I have studied ballistics for a while, my middle-school science fair project on bullet weight and trajectory during the Reagan Administration as an example. But until a few months ago I had never reloaded a single cartridge.

I’ve been on the taxpayer subsidized skills development and ammo program for a long time, and it was just simpler to buy any personal ammo in bulk than to reload. I recently decided to take on the challenge and learn the “assembly” side of the ammo. I figured that some readers who are similarly dithering on whether to begin reloading or not might be interested in hearing how my experiment went.

Table of Contents

SETTING UP

Right off I defined my objectives to help guide my effort and measure progress. After kicking it around at length, I determined I had three goals:

- Gain flexibility in the event of the all-too-frequent retail shortage of loaded ammunition. Being able to load my own on demand would offer uninterrupted sustainment. This would require reliability and accuracy in line with generic loads.

- Gain the ability to tailor loads to my requirements, whether accuracy or a desired level of velocity and/or recoil.

- Cut the cost per round of more expensive calibers.

Soon I had a Hornady Lock-N-Load AP progressive press in hand and all the necessary accessories to make ammo. Assembling and mounting the press was a simple chore that should challenge no one with the mental acuity to be handling firearms.

The press came with a helpful DVD that patiently and thoroughly walked the reloader-to-be through the whole process. Full disclosure requires I admit that the dies themselves, while pretty straightforward, had me a little intimidated. I double-checked my work setting them up with a couple of YouTube videos that helped get me over the hump. The very first setting up of the dies took me about an hour as I carefully read directions and triple checked everything.

