The .38 Special enjoys a well-deserved reputation as an accurate and pleasant-shooting cartridge. It’s just about perfect for building and maintaining skill without punishing your extremities or your guns.

Reloading .38s is an economically sound endeavor—it has permitted me to keep shooting steadily upon retirement even after my stash of issued ammo dried up. It also opened my eyes to the efficiency and usefulness of this old round.

Shooting PPC gave me access to piles of once-fired brass, thanks mostly to some generous federales. Using once-fired stuff cuts down on trimming brass, especially when the original load was a target wadcutter. I trim brass when necessary, but avoid it whenever possible because it’s a tedious chore with my basic equipment.

.38 Special has always been a good candidate for ballistic improvement via homebrewing. Even with today’s advanced ammunition, the cartridge can still be upgraded with careful handloading.

Table of Contents

MY RELOADING PROCEDURES

My Hornady tumbler can handle 100 to 150 .38 cases at a time. Four to six hours usually polishes them sufficiently; the tumbler media tapped from cases one at a time as they’re removed. Some folks de-prime cases prior to tumbling, but this adds a step, as you have to poke media out of flashholes on most cases tumbled this way.

Once clean, cases are full-length resized and de-primed. I use an RCBS single-stage Rock Chucker for all my reloading. My dies are an old set of Lee Carbide inherited from my dad. They aren’t fancy, but they work like a charm.

Primer pockets are inspected and cleaned as needed. Again, scraping with a tool can usually be avoided on once-fired brass. Cases are then belled just enough to reluctantly accept the bullet being used. I use an RCBS hand-priming tool to seat new primers. Hand-priming tools allow you to feel the primer seating, and you can seat them just below flush without crushing them. Running a fingertip over the head of each primed case will insure proper primer height.

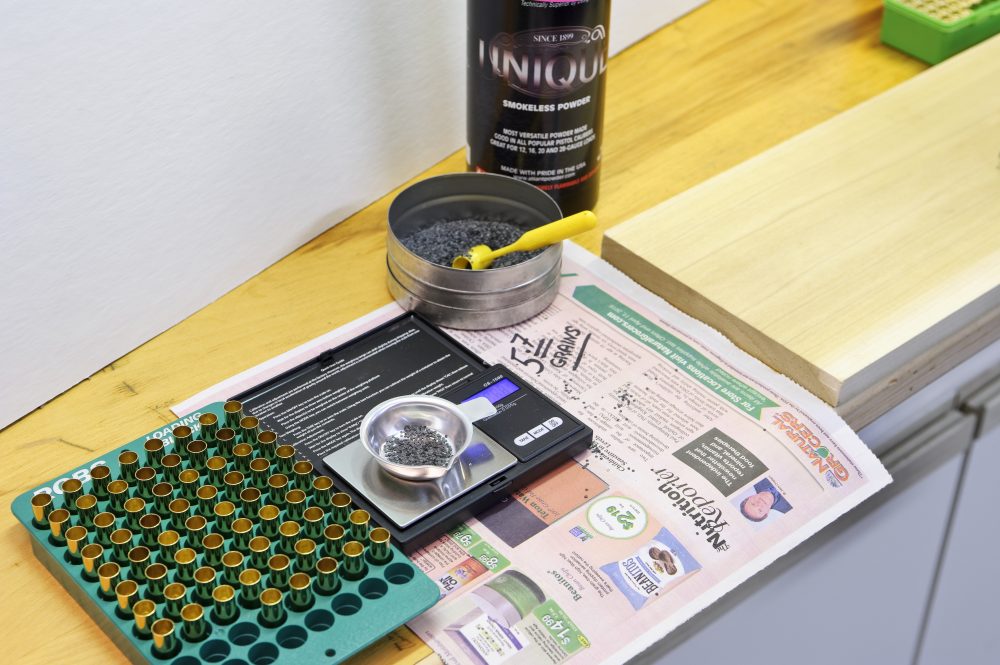

I put powder in cases at my kitchen table with an inexpensive Hornady electronic scale. I own scales that cost more, but the little Hornady is easy to work with and has proven trustworthy. I’ve found that minimizing all possible scale interference is worth the trouble. Turn off nearby fluorescent lights and the heater/cooler. The dishwasher and clothes washer and dryer should also be left dormant. If it’s noticeably windy outside, wait for better conditions. The Hornady scale holds zero and fluctuates very little when these steps are taken. If it varies more than a tenth of a grain, turning it off and back on until it recalibrates usually settles it down.

