable face as the backpressure from a dozen carbines set on fast pushes the air around us. You just know he’s having fun.

Table of Contents

WAVE OF DEATH

The Wave of Death is not an exercise in ballistic excess. It is a training instrument taken from the tool bag of a lifetime of learning, and one that offers a multitude of lessons. Technique notwithstanding, the first two and most important are:

- Gunfights are usually dynamic affairs, hence the need to move or turn.

- Bad guys often require a copious amount of lead to cease and desist their violent intentions.

An NSR is delivered when a person is close and can hurt you. Fear is a great barometer. If I am afraid, I will step on the trigger until I am no longer afraid. So we turn and deliver controlled fire into the center mass of the target until our safety is assured and our fear is gone.

The class had started earlier that day with a 50-yard prone for zero on the carbines, then we worked the range hard from the three- to 50-yard lines. When shooting close to the target for the first time, the most difficult lesson is getting students to understand the principle of holding a mechanical offset between the sights/optic and the intended target at close range—25 yards and in. Once understood and the transition mastered, the class was rocking, lessons shared and absorbed, and the tools and skills passed on for each shooter to perfect at his own pace.

Truth be told, a couple of days on a square range do not make anyone a gunfighter. A structured class like the EAG Tactical Carbine Operator Course teaches skills that a shooter should then develop on their own, with others or in future classes. I was co-instructing this class with EAG owner Pat Rogers.

But this was no ordinary EAG Carbine course. This one was designed specifically for a group of students whose business is black rifles.

BCM ON THE LINE

The entire staff of Bravo Company Manufacturing (BCM) was stretched out across the firing line. No one was at the office building rifles that day. The good news was that we had a whole bunch of gun mechanics if we needed them. The better news was that we wouldn’t—they were all shooting BCM carbines.

Paul Buffoni, CEO of Bravo Company, has a level of commitment on a higher plane. It is evident in everything, from the products he develops to the rifles he builds and the manner in which he runs his company. His attention to detail and tenacious drive separate both Paul and BCM from the competition. Paul’s directive: Everyone, from the accounting department to the shipping department, is a shooter. Life at Bravo Company makes more sense that way.

A unique perspective is to have a shooting student who understands the dynamics of the carbine so well. Having a whole line of them was amazing. A tweak here and a stance adjustment there, and we had everybody shooting where they needed to be in short order.

During the last few years, I have come to expect BCM carbines to run and run. The occasional misstep is usually quickly corrected and the guns are back on the line. Being in this business long enough to witness the evolution of reliability, I can tell you that it is a refreshing way to conduct a carbine class.

FAREWELL TO THE BAD OLD DAYS

A decade ago, the failure rate from the cacophony of carbines that graced our shooting line was appalling. Most guns were put together without the thought of actually shooting them, much less shooting them hard. Parts were substandard, and the understanding of what made a functional rifle was rare.

When I first went looking for an SBR years ago, I stopped at a gun shop in sunny southern Florida. The manager dropped his personal carbine on the counter for me to inspect. It was a lower receiver from a less-than-stellar manufacturer sporting a nine-inch upper from the Acme Gun Company, complete with a bipod, reject red dot sight and big drum magazine.

“You don’t shoot this much, do you?” I asked.

“Not really. How do you know that?”

Some people shouldn’t have a carbine.

But here, now, the carbines ran as they should. When you don’t have to sweat the small stuff, shooting development takes a much more direct pathway. The assimilation of information coupled with skills learned is much more productive.

The shooting day progressed faster than most. We ran two relays, jamming magazines with short hydration breaks, while the BCM crew fought to fill in the extra space on the firing line.

On this first day, we saw a strange assembly of magazines, even though Paul supplied boxes of new mags for everyone. Democratic politicians tend to drive up the value of obsolete carbine magazines, so a plethora of misfits showed up—some good and others of a vintage older than the shooters themselves. Tossing more than a few over the earthen berm to that resting place where tired old magazines go, the problem was eliminated post haste.

BCM FACTORY VISIT

The next day found us at the BCM factory in Hartland, Wisconsin. Humbling is the most apt description that rolls across my computer screen. Humbling in terms of the volume of really cool guns and gear; humbling in the thought process that went into each and every segment of the business of building a fighting carbine; and humbling in the dynamics that make up BCM.

Bravo Company is on the cutting edge of innovation in an industry that can be called plain vanilla by advancement standards. Let’s face it: the rest of the world is building the same old same old, while Bravo Company is leading the charge into developing next-generation battle carbines.

Pistol grips that offer a better angle to the shooter; charging handles that actually offer a handle and don’t self-destruct with hard use; the first truly innovative handguard system in a dozen years; their Carpenter 158 steel bolt assembly—the heart of the AR-15/M16 rifle system. Call me jaded, but I like what I like.

The attention to quality control was obvious from the first few minutes in the building. And therein lies the main reason for BCM’s success. The most radical difference is not just BCM’s ability to manufacture carbines, but the overall care in assembly and quality control. Every part is inspected, tested and held to exacting specifications.