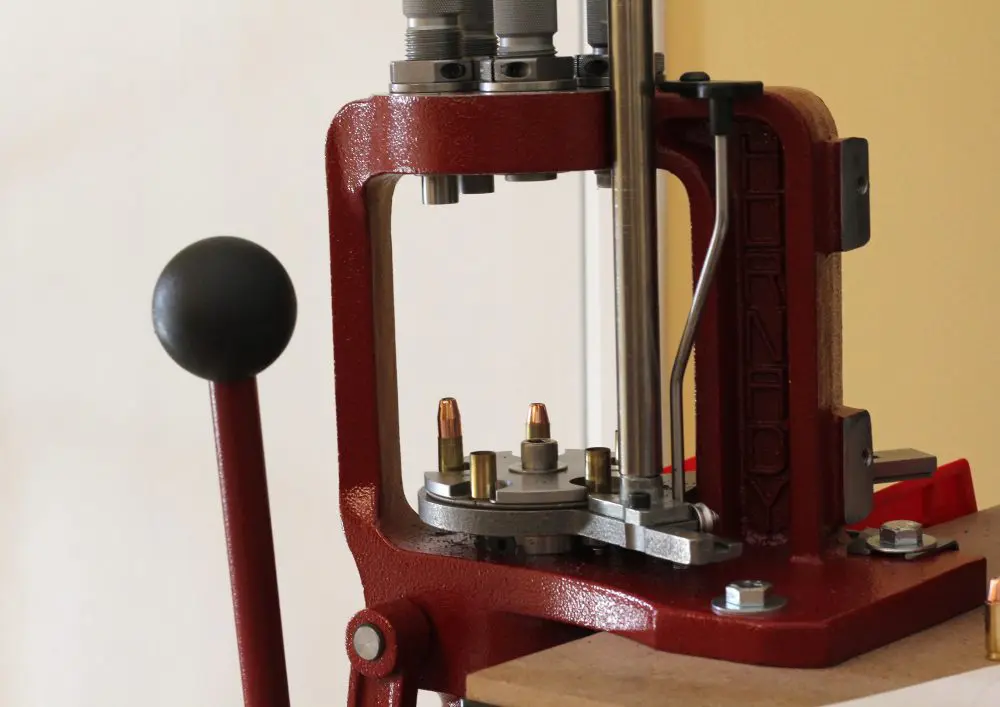

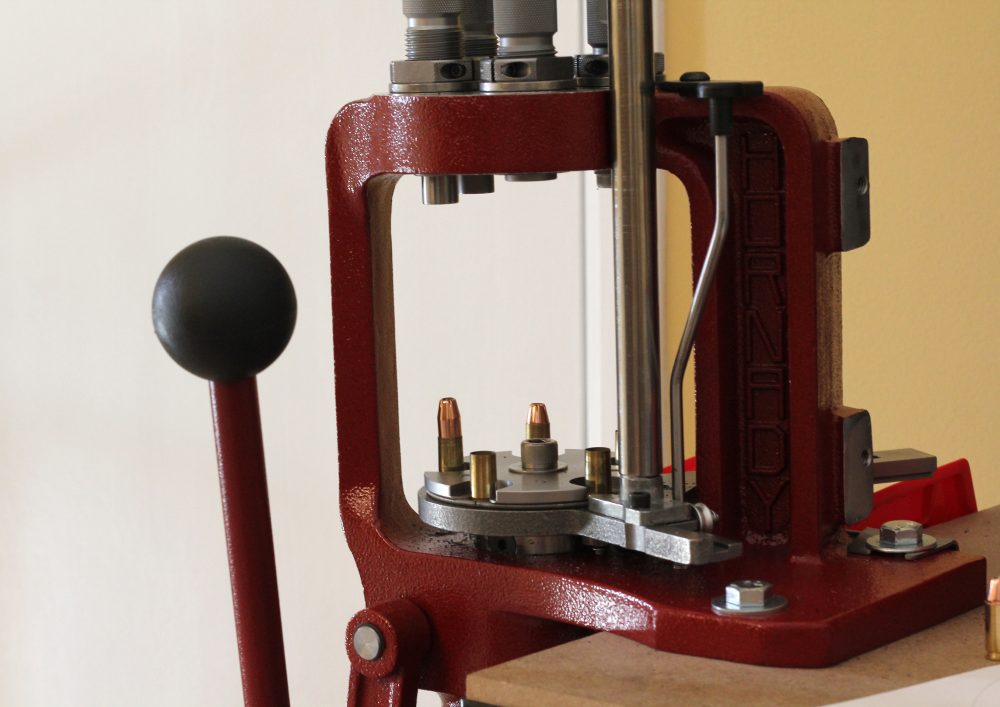

Now every stroke of the handle would in turn resize and knock out the spent primer in the first die, seat a new primer, slightly bell the case mouth in the second die, activate the powder drop in the next station, and both seat and crimp in the bullet in the third die. The press then kicked out the loaded round into a hopper.

I had been apprehensive about the powder drop and bullet seating stations, but both were very simple to adjust. Need more powder? Back out the threads on the powder measure an eighth or quarter turn and check the powder weight. Repeat as necessary. Change a light bulb simple. Similarly on the seating die, slowly “walk in” the seating depth by tightening the die a little at a time and rechecking until the bullet is at the desired depth.

How hard can it be? Progressive press easily puts the four pieces together.

My initial learning curve was about 150 rounds. To begin with, I slipped a single piece of brass into the shellplate and cycled it through each station individually to gain a better understanding and “feel” for the cycle of operations. Doing this for the first 50 or so rounds was helpful to get the hang of how the press worked. I then slowly started increasing the number of cases in the press each time.

