The last couple of years have seen truckloads of new shooters of all ages and backgrounds join the community. Whatever the motivation, these shooters—as well as many established gun owners—are at a point where they are considering attending training. This is outstanding and matches well with the veritable explosion of trainers and schools.

Bottom line: A quality training class is the single best investment a shooter can make and will fast forward the shooter’s ability and learning curve by years. So once the shooter has stopped spending cash on gadgets and is saving for a class, what’s next? I’ve run a number of specialized schools but am at heart a student and have some tips to help the prospective “stud” get the most out of their training.

A class can be the best investment a shooter makes, if the shooter is mindful of certain things as he chooses and prepares.

Table of Contents

WHO, THEN WHAT

The most important ingredient is the instructor. The market is packed wall to wall with experience from all aspects of the gun and its use. There is literally someone for everyone. Plenty of bottom feeders are also looking to cash in on the boom. To minimize risk, the shopping shooter should keep a couple of things in mind as they do the research.

First, focus on the learning. What do you want? Stay close to that and don’t get distracted by personalities, enviable backgrounds, slick marketing, or raving man-crush-holding fans.

As you look at the possibilities inside the corner of the shooting world you want, start by looking through course reviews and after actions. Look specifically for trends. If the trend is a focus on the instructor, be wary. You might be pulled into a high student-to-instructor ratio “concert tour,” where you will be lost in the sea of fans. If the trend is on the excitement or fun of the course, be equally wary. Remember your purpose and go to trade school, not gun camp.

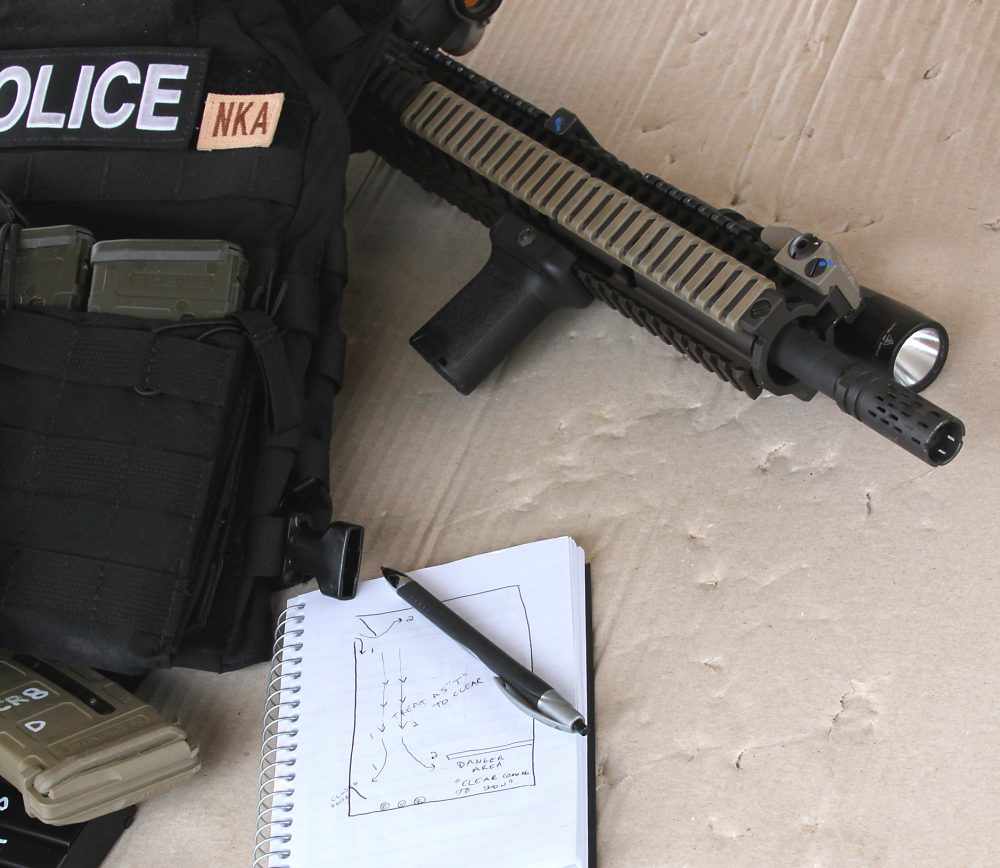

The right instructor is the most important ingredient to a successful class. The market has an unprecedented number of talented teachers, such as Mike S., here at an EAG shoot house class.