Bring only one can of powder to the table to avoid confusion. Set the scale on a newspaper with the intended powder charge written on the newspaper with a Sharpie. This gives instant reference in the event of daydreaming or leaving the table to check a kid’s homework.

I weigh every powder charge—the consistency of performance provided is worth it. This practice virtually guarantees the proper amount of powder going into each case and eliminates squib loads. I’ve seen some good powder measures vary the charge thrown more than I’m comfortable with.

Alliant Power Pistol was designed for high-velocity loads in semi-auto cartridges like .40 S&W. It provides superior performance in the old .38 Special too.

The only exception to this rule is when IMR’s Trail Boss is the propellant selected. A pre-measured homemade scoop can be used to greatly speed up filling cases. Trail Boss is the go-to powder when I’m building large quantities of practice ammo with cast bullets.

When all cases are full, shining a flashlight on the loading tray confirms they all have powder in quantities that look equal. On my pilgrimage back to the garage, the loading tray is the only thing I’m carrying. Dropping a whole tray of laboriously loaded cases on the kitchen floor guarantees spousal irritation and generally fouls your good humor.

Once the tray is safely benched, the bullet seating/crimping die goes in the press. It takes more time, but I have much better results when bullets are seated and crimped in two separate steps.

Secure the die a few full turns from where the crimping shoulder will contact the case with the seater plug backed all the way out. Insert a bullet into a charged case and run the ram up all the way. Screw the seater plug down until it contacts the top of the bullet.

Lower the ram and screw the seater plug in a few turns. Repeat until the top of the bullet’s crimping groove is barely visible. If you’re seating a jacketed bullet, the bullet’s cannelure should end up about 2/3 covered by the case mouth. Lock the seater plug down and fill loaded cases with projectiles.

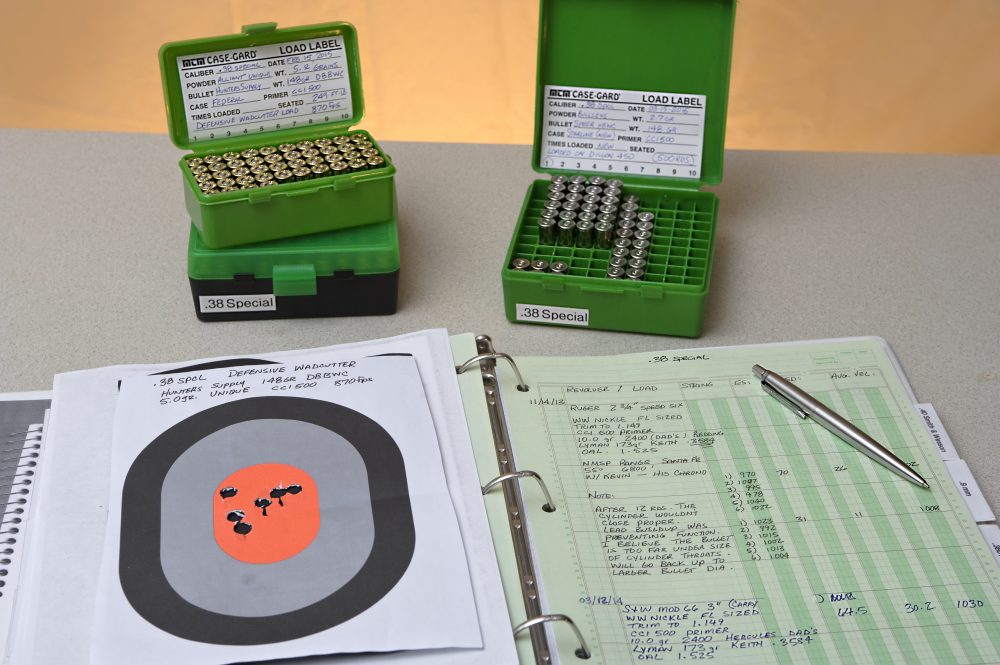

Handloading allows you to wring maximum performance and accuracy out of the .38 Special. Loads can be custom built for the intended mission—often with better results than factory ammunition. Like snipers, dedicated handloaders tend to keep data books. Accumulated information is a great resource.

