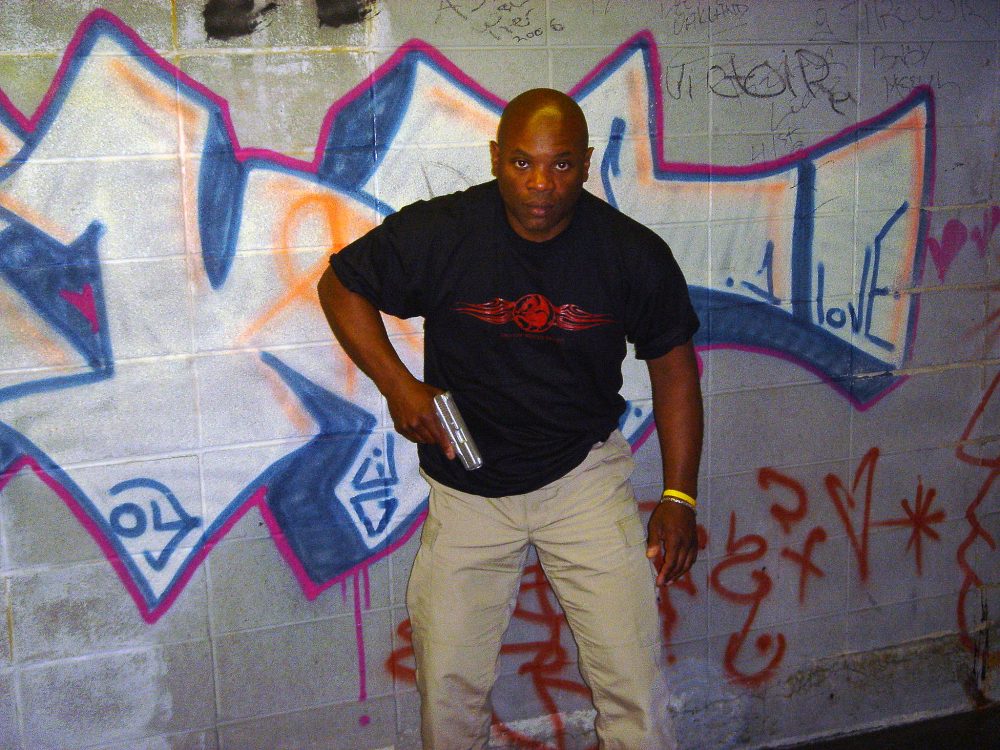

Large, frontally aligned target may allow “rougher” alignment of pistol on target.

What will it take for you to hit and stop your assailant in a deadly force encounter? Will the assailant be under the influence of extreme rage or drugs and hard to stop? Will one shot drop the suspect or will it take an entire magazine—or more? What will that encounter look like? Will it be at close range, 50 feet or even farther? Will you have a front, back or side shot? Will he be moving toward you or laterally or standing still? Will you be moving “off the X” as you shoot? All of these intangibles—and many more such as adverse lighting, innocent civilians in the background, etc.—must be prepared for in your training.

If we can’t say what your encounter will look like, then we can’t say what skills you will need to win the day. This is the case with the use of the sights on your pistol as well. For someone to say that you won’t use your sights because of the “fight or flight” response or that you shouldn’t need to see your sights to hit at close range belies the fact that you don’t know what you will need to do to “make the shot.” Since misses do nothing to aid in the fight for your life (indeed, misses compound your problems) and we can only count on decisive hits to stop an assailant, it is imperative that our rounds be on target. Further, on the square range, targets don’t move and innocent bystanders don’t get in the way.

Sadly, when it comes to using sights, we are subject to some people telling us what we will need to prevail, that misses are not a factor or that “any” hit will do. We must instead look at what it takes to hit and how we can correctly develop the motor skills conducive to winning a violent encounter.

Table of Contents

AUTOMATIC MOTOR PROGRAMS

According to movement expert Dr. Bill Lewinski of Force Science Research Center, a skill such as the presentation of the pistol from the holster, also called a motor program, must be practiced until it becomes automatic. Given a stimulus such as a suspect armed with a pistol or a knife, you must be able to draw your handgun without conscious thought to the process. Your grip and stance must be also practiced to the point that they are automatic. “Running the gun” must be second nature. Only by training to such a level can you expect to be effective. This includes sight alignment and sight picture.