If you have a successful baseline and are looking for a challenge to bump you up, excitement may be good. But if the trend keeps coming back to people who are talking specifically about learning and performance improvement … jackpot! Chances are good that they are enthusiastic about their instructor too, but the subtle difference is noticeable.

If you still have trouble winnowing the choices down, consider the student population. Many instructors have a core “following.” Look carefully. You will learn much from the other students in a good class and make beneficial associates. I prefer mixed classes of open-minded serious students. But a relatively homogeneous group is probably good as long as you fit into that particular herd.

If it is a master class, with a hardcore group of steely eyed pros and you show up not ready to match the pace, you’re going to hold the class back or (more likely) get left in the dust and be supervised for safety rather than taught.

If you’re on the bottom rung of the learning ladder, don’t feel like you have to get to the top in one class. A local instructor who is well grounded may be perfect for you if he checks out on the previous criteria.

As you gain experience, you are unlikely to adhere entirely to any one instructor’s style of kung fu, so don’t stress too much about having to agree on every little manipulation technique in advance based on Internet research or debates. Reputable instructors got that way the hard way, over years of classes full of successful students.

Steal back minutes to add into busy training days by refilling available mags and thoroughly checking and prepping all equipment.

PREP TIME

You’ve picked an instructor and secured a place in a class. Now what? These steps, some of which need lead time, will make the class a much higher yield investment.

Hey Buddy

The highest payoff comes from talking a buddy into going with you. Splitting the fuel and lodging costs is the obvious upside, but the real reason is much more valuable. You will struggle to retain more than a small percentage of what is taught. (This will be a theme.) Your shooting partner boosts retention dramatically by the ongoing conversation and slightly different recall of the class.

Subtle but also important, the partner helps bring you into an unfamiliar class environment with at least some level of confidence as you face the unknown together. You are much more likely to ask a dumb (but possibly necessary) question of your buddy than the stranger you just met on the line next to you.

If you’re picking the ideal class buddy, pick one who is slightly more skilled than you but within competitive reach. You will push each other. It is no coincidence that almost every big-name shooter had a solid training partner at some point in their early shooting days. I’ve had several over different duty stations and am immensely grateful for them.

If you have to go stag to class, no worries. Put your big boy pants on, do a quick survey of the class, and find someone to squad with.

Ammo

The early bird gets the worm. Buy quality and buy early. The market is too unstable to lose a training opportunity by waiting to get a better deal or some other procrastination. It’s worth repeating: buy quality. The ammo gods hate a cheapskate worse than a procrastinator, and punish accordingly.

Protecting the hands is key in a high-round-count class. Wear shooting gloves such as the SKD full dexterity model, or mask checkering and sharp edges with tape.

Camera

The proliferation of video cameras has been a huge windfall for students. I learn better by seeing third-person video of my shooting than point-of-view footage of downrange, but both are valuable. If you own or can arrange to borrow a camera, it will help you sort through what really happened when the adrenaline hit and time got distorted.

It’s helpful to plan how you’re going to film and be familiar with the camera’s operation and how you have it rigged and mounted. Otherwise the training value of having a replay option is drained by the loss of teaching points as you monkey with the camera trying to get it set properly rather than focusing on the instruction.

SET A BASELINE

Regardless of your skill level, try to establish a baseline before heading to class. A baseline should address both speed and accuracy. For example, at the true beginner level, it might be the time it takes to push the pistol out from ready and get two hits to an eight-inch target at seven yards. For the more experienced, it might be drills relevant to the pistol or carbine usage. This will help when comparing performance after class.