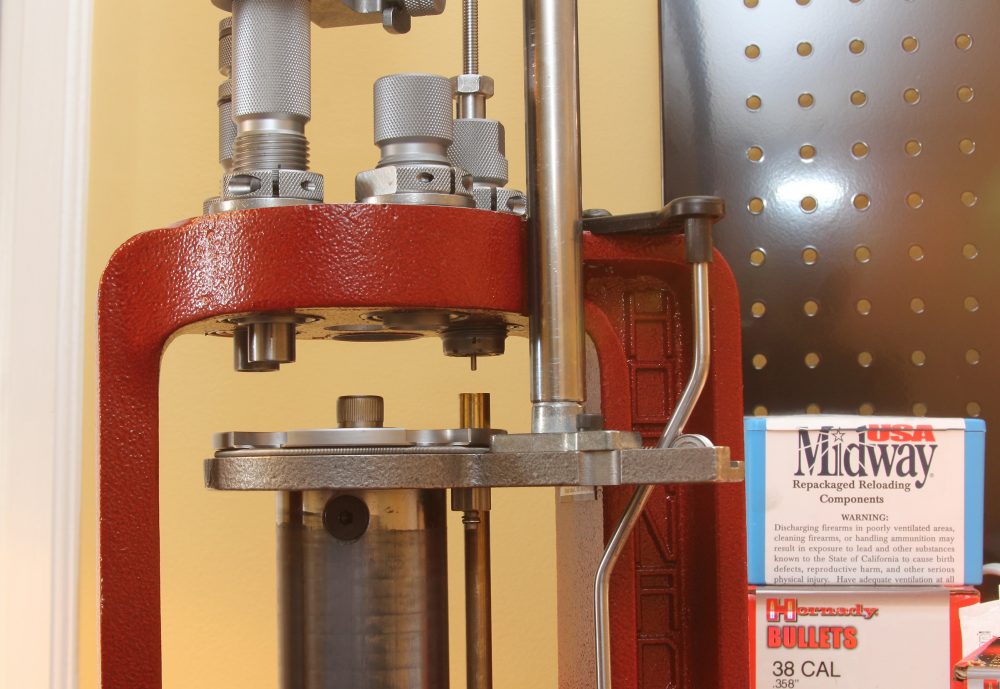

My first 100 rounds were challenging. Because I had not quite set the resizing/depriming die correctly, operation was not smooth and required constant readjustment. This was borderline anger management therapy and entirely operator error. Once I set the depth of the die correctly (as indicated in the directions … “Oh, that’s what they meant!”) and tightened down the locking rings and decapping rod, the clouds rolled back, the sun shone onto the press, and the angels’ chorus could be heard softly in the distance.

Author was surprised at how much satisfaction he felt in his “custom built” ammo./em>

In those first few boxes of ammo, I made a number of mistakes, all preventable and part of the learning process. Rounds without primers, crushed case mouths, etc. My failure rate would have gotten me fired from any respectable business.

But by the time I was at 250 rounds, I had a solid sense of the process and my errors decreased to the occasional hiccup as my production speed increased. By my seventh loading session, I could feel each stage simultaneously through the press and had smoothed out the little movements: this hand grabs empty case and slips it into shellplate, that hand grabs bullet and places it while standing precisely there, gives best reach to the components and leverage to smoothly cycle the handle.

