Today’s use by U.S. armed forces of highly accurate semi-auto sniping rifles such as the M110 SASS or the SR-25/Mk 11 Mod 0 is considered a tactical advantage. These rifles are so accurate that shots may be placed with precision that rivals bolt-action 7.62x51mm sniping rifles.

During World War II, the general issue of the semiautomatic M1 rifle (Garand) presented problems for development of a sniping rifle based on this system. One major problem was that positioning a scope above the bore would preclude using the Garand’s eight-round clips. For much of WWII, the solution was to use bolt-action sniping rifles based on the M1903 Springfield, including the 03A4.

Troops undergoing weapons familiarization training see M1D demonstrated. Photo: National Archives and Records Administration

But on 27 July 1944, a sniping version of the M1 designated M1C was adopted. To allow use of the eight-round clips, a mount designed by Griffin & Howe, which positioned the scope on the left of the receiver, was employed. The scope adopted was the Lyman Alaskan in two versions: M81 with crosshair reticle and M82 with tapered post reticle. Frankford Arsenal studies determined that the tapered post proved more effective with most shooters.

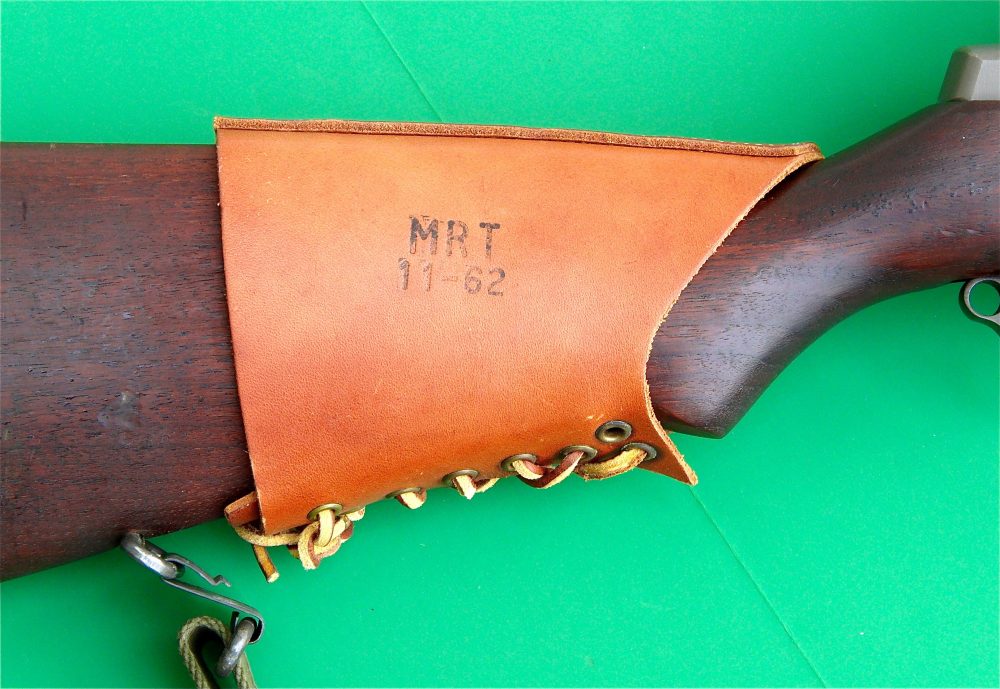

These rifles were equipped with the M2 conical flash suppressor, which attached in the same manner as the M7 grenade launcher. Many marksmen did not use this flash hider, as they found the mounting method adversely affected accuracy. To properly position the shooter’s eye for the offset scope, a T4 leather cheek pad was fitted.

By the end of WWII, 7,971 M1C sniper’s rifles had been produced, though they saw little use before the end of the war. The M1C was used during the Korean War along with the M1903A4.

Close-up of later T37 pronged flash suppressor used on M1D in Vietnam

Another sniping version of the M1 was the M1D, which used a different mount designed by John Garand. The mount fit directly onto a Garand barrel rather than on the rifle’s receiver.

