Pincus has seen many students cover themselves and/or induce malfunctions while trying to verify that the chamber of their pistol was loaded on a tactical training range. This is an administrative maneuver that would never be appropriate during a dynamic critical incident and shouldn’t be encouraged in a tactical training environment.

Back in the mid-1970s, the United States had a mandatory top speed limit of 55 miles-per-hour (mph). Since that time, we’ve learned a few things about improving highway safety and the safety of our vehicles and, of course, we’ve dramatically improved the efficiency and cleanliness of the internal combustion engine. A lot of things have changed since that time in the world of firearms and tactical training as well.

Progressive training principles and the study of what really happens during lethal critical incidents have dramatically improved the efficiency and capabilities of shooters as well as our gear. Unfortunately, we still see a lot of gun handling that is based on what might have made sense or been a dramatic improvement three decades ago, but are not the most efficient choices today. There is also still a lot of administrative gun handling seen on today’s training ranges. It’s time to take a hard look at some range practices that some people might still consider appropriate, some just accept, some don’t notice, but that many instructors and students are starting to move away from or restrict entirely.

I know that this article will raise the hackles of many shooters, but I also know that more and more often I have other instructors and students who are glad to hear that at the Valhalla Training Center and many other ranges around the world, there are people who are willing to critically examine dogma to develop the best doctrines possible. If you insist on driving 55 mph on an interstate with a 75 mph speed limit, you could be a danger to yourself and others. In today’s tactical training environment, there is no passing lane, so let’s get everyone up to speed.

Table of Contents

“TACTICAL” RELOADS

Years ago, I started forbidding “topping-off” on any range that I was running. The so-called “tactical” reload is just another version of topping off if you’re not in a real or simulated critical incident. The fact is that this and several other bad range habits, many glamorized by competition shooters or preached by instructors who have largely missed or ignored the last 20 years of reality-based training initiatives, should be understood in the context that they are meant for and not repeated constantly on ranges purporting to be conducting tactical training.

Back when dinosaurs roamed the earth, I’ve been told that some instructors on certain ranges made students feel bad if they let their gun run dry. In a world of techniques based on competition or mechanical shooting skills that overemphasize precision marksmanship over speed and efficiency, that might make sense. Teaching shooting as an isolated mechanical skill and not as a defensive skill that may need to be used in a dynamic chaotic environment keeps some techniques from being recognized as inefficient or extremely limited in application.

In the real world that armed professionals and those serious about self-defense are training for, the vast majority of critical incidents that require more rounds than your gun holds will result in a slide lock situation. This is bad. It’s even worse if you’ve been denying yourself the opportunity to recognize slide lock during dynamic training and practice a reload under those conditions as often as possible. If someone else has been denying that opportunity with instruction to the contrary, it’s almost criminal. Because the term “tactical” has already been applied to what is arguably a strategic endeavor (topping off before rejoining the fight), we call this a Critical Incident Reload.