The term balanced and blueprinted springs to mind. In the days of my youth, I was an honest-to-goodness, card-carrying, ether-inhaling hot-rodder. The goal of any wrench turner worthy of the name was to increase performance gained versus dollar spent. The most cost-effective method to accomplish this task was blueprinting.

The rigorous task was breaking a motor down to its basic elements and insuring everything spec’ed out to its most exacting tolerances. Block, pistons, rings, heads, and valves: everything that combines to make an engine scream performance. In the early days of horsepower overcoming weight, this was the secret to maximizing performance.

Acceleration of a mass can be divided into components opposing the direction of travel. In an engine, it is the counter-moving piston causing an explosion in the engine block. In a carbine, it is the bolt assembly igniting a contained explosion with the chamber.

You measure, calibrate, inspect, and examine every part that goes into it. Assemble it with rigorous attention to every detail, well surpassing milspec, and further test and fire every piece. Then you have a recipe for success.

Dynamic balancing of these forces minimizes friction, while the static mass of a very large machine moving slowly would be smooth and not create vibration. The violent action of a six-pound carbine is anything but static when fired, so the real trick is to make it efficient and smooth.

In engine blueprinting and fighting carbine design, all the specifications are double-checked to closer-than-factory tolerances. Holding the carbine to a standard not known within the industry, you have hot-rodder ingenuity in its most fundamental form. And Paul Buffoni is without question a hot-rodder.

ASSEMBLING MY VERY OWN CARBINE

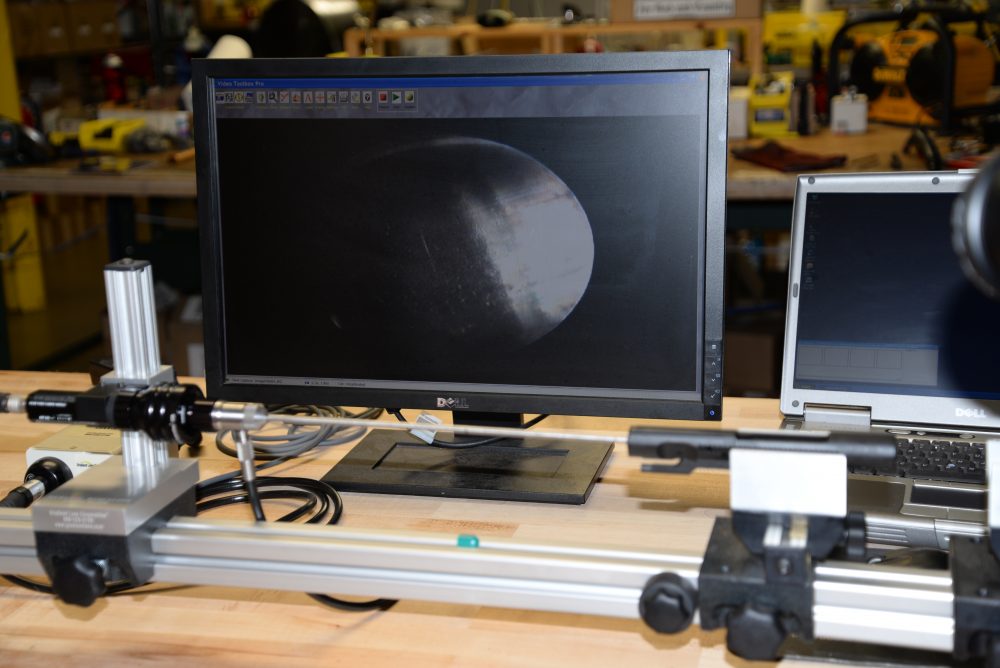

Now it was my turn. I stepped to the bench, and under the watchful eyes of a master gunsmith, I was about to assemble my own carbine. Hardly more than a parts changer myself, this was the first time I’d assembled a carbine with each component fitting precisely with the previous assembly.

I began my assembly process with a clean workbench, six tools and a heat gun. I started with the receiver, then bolted in a medium-weight barrel with KeyMod upper. In much less time than I’d expected, I was running the bolt on a new BCM EAG KeyMod carbine.

Shooting is an ongoing, continuous education. In a business where so-called experts sit at home in overstuffed armchairs and spout nonsense, real shooters and real instructors are students first, and our skills are an evolving science.

As our days with Bravo Company drew to a close, I walked away with a wealth of information learned both on and off the range, and I could not thank Paul and his crew enough.

Goodbyes conveyed, I started the long trek home. But the more I thought, the more I could not resist a quick stop at the range to test out the rifle I’d built. Three magazines later and she was a hot rod.

What else would I expect from BCM?

John Mattera is a 24-year veteran of law enforcement, government contracting and private-sector security. Much of that time was spent training as well as passing training skills onto others, and he has written three books on the subject. John now lives in the Caribbean, where he works in marine archeology.

SOURCES

BRAVO COMPANY MFG.

(877) 272-8626

www.bravocompanymfg.com

EAG TACTICAL

(928) 636-6686 (fax)

www.eagtactical.com