The scope was the M84 2.2X, which was produced by Libby-Owens-Ford and Leupold & Stevens. This scope had originally been built for the Springfield M1903A4 sniping rifle. The military bid specs reportedly called for a 27-foot field of view at 100 yards, which limited the magnification.

M1D rifles were also fitted with the M2 flash suppressor and T4 cheek pad. The M1D was adopted in September 1944 as substitute standard, but none were produced during WWII.

M1D’s offset M84 scope

In December 1951, 14,325 rifles were requisitioned for conversion to M1Ds. Springfield Armory produced enough of the special M1D barrels from 1951 to 1953 to meet the demand for these conversions plus possible future conversions. The barrels were not special match barrels, but standard Garand barrels.

Many M1Ds were used in Vietnam, though often with the T37 pronged flash suppressor rather than the conical one. Many of these M1Ds saw service with Special Forces and Vietnamese troops operating with SF. The USMC also used M1D rifles in Vietnam, in at least some cases accurized by Marine armorers. Normally, match ammo was not available to troops using the M1D, so they used the heavier AP loads, which stabilized better and hence were more accurate.

Right side view of cheek pad designed to position shooter’s eye for use of offset scope on M1D

The side-mounted scope also creates a parallax problem. If the scope is zeroed at 100 yards, it will shoot quite a bit to the right at 200 yards and even more at 300 yards. Zeroing at 200 yards is another option. The side-mounted scope does allow the iron sights to be used. Normally if they are zeroed at 25 yards, then elevation is raised one click, the rifle can be used relatively well between 0 and 400 yards. If the M84 scope is zeroed at 200 yards, shooting groups should give some idea of windage adjustments at various ranges.

While working on a book about the M1 Garand a couple of years ago, I shot an M1D for the first time. I was most interested in evaluating its ergonomics and seeing how difficult it was to use the offset scope. I had some non-corrosive .30-06 ammo I had gotten from the CMP, already in eight-round clips, and used it for the testing. As I remember, it was standard M2 150-grain ball from the early 1950s.

I have to admit that I am spoiled by modern scopes with options such as Leupold’s BDC (Bullet Drop Compensation) dials that let me zero at 100 and just turn the elevation dial to the distance at which I want to shoot (e.g., “3” for 300 yards).

Vietnam-era M1D

I zeroed the M84 scope at 200 yards—with some effort, I might add. I then fired multiple three- and five-shot groups. My best three-shot group at 200 yards fired from a rest was 5.75 inches. Most were closer to seven inches, plus or minus—more plus. I did manage one five-shot group that was seven inches. I was not using match or even AP ammo. I also tried shooting using the iron sights and actually did almost as well.

As I said, I was mostly shooting the M1D so I’d have some idea what the infantryman in Korea or Vietnam would have experienced when using it. First, the leather cheek pad is definitely needed to get a cheek weld that lets the shooter use the offset scope. The self-loading action would have been a boon, as it allowed a quick follow-up shot to adjust point of aim, especially if a spotter with more magnification were assisting.

On the other hand, recoil with the Garand is noticeable enough that it took me an instant to reacquire my target after each shot, especially with the rather fine crosshairs of the M84. I know there were troops who did good work with the M1D in Korea and Vietnam. I would have to grant that they were better shooters than I am.

View from rear of offset scope, which allowed M1D to still be loaded with eight-round clips

My own view is that the M1D is, being generous, a DMR (Designated Marksman Rifle). It is not a true precision sniping rifle capable of long-range kills. It would have been most effective when used from a concealed position at relatively short ranges, say under 300 yards.

Still, it is a very interesting U.S. military collectible firearm. Any Garand or U.S. sniping rifle collection needs one. And if you get a chance to shoot one, definitely do so.

Leroy Thompson has trained hostage rescue, close protection, counterinsurgency, and anti-terrorist units in various parts of the world. Prior to Operation Desert Shield, he trained U.S. Army protective teams and hostage rescue units. He is the author of over 50 books on weapons and tactics and somewhere between 2,500 and 3,000 magazine articles.