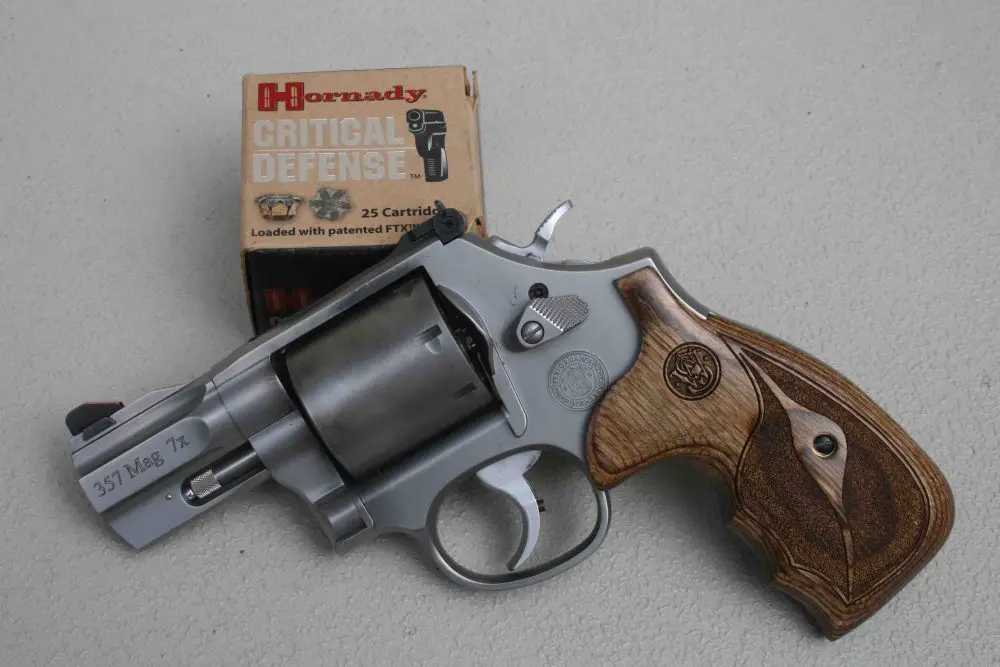

And, of course, progress has brought us to a point where many shooters interested in defensive issues are using firearms with a capacity noticeably greater than seven or eight rounds. These high capacity guns are less likely to need reloading during a typical incident and the magazines that they use are much harder to hold in the ways typically suggested for a textbook “tactical” reload.

I am not saying that students shouldn’t be introduced to the concept of the topping-off reload, but it should not be the student’s primary method of reloading. In fact, I think it should only be used in context during force-on-force or live-fire scenario training. The concept is simple: If you’ve been shooting and there is a lull in the action, you don’t need to move, you don’t need to communicate with someone and you don’t need to do something else. You do need to have fully loaded gun. Eject the partially empty magazine and insert the new one. If you happen to retain the partial mag or pick it up off the ground, don’t put it where you keep your full mags. Proceed.

Three shooters are reholstering, but still have their attention focused downrange. Second shooter from left is reholstering and preparing to walk off the firing line. The practice of relaxing after a string of fire is purely administrative and should not be tolerated on a training range.

PRESS CHECKS

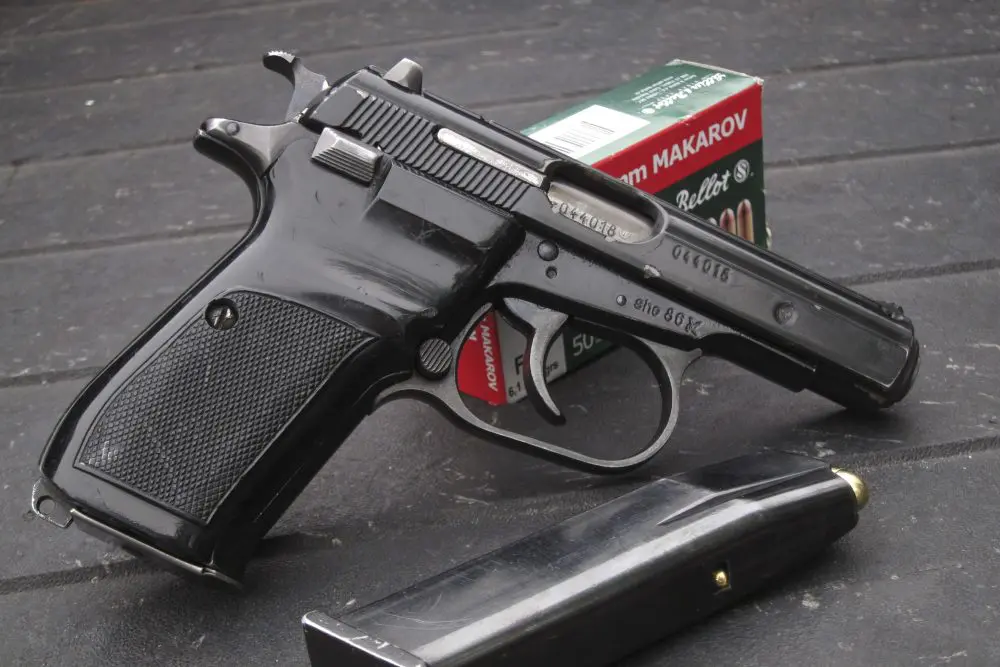

Next on the “what not to do” list: Press Checks. This includes any technique by any name that suggests you take the firearm partially out of battery to confirm the presence of a round in the chamber. Many modern defensive/duty pistols actually have reliable loaded chamber indicators. (XD and the M&P are two examples that jump to mind.) Those should suffice for those of you who do it “just to be sure” before you holster at the next stage of the local Defensive Pistol Shooting Club Match. For the rest of us, think about the most likely reason that the gun will not have a round in the chamber if you have racked the slide fully back and it has gone fully into battery? Most readers of S.W.A.T. Magazine will have come to the quick conclusion that there must not be a properly loaded and working magazine seated properly in the gun. This used to be much more common with typical gun designs of the leaded-fuel era that had flat base plates that recessed into the grip. It is much less likely today.