Proliferation of video cameras has been a huge learning boost for shooting students, enabling instant replay of and better perspective on the actual performance.

GOALS

Before the class, set performance-oriented goals. “Learning a lot” is not a performance goal. “Gain speed on the pistol presentation” is, along with any other specifics you want to learn or improve. For the more experienced, “being high shooter” is an outcome rather than performance-oriented goal. You can control performance goals. Outcomes happen as a result.

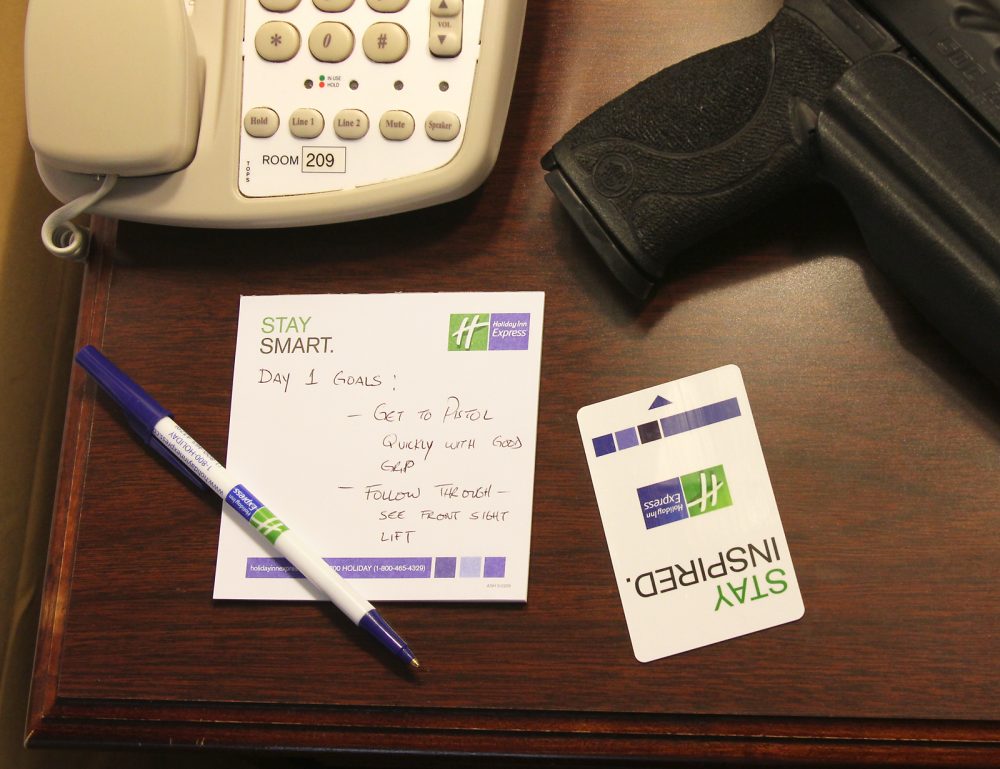

I suggest you clearly write the goals, review them at the midday break, and recalibrate toward them so as not to get caught up in the drills or conversations and not make the progress you intended in an area.

For a beginner, it may be the second day before a more specific performance-oriented goal is possible, once the instructor gives you needed corrections that require conscious effort to perform and ingrain. On the off chance that the class is not as informative as you had wished, having pre-set goals will help enhance the value of the drills and repetitions that you conduct during the course.

Setting clear performance goals before class and keeping focused on them throughout helps student get even more out of the experience.

PREPPING (NOT THAT KIND)

The class is days away. Without being overly dramatic, the final prep phase makes a significant impact on how much you learn. Time is a limited resource, and once class starts is not the time to find or adjust gear, fill magazines, figure out what to do about lunch, or remember that you have no sunscreen (or bug spray, water, or a battery for your optic).

Think through the day in advance and find ways to buy back minutes of precious class time so you can focus on what’s going on, think about what you just saw or learned, and ask questions. In some cases, the time gained back by careful preparation is best applied to rest and hydration, so the next time on the firing line is more focused and effective. Constant scurrying to find ammo, refill magazines, rush off to get lunch, or any non-learning distraction adds to the overall stress and degrades focus.