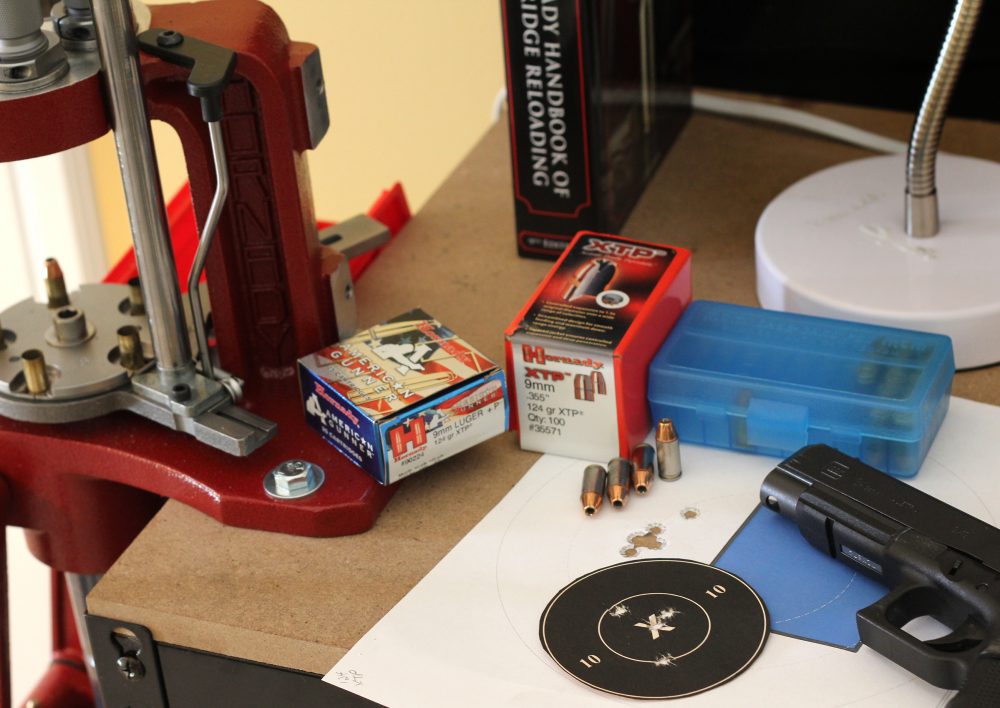

Several handloads excelled in the Glock 34. Author was nearly able to duplicate American Gunner 124-gr. +P with an XTP load and outperform generic ball with a 115-gr. FMJ.

OFF TO THE RACES

By 500 rounds I was very confident in the whole process and was able to move some parts of the operation away from conscious effort. I was cranking out a box of 50 rounds with no errors in about 15 minutes, or 200 rounds an hour.

I was swapping back and forth between 9mm and .38 Special, and at this point—with the dies all well adjusted—the outstanding Hornady Lock-N-Load bushing system let me swap between calibers in four minutes or less. The dies slip into the press with a simple quarter turn to lock, much like an AR bolt locking into the barrel extension, requiring only the correct shellplate to be bolted in and the length of the powder drop adjusted for the caliber.

As I crossed 1,000 rounds, I had swapped back and forth between the calibers regularly and easily and set each die for a variety of bullets and charge weights. I next timed myself at about 1,200 rounds and was putting a box of 50 together in right at 10 minutes. Of course, accessories exist to speed production even further, but this rate exceeded my initial expectations and is working out well for me so far.

Ruger GP100 Match Champion was a tack driver with a variety of loads. Handloaded XTPs came very close to factory American Gunner’s accuracy.

GOING HOT

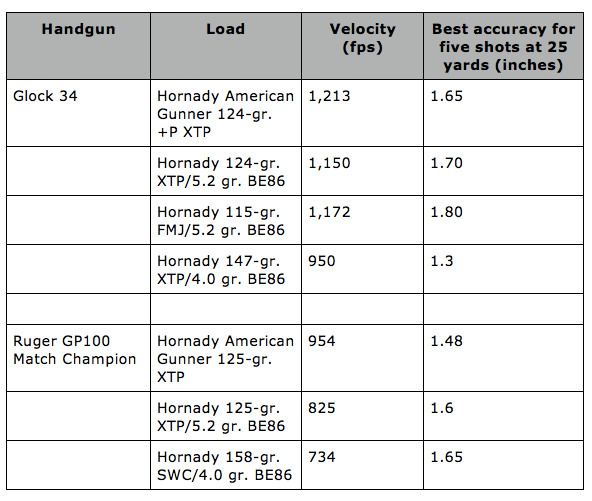

I tested the loads primarily in a Glock 34 and a Ruger GP 100 Match Champion that I had on hand. As a baseline, I shot each with Hornady’s American Gunner loads. The American Gunner line uses the XTP hollow point, which has a well-deserved reputation for accuracy. That proved out here as well. The Glock put the 124-grain 9mm +Ps into 1.65 inches at 25 yards. The .38 Special American Gunner XTPs did 1.48 inches at 25 yards from the new Ruger.

My first box of 9mm reloads were 124-grain XTPs that stepped out at 1,150 feet-per-second (fps) from 5.2 grains of Alliant’s BE86 powder with Winchester Primers. A composite of three groups had the best nine shots in 1.4 inches at 25 yards. Five-shot inclusive groups hovered around 1.75 inches. It definitely inspired confidence to have the first load attempted do so well, since many pistols will never see a 1.75-inch group with any load, let alone a newbie’s homebrew.