This is the point where it pays to use once-fired brass of the same headstamp and origin. If you’re using mixed brass, trimming will help achieve a proper crimp by starting with brass of equal length. Regardless of your methodology, crimping will be more uniform and velocities more consistent (at least in theory) if your cases are the same length.

Back the seater plug all the way out again and raise the ram to bring the cartridge fully into the die. Loosen the die and screw it down until the crimping shoulder contacts the rim of the case. Pull the ram to remove the case from the die and screw the die in about a quarter turn. Raise the case into the die and check crimp. Repeat this process until the desired crimp is achieved. Seat the crimped case back in the die fully, tighten the locking ring, and crimp the rest of your loaded cases.

After crimping, wipe the loaded rounds off with a clean rag to remove brass, bullet shavings, and excess bullet lube. Clean ammunition is easier to final inspect.

Load the rounds into the cylinder of the revolver you’re using to insure proper chambering. Close the loaded cylinder, carefully ease the hammer back partway and manually rotate the cylinder 360 degrees to make sure primers are flush with no drag. Loaded rounds should literally fall out of the charge holes when inverted if the revolver is clean.

Power Pistol will launch a 110-grain JHP like Hornady XTP at very respectable velocities in the .38. In the right circumstances, these handloaded cartridges would make a decent defense load.

OPTIONS WITH .38 SPECIAL

The .38 Special thrives on lead bullets; I use them for almost everything I do with the cartridge. For practice ammunition, Cowboy action bullets can be had in weights from 90 to 160 grains. Trail Boss powder in appropriate charges with these bullets makes great practice ammunition.

I use Missouri Bullet’s 140-grain TCFP on a max charge of Trail Boss. This yields 800-ish fps in most of my guns. The load is accurate and mild mannered with no barrel leading issues. These rounds are built for quantity—mixed brass and cases that have been loaded several times deliver acceptable results.

Wadcutters are a good bullet to empower a short-barreled J-frame. They were designed for punching paper with low recoil, putting full-value holes into really small groups. They’re also a decent choice for a defensive load in the little guns, as no expansion is required to cut a .358 hole in tissue (think hole punch instead of ice pick).

There are many different styles of wadcutters out there. Some have crimp grooves that expose a portion of the bullet. Others are designed to be seated flush with the case mouth. Data should not be considered interchangeable between the two. Use published data on the specific bullet that you’re using, and start with minimum powder charges and work up.

Expensive high-tech tooling is not required to build quality ammunition. Proven old tools like the RCBS Rock Chucker press and Lee carbide dies produce exceptional handloads.

COMPARATIVE VELOCITIES

Factory offerings run sedately through my J-frame, averaging 650 to 675 feet-per-second (fps) regardless of manufacturer. With Alliant Unique, 148-grain wadcutters can be driven over 900 fps from short barrels at standard pressure. (The same load clocks 1,051 fps from a four-inch gun but shows some bore leading at that velocity.)

The Powder I have found most compatible with full-power cast bullet loads is Alliant Power Pistol. It’s billed as a semi-auto powder, but it shines in the .38 Special.

You can argue that a 9mm is faster than the .38, and I’d agree with you—on the lighter end of the bullet spectrum. You can certainly best a sanely loaded .38 with the 9mm using 110- and 125-grain bullets, albeit at substantially higher pressures.

