Motionless Operators Ventilate Easily (M.O.V.E.) is one of the phrases we use during our firearms training courses. It comes from our mantra that, if you are not behind cover or concealment when a gunfight starts, you should be moving toward it, or at least, moving off the line of attack as quickly as you possibly can. Firearms training schools spend the majority of their time concentrating on teaching their students to induce trauma and not relieve it (as they should be), but unfortunately many students walk away with the impression that dealing with gunshot wounds isn’t part of the gunman’s responsibilities. It is.

Students in medical class use car for concealment and begin gunshot wound care.

I often ask my students during classes, “Is it more important to shoot the bad guy or for you not to be shot?” A few overeager students blurt out, “Shoot the bad guy.” As they are finishing their answer, their brain fully deciphers the question and they look embarrassed. It is indeed more important not to be shot than it is to shoot the bad guy. But the reality of gun fighting is that sometimes we don’t move fast enough or our partners don’t move fast enough—and a good guy ends up getting wounded.

The current thinking is that you first apply self-aid to these injuries. The days of shouting “MEDIC!” and somebody running up to you are a thing of the past. Modern medics are riflemen first and medics second. The next level of care is “buddy aid,” where after the fight is quelled somewhat, your teammate assists you. The third level of care is “Medic Aid” and this occurs only after the most intense part of the battle has subsided. What does this mean to operators? Regardless if you are “Joe Citizen,” a soldier or a cop, you will be on your own for a few minutes and you will need the knowledge and skill to assist yourself and/or your teammates. In Vietnam, there were an estimated 2,500 deaths that would be survivable with today’s Combat Life Saver training and tactics that soldiers receive. This change is long overdue.

Gloves are a necessary precaution against blood borne pathogens.

Critical blood loss, obstructed airway and tension pneumothorax from a perforating chest wound (yes, they all suck) are the “big three” injuries that commonly kill operators. Now, don’t get worried about all this medical jargon. If a Neanderthal like me can figure this out, so can you. As you begin to dig into what it takes to keep someone alive, it isn’t very difficult. Keeping them alive for an extended amount of time has its own more complex series of issues, but keeping them alive until the ambulance arrives isn’t too tough.

What is the main difference between the medical training in use during Vietnam and now? The application of tourniquets first is the biggest shift in the modern programs. Previously, medics were told that a tourniquet was a “last resort” and only to be used if there was no other option. While they were making unsuccessful attempts to stop bleeding with substandard bandages, the operator bled out. The medics were great, but the protocol was terrible.

Individual medical kits (also called blow out kits) have also greatly improved during the last few years. A “Blow Out” kit is designed to prevent immediate loss of life from a traumatic injury. A “first aid” or “boo-boo” kit is used for minor cuts and scrapes and is useless for life support. The first aid kits at your workplace are little more than a headache relief center. Nothing that will save lives is in that metal cabinet on the wall. The two should never be mixed together. You don’t need to dig through Band-Aids and Chapstick to find your life-saving tools. Anything that cannot be used to stop the immediate loss of life goes in a different pouch.

Movement is just as important after you are wounded as it is beforehand.

There are several blow out kits on the market and many of them are very good, but a few are terrible. I will share my thoughts on what should be in a personal trauma kit. We will use a femoral wound from a gunshot through the thigh as an example. This is a very common wound. I think there are some items that should be in every kit and one is a set of gloves to protect you from blood-borne pathogens. Since your hands are your best trauma tools, you will use them the most. Most likely you won’t put the gloves on to treat a teammate, but when you stop to help someone in a car wreck, wear them. A tourniquet should be in the kit and should be applied immediately.

In the past, there was much misinformation about the use of tourniquets and it still has a stranglehold on stateside emergency medical services. “But he will lose his limb!” is the biggest fallacy that has managed to live until now. The fact is that every day, tourniquets are used for as many as three or four hours on a regular basis for medical procedures. Applying tourniquets first is saving lives in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the harsh reality is that if you had the choice between losing a limb or losing your life, you would lose the limb. But you won’t lose your limb, and neither will your buddy. Put the damn tourniquet on and save his life.