The Match Champion grouped up to its name, with handloads of 125-grain XTPs at 825 fps doing about 1.6 inches at 25 yards. One 20-yard group had four shots in a ragged .65-inch hole. Another score for beginner’s luck! This was a pleasant-shooting load that happened to shoot directly to point of aim in my Airweight J frame and produced one of the best standing 25-yard strings I’ve ever laid down with the pocket gun.

Each cycle of the handle simultaneously deals with each step of assembly and advances the shellplate of the Lock-N-Load AP press. With a little practice, production rate was a box of 50 loaded cartridges every 10 minutes.

The Ruger is a consistently accurate revolver, grouping 1.8 inches with Winchester FMJ loads and 1.75 with Winchester 148-grain wadcutters at 25 yards. My attempts at wadcutters are still ongoing, with no standout results yet, just acceptable practice accuracy of 2.5 inches plus. Challenge accepted. My try at a standard-pressure 158-grain semiwadcutter has been more successful, with the Ruger throwing those out at 735 fps into as little as 1.65 inches at 25 yards, with average groups about 2.2 inches.

In 9mm I put together a load to duplicate generic bulk ammo with 115-grain ball at 1,172 fps. It is averaging about 2.5 inches at 25 yards, with best groups down to 1.8 inches. That is right on par with what Magtech, Winchester USA, or Federal does in that Glock 34. The handloaded 115s enjoy the distinction of being the load used for my current personal record on the 10-Shot Assault drill, so I am pretty satisfied.

Next, wanting to try a heavy bullet load in the 9mm, I tried the 147-grain XTP loaded to 950 fps, which is really soft shooting for the performance it brings. It is boringly consistent at two inches or less, with the best group a remarkable 1.3 inches at 25 yards.

As I have gotten more proficient and consistent in working the Hornady press, the loads are reflecting that. My current loads are each showing an extreme spread in velocity of 20-something feet per second, showing a level of consistency on par with most quality factory loads. Feeding and ejection have been 100% in 9mm.

Author battled resizing die for the first 100 rounds until getting it set correctly. Lesson learned: if it’s not working smoothly, it isn’t set correctly.

PENNIES

Many are attracted to reloading for cost savings. A wise friend shared that you don’t save money, you just shoot more. I can see the point, but it does feel good to calculate the price per round and compare. Figuring the set-up cost as a sunk cost, I estimate my savings in .38 Special to be as much as 27 cents per round. Even shooting the laser accurate XTPs, cost per shot is 10 to 15 cents less than generic .38 factory loads.

Supply, demand, and economies of scale make 9mm less dramatic in the savings department. I estimate I am saving 3 to 5 cents a round in ball ammo, but can handload the target-quality hollow points for nearly identical cost to buying bulk ammo.

The savings is greatest in the less-common calibers. I estimate that the break-even point from buying the dies, shellplates, and bullets is as little as 150 rounds for some larger calibers as compared to buying factory.

Standing 25-yard group fired with 125-grain XTP handload and S&W 642. Shooter can build top-quality practice loads that duplicate carry ammo for much less than cost of generic practice ammo.

WAITING?

My three objectives were each handily met. I am now able to choose between making or buying ammo. I wasn’t looking for a hobby, but now I feel the pull of tinkering with a load, chasing better performance for a certain application or a specific gun.

What I wasn’t expecting was the satisfaction I feel when looking at a cartridge I’ve made. Even more so when they pile into tiny groups or lead to personal bests. Personal pride is a funny thing, popping up in unexpected places.

I work with some of the nation’s finest, and it regularly humors me how men can shrug off noteworthy accomplishments and feats but be tickled over the smallest thing. Shooters who are on the fence about reloading may give it a hard look—you too can be grinning down at a handloaded round as it is ejected from the press. I wish I had taken the plunge at least 15 years ago.

Next challenge: Rifle ammo.

Ethan Johns is a military professional with worldwide experience in specialized units. He has taught and been responsible for numerous advanced skills and weapons courses within multiple organizations.

SOURCE:

HORNADY MFG. CO.

(800) 338-3220

www.hornady.com