If you still want to do some type of check, try this: pull on the magazine and see if it is seated after you rack the slide in an administrative environment (more on that later). If it is seated and you later find that no round was in the gun, something is drastically wrong. If this happens more than once, especially if you don’t find the magazine to be the culprit, take the gun to a gunsmith—quickly.

Furthermore, using the same logic explained above for topping off, why cheat yourself out of the learning opportunity on a square range of finding out that you aren’t seating the magazine properly during your reloads (with the added bonus of a non-staged malfunction drill)?

I used the word “administrative” a few lines ago—this “technique” is only practiced in an administrative setting—that is your first clue that it has no place on a tactical training range. No one would suggest doing a press check after a slide lock reload in the midst of a string of fire, let alone in a real or simulated critical incident.

Before the emails start: No, this is not just a “Rob wants to complain about something” issue. I have seen many, many more students on ranges induce malfunctions and/or cover themselves with the muzzle while performing press checks than I have ever seen finding an empty chamber. This practice is the equivalent of running to your basement and looking for puddles after you flush your toilet. It is at best a waste of time, and at worst it leads to a negligent discharge with injuries. If your gun is working, trust it to work until it fails—that is part of what your training time should be about.

Lastly, (again to stave off emails), make sure that your pistol really is loaded before going on duty, on patrol, or out in public with the intent of using it for self-defense or the defense of others. Competition Shooters: you deserve to lose the stage if you didn’t load your gun properly.

“I’M OUT”

The third thing that I am going to address is the use of the phrase “I’m out” with a slide-locked gun that still has an empty magazine in it in your hand. This is often accompanied by a somewhat vacant look over the right or left shoulder at the instructor running the line. The advanced version of this maneuver is done by ejecting the empty magazine into the weak hand prior to using the phrase. Now, I will assume that no one has ever actually taught anyone else to do this, but it does seem to happen a lot—and it is a close cousin of the automatic “unload & show clear” business from competition fields. Some competitors actually look like they think the clock is still running until they pop that mag and lock the gun open to show the safety officer how fast they can make their gun less dangerous. Stop. Please.

Any time you are on a tactical training range and the pistol locks open, follow your procedure for a critical incident reload. This should be something like pulling the weak hand off the gun, ejecting the empty mag as the gun comes back to the ready position, reaching for a fresh mag with the weak hand, etc. If you find that there is no magazine, simply come back up to the pistol, pretend to insert a magazine and rack the slide.

For those of you who carry an extra magazine, how much more likely is it that you’re going to have slide lock and an extra magazine than that you would have no extra mags left and an instructor standing over your shoulder? A huge part of tactical weapons handling efficiency is consistency in practicing your mechanical skills—get as much practice as you can.

For those of you who don’t carry extra mags, picture how intimidating a person with a locked open gun saying “I’m out” is. At least standing in the ready position or moving to cover with a gun that is in battery is a plausible threat that might prevent your enemy from taking pot shots from behind cover or get him to give up altogether.

SPEED HOLSTERING

The last topic I’ll address in this article is holstering while walking off the line. Again: Please Stop. If the gun is loaded, this is dangerous. If the gun isn’t loaded, it is inconsistent bad practice. The procedure when you are working from the holster is this: Recognize a threat, draw and fire, come back to the ready, assess the environment, re-holster, then relax. Your body posture shouldn’t change from string of fire until after you have re-holstered the weapon. Until that time, you should still consider yourself in a critical incident and be as ready for dealing with a threat as possible. The practice of relaxing after a string of fire is purely administrative and should not be tolerated on a training range.

Armies used to stand in tightly knit groups and meet on open fields of battle exchanging volleys of fire. Police officers used to catch the ejected brass from their revolvers on the range during training and put it in their pockets to make clean-up easier at the end of the day.

Everything we do on a tactical training range should be critically examined and subject to improvement, revision or eradication. If you do any of the things I discussed in this article, especially if you teach or allow some of them, I think you owe it to yourself and your students to re-examine the practicality of those techniques and re-dedicate yourself to maximizing efficiency and reality in your tactical weapons handling. They may just be bad habits, but some bad habits can get you killed.

[Rob Pincus is the Director of Operations at the world-renowned Valhalla Training Center, www.valhallatraining.com.]