The kit also needs some wound packing material like gauze. For deep wounds like a femoral wound from a shot through the thigh, you need something to pack in the hole so pressure can be applied to the artery from the topside via bandaging. You can use just about anything, but something relatively porous with a lot of surface area like gauze works best. After the wound is packed, you need to put on a bandage. My personal favorite is the “H-Bandage,” which is an absorbent pad sewn onto an elastic bandage. It has a heavy-duty “H” shaped anchor in which to wind the elastic around for a super compression. The H-Bandage applies pressure all the way around the leg, and pushes on the gauze, which is pressing on the artery. Hopefully the combination of the tourniquet and the H-Bandage will stem the blood flow.

What is “critical blood loss”? You can take many things to a gunfight—like more guns and more ammo—but taking more blood with you isn’t feasible. All the blood you have in you right now is all the blood you have. On average, we have six quarts of the oxygen-carrying fluid in our bodies. We “lose” a pint when we give at the Red Cross, and that isn’t a very big deal. As a matter of fact, we can lose an entire quart and still be in pretty good shape. The serious problems begin to occur when we lose more than a quart. When two quarts of the hydraulic fluid leak out of us, we have most likely lost consciousness. When we lose three quarts of blood or more, we expire.

Movement is just as important after you are wounded as it is beforehand.

You cannot swallow your tongue, but an obstructed airway can be caused by the muscles at the back of the tongue relaxing and blocking the airway. This is most common with unconscious people lying on their back. The simplest way to solve this is to roll them onto their side and allow gravity to do the work of moving that muscle. A good kit will have an airway. They come in two flavors: nasal and oral. The nasal type is preferred because it is less likely to cause a gag reflex on a semiconscious patient and, since one size will fit the vast majority of people, there is no need to carry several different sizes as with the oral type. Safety pins are useful for this as well and, even though it is bloody as hell, if necessary you can pin their tongue to their bottom lip to keep the airway open.

Tension pneumothorax is the accumulation of air under pressure in the pleural space. The pleural space is the area between your chest wall and your lung. When a bullet enters the chest, it makes a “valve,” so to speak, with the damaged tissues. When you breathe in, the valve opens and lets air in, but when you breathe out, it closes and traps the air. An early warning sign is that your teammate will be telling you he cannot breathe deeply. As the pleural space fills with air, the lung will collapse. No big deal, because you can breathe with one lung, but the real problem is that the pressurized air is now squeezing the heart and if a little more pressure accumulates, the heart won’t be able to pump against it, and your buddy will die.

A very late warning sign for tension pneumothorax is tracheal deviation. You will see the trachea pushed to the opposite side of the body as the wound. Something must be done immediately, and that something is putting a big catheter in the space between the second and third rib, which is known as the “second intercostal space.” Inserting that 14-gauge needle just about the third rib will most likely provide immediate results, and you might even hear air hissing out of it. Be aware that some companies won’t put a needle in their kit. Don’t buy that kit.

That brings me to my next point. If you cannot be trusted to carry a needle, you need to turn in your gun. We all know they both require training, and reading this article will not meet that requirement. I love it when I am told I shouldn’t talk about catheters and chest decompression because of “liability.” Reality Check: I teach good people to kill bad people, and anything else I do carries less liability with it. I have opened up a can of worms with this article and hopefully motivated you to seriously consider some medical training as tactical training if it makes it easier to swallow.

Get some medical training. Even a simple Red Cross first aid class is better than nothing. There are plenty of places doing two-day gunshot or immediate action medical classes, so do some research and pick the right one. Take this issue seriously and get yourself into a class. You can get plenty of free info about battlefield medicine at www.GetOffTheX.com.