Cast bullets are well suited to the .38 Special. Casting bullets allows you to dictate the hardness of the alloy and size bullets to your specific gun. Mold is RCBS 38-150-KT, which produces an excellent all-purpose bullet. Good cast bullets are available commercially if you don’t make your own. Cast Performance 160-grain heat-treated WFN PB is one of author’s favorites. Missouri Bullet Co. 140-grain TCFP is a great high-volume practice bullet used at low to medium velocity.

Because of the 9mm’s limited case volume, it cannot get there with longer, heavier bullets. The Federal 9mm 147-grain TMJ averages 923 fps from my 4¼-inch S&W M&P9. It can be pushed faster, but much past 1,000 fps will get you into +P+ territory.

The .38 Special can drive a 173-grain bullet at that speed and just be nudging into +P pressures. Using a Lyman 358429 semiwadcutter (SWC) with 5.7 grains of Power Pistol averages 973 fps from a four-inch barrel. That’s a very efficient loading of a proven bullet. It’s also accurate at longer ranges and penetrates straight and deep.

The 38-150-KT is RCBS’ version of a shorter, lighter 358429, otherwise staying pretty true to the Keith design. Cast with 50/50 wheel weights and linotype and sized to .3594, it weighs 150.1 grains after lube is applied.

Six grains of Power Pistol yields 1,048 fps. This bullet, sized to the chamber throats of my Model 10, has been exceptionally accurate. It hits to the fixed sight’s point of aim at 25 yards.

Simple electronic scales like this one from Hornady work fine to accurately measure powder charges for handgun loads. Author recommends writing chosen powder charge near the scale for instant reference.

LOOKING TO BUY?

If you don’t cast your own bullets, you can buy some really good ones. Cast Performance’s 160-grain Wide Flat Nose (WFN) is a solid example. I measure brass for this bullet, only using cases 1.143 inches or shorter to ensure chambering in .38 charge holes. This bullet is good enough that I will actually trim brass (ugh!) to use it. You can get 961 fps out of 5.7 grains of Power Pistol.

Lots of inexpensive 158-grain SWCs out there will work well—just avoid swaged lead and really soft alloys if you plan on pushing them hard. The flat meplats (frontal area) of SWCs and WFNs are vastly superior to round-nosed projectiles for transferring energy. The three loads quoted are +P loads but show no pressure signs and don’t lead the bores of my revolvers.

A maximum +P charge of Power Pistol propels a 110-grain Hornady XTP at 1,163 fps from a four-inch gun. A hot 9mm will outrun it, but it’s a respectable load if you favor light bullets. Consider it a “social” load, like the defensive wadcutter mentioned earlier.

Many styles of wadcutters are available, swaged soft or cast to varying hardness. Select hardness (BHN) suitable for the intended velocity and use data for the specific bullet you choose. Speer WC (left) loaded inside case mouth. Harder ACME bullet (right) has a crimp groove to allow seating the bullet farther out of the case. Data should not be considered interchangeable.

HANDLOADS’ BAD RAP

It’s become accepted advice that only factory ammo should be carried for defensive purposes because “handloads are unreliable and an unscrupulous attorney’s dream.”

There is no reason why carefully assembled handloads cannot equal (or surpass) factory ammunition reliability. I can’t find a case where an otherwise “good” shooting was tainted by the use of handloads. Current and former prosecutors I have spoken with likewise have no knowledge of handloads reflecting negatively on the user.

Handloading lets you custom tailor ammunition to your particular handgun. You get to choose projectiles specifically suited to the application, and you have the final say in ballistics.

Experimenting with components and powders can dramatically improve accuracy. This makes for a rewarding pursuit and actually provides pride of ownership in what you are sending downrange. Handloading makes a pretty good case for the old .38 Special.

[Caveat: Since S.W.A.T. has no control over reloading practices or equipment used, this article should be used for information purposes only, and S.W.A.T. assumes no liability for accidents or injuries that may occur by using loads in this article.]

SOURCES

ALLIANT POWDER

(800) 379-1732

www.alliantpowder.com

CAST PERFORMANCE

(307) 857-2940

www.castperformance.com

MISSOURI BULLET COMPANY

(816) 597-3204

www.missouribullet.com