Prepare to take care of yourself. Unless you routinely spend long days on the range, chances are a multi-day class will lead to some wear and tear. Simple preps, such as applying sunscreen, bringing weather-appropriate contingency clothing, and having liquids and snacks to keep the brain and muscles ahead of the unusual demands, will pay off in your being an active learner when the rest of the line is fading.

Another area that helps is protecting the hands. The combination of several days’ worth of sweat, recoil, and the inevitable edges on rifles and pistols can lead to hot spots or blisters. A high-round-count class will forever change your perspective on aggressive checkering or any edges where the hand lives on the weapon!

I’ve seen more than one shooter finish a high-round-count class with hands so bandaged from severe open blisters that he looks like a boxer wrapping his hands for a fight. Consider masking edges or checkering with electrical or gaffer’s tape for the class. The tape compresses into the diamonds to still provide traction and sticks pretty well but dulls the high points enough to preserve skin.

Many shooters dislike gloves, but rotating shooting or flight gloves into portions of the day can prevent blisters when hot spots start to form. The point is to protect the mind and body so the class can be enjoyed and learning maximized. The shooter wants to be an active student throughout, not a sunburned, dehydrated, and blistered “survivor” just trying to make it to the end.

Profuse and detailed notes will help recall for years after the class and can help shooter continue to learn long after the experience.

GAMETIME

Write down everything. The drills you liked that you want to remember and incorporate into practice (you’ll forget the specifics, to much frustration). The teaching point or fact that struck you. The zeroing data or grouping tendency. Ammo or equipment issues. Your scores and times on drills. Write it all down.

It requires iron discipline to do so, and also to recap the day at the hotel afterward, but weeks, months and years later, you’ll be glad you did. My shooters’ logbooks covering classes and training packages are among my most treasured possessions—to the point that they go in the “hand carry” box in every move.

Be a good student. It can be hard, especially if what you’re being shown challenges your preconceived ideas or practiced techniques. Give everything an honest try. Accept that things that were somewhat familiar may be awkward as you adopt and adapt to new ways.

If the instruction is overwhelming you, the single best thing to do is ask the instructor, “What’s the most important thing for me to fix?” and focus on that. It’s difficult to do more than one conscious thing at a time, and fixing the most broken thing tends to take all available circuitry. Good instructors know this and correct accordingly or do it in sequence so that the stud’s mind can take the corrective actions as steps.

Conversely, if the instructor is not saying much to you and you aren’t sure you’re doing as well as you wanted to, ask, “What is the most important thing for me to improve?” Believe it or not, many students don’t welcome any correction and have paid to shoot rather than learn, so some instructors will hold off if the student is “good enough.” Make it clear that you want the instructor’s perspective.

Genuine conscious mental effort often takes on an unpleasant facial expression and has led to many misunderstandings where the instructor thought the student was unreceptive when in fact the stud was giving the concept a mental workover and just had the frowny-thinking face. If there is a significant age or social barrier between student and instructor, this phenomenon tends to be heightened. Be a good student.

POSTGAME

In every class, you will be exposed to new material. After shaking it out and thinking about if it goes in the “keep” or “discard” pile, consider the technique, drill, recommendation, whatever against four criteria, all of which need to align acceptably: Mission, Anatomy, Equipment, and Skill Level.

This topic probably deserves separate detailed treatment, but suffice it to say that “universal” techniques, like other one-size-fits-all things, often don’t. What works for a dedicated practitioner who trains weekly for a very specific mission on a specific weapons platform may be wholly inappropriate for a basic user with tiny hands, a bad back, a different weapon, and infrequent access to practice.

If the instruction is incompatible with your intended usage, physical makeup, gear, or skill level—don’t sweat it. You may be able to adapt it or simply move on. And it may apply down the road when one or more of those factors change.

Whether a one-time proposition or a yearly endeavor to move up the path of mastery, training is a tremendous investment.

Good luck and good shooting!