I carry two trauma kits daily. One is for inducing trauma and one is for relieving it. Every soldier, cop, civilian contractor and armed citizen needs to have the skills and the tools to save lives along with the skills needed to take the lives he may be forced to take. You will find more opportunities to be a hero from saving a life than taking one, so put some training and gear for dealing with a medical emergency on your wish list—and don’t forget M.O.V.E.!

[James Yeager is a police officer with narcotics and training duties at his department. He is also the lead instructor for Tactical Response. Course information and schedules are available at www.tacticalresponse.com.]

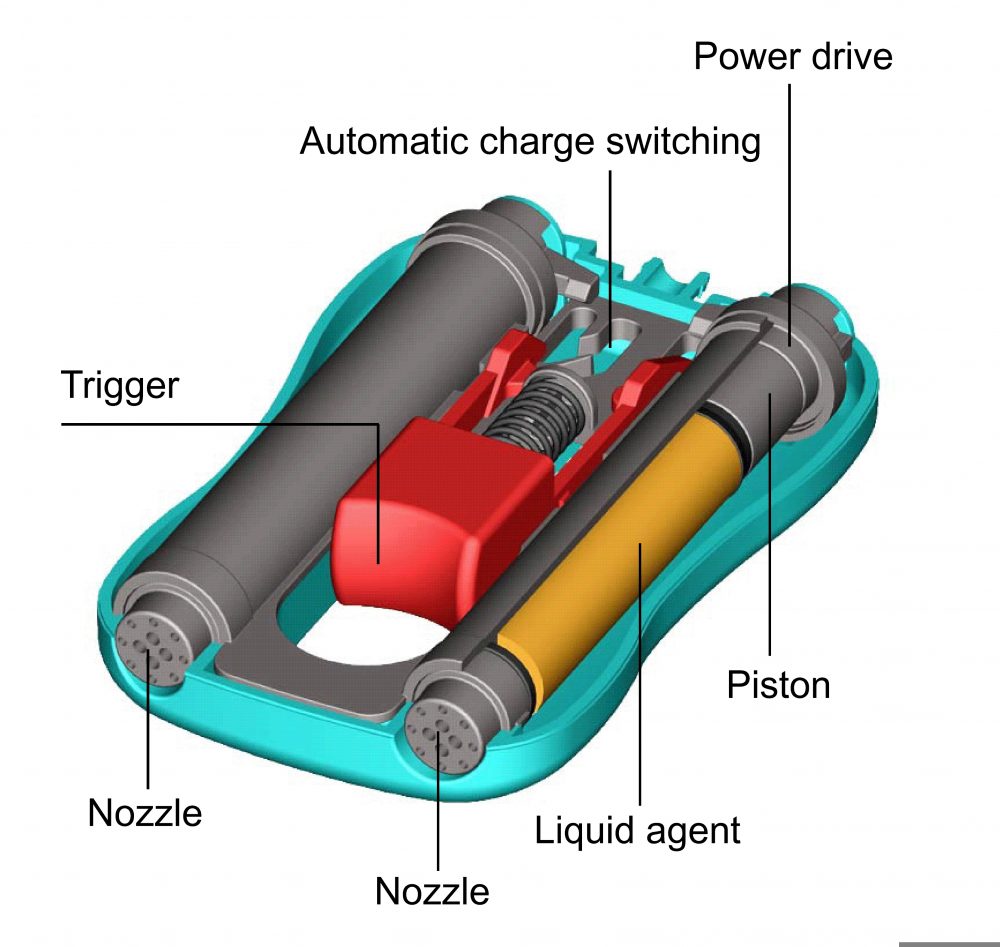

[Editor’s note: The author has created a “blow out kit” which can treat the above listed critical situations. Called Ventilated Operator Kit (V.O.K.), it is available at the Tactical Response on-line store. Cost is an affordable $30.00]

SOURCE:

Tactical Response Gear

Dept. S.W.A.T.

3350 Hwy. 70 East

Camden, TN 38320

(866) 822-4327

www.tacticalresponsegear.com