The farther the distance and the smaller the target, the more attention must be paid to the sights.

The sighting process—bringing the pistol to eye level and aligning the front sight within the rear sight notch and centering that on the target—must be developed as a part of the drawstroke. The presentation presents the pistol to the target so that the sights are aligned. As Col. Jeff Cooper said, “The body aims, the eyes verify.” Oftentimes we have shooters who report that they “didn’t see their sights” in combat. However, Dr. Lewinski submits that if the act was an automatic motor program, in most cases you wouldn’t remember seeing the sights—you would do what you’ve trained to do.

Are there advantages to not bringing the pistol to eye level? The late Col. Rex Applegate, who himself advocated eye level shooting, suggested a continuum of shooting from one-handed “hip” shooting to two-handed eye level shooting with sights aligned. Col. Applegate believed that man has an internal clock and will shoot based on his perception of the time needed to bring the pistol to eye level. Applegate was not a fan of hip shooting, commenting that it was too inaccurate outside five feet, based on the inconsistent wrist and elbow bend.

If we accept that eye level shooting and sighted fire are the ultimate in terms of accuracy potential, anything less is what Applegate called “a compromise.”

THOSE BUMPY THINGS ON THE SLIDE

I grow tired of the whole point shooting issue. I’ve had to spend too much time fixing shooters who were told, “At this distance inward, you don’t need to see your sights,” or “Just shove the pistol out and fire.” (Some instructors even tape over the sights because students were referencing them while shooting.) Neither concept is conducive to good, accurate fire, and I’ve seen both fail in training scenarios and force-on-force.

“Collateral damage” is not acceptable in civilian self-defense or law enforcement. Unsighted fire in this scenario is a recipe for disaster.

Recently I had a range officer (I will not use the term instructor, because he isn’t) tell a shooter whom I had tried to correct, “We don’t teach flash front sight picture.” When I informed him that the majority of instructors do, he said, “We don’t teach that, we teach point shooting.” Question: If you don’t refer to the sights, how do you improve accuracy? Another co-worker said that these people believe it’s like the movie Star Wars: “Luke … trust the Force.” I’ve heard point shooting instructors say, “From 30 feet inward, you don’t need your sights.” Thirty feet? Well, that might work on the square range at a wide target that isn’t moving, but when these same students try it in force-on-force training, they fail.

Realistically, when should you use the sights? Whenever you perceive you have enough time. When should you use a “rougher” alignment, i.e., Applegate’s admonition to “shoot through the weapon system”? Whenever you perceive you don’t have enough time to do otherwise. When should you shoot at a hip, chest tuck or CQB position? When you believe you don’t have enough distance to extend or time to bring the pistol up higher.

THE OBJECT OF THE ENDEAVOR

The object of your gunfire in a deadly encounter is to score decisive hits on target—decisive hits that cause your assailant to stop or impair his attack on you. The most decisive hits in this context are, according to Dr. James Williams of Tactical Anatomy Systems™, the Mediastinum (upper center mass in the body targeting the heart and major blood vessels above the heart), the Lateral Pelvis and the Brain Stem.

These are specific targets, not just anywhere from topknot to toenail. Hits on these targets are more effective than shots elsewhere on the body and are aided by accurate fire. Accurate fire is aided by sight alignment, sight picture and trigger press. Alignment and sight picture are aided by an automatic (well-developed) stance, grip and presentation of the pistol from the holster. Start by developing the basics and work from there. If the suspect is close and you don’t perceive enough time, well-trained compromise positions can be effective.

Let’s stop telling students based on our biases what they will need in their gunfight, and instead develop shooters who can hit.

[Kevin R. Davis is a full-time police officer assigned to the training bureau. A 25-year veteran of law enforcement, he is a former Team leader and lead instructor of his agency’s SWAT Team. He welcomes your comments at [email protected] or visit his website at www.advancedtacticalconcepts.com.]