On the night of August 1-2, 1946, a group of American World War II veterans attacked their own county government with firearms.*

On a summer day in 1969, thousands of citizens of the tiny Soviet republic of Estonia simply sang a song. And sang it and sang it and sang it again until their befuddled Russian masters didn’t know what to do.**

If you wonder what these two events, separated by decades and an ocean, have to do with each other, read on.

POST-WWII U.S.

The government was corrupt in McMinn County, Tennessee. It had been for a long time. The wealthy Cantrell family had controlled politics there since 1932. Sheriff Paul Cantrell used secret ballot counting to ensure that he or his chosen candidates won every election. Law enforcement was routinely used as a tool to bring in revenues—something we now accept, but that was considered outrageous in those times. (McMinn County, under Cantrell and his successor Pat Mansfield, really did take it to extremes. For instance, they might stop a passing bus and charge all the passengers with public drunkenness, just to get a cut of the jail booking fees and fines. Bribery was also rampant.)

In 1940, 1942 and 1944, McMinn County residents had complained to the U.S. Justice Department about crooked elections. But the Justice Department did nothing. In July 1946, 159 McMinn County residents asked the FBI to send monitors for the upcoming primary elections. Again, the federal government ignored the locals’ pleas.

But by then, something had changed. Something big. About 3,000 GIs had returned to the county after the war—nearly ten percent of the local population. They were the ones who made the request to the FBI. They had organized a clean-government opposition to Mansfield and the Cantrell faction.

And no matter what the federal or state governments did—or didn’t do—they weren’t going to stand for corruption any more. They had helped liberate Europe and the Pacific from two monstrous tyrannies and didn’t figure they had to put up with tyranny at home.

August 1 was Election Day. Fearing the GIs, Pat Mansfield deputized approximately 200 armed cronies and set them to work, mainly in the county seat of Athens. Right away, the “deputies” started beating up GI poll watchers and giving trouble to GI voters. But the real crisis began to boil around 1500hrs, when a sheriff’s deputy told African-American ex-soldier Tom Gillespie, “Nigger, you can’t vote here today!” Gillespie insisted on his rights. Deputies beat him. Gillespie refused to yield; a deputy shot him. The shot wasn’t fatal, but the noise attracted a crowd, which spread the rumor that Gillespie had been shot in the back.

When it came time to count the ballots, Sheriff Mansfield had another trick up his sleeve. To make the vote count “public,” and therefore technically legal even if it was crooked, Mansfield “deputies” held two ex-GI poll watchers captive in a polling place. They’d be able to watch the crooked count, but not do anything about it. The two smashed a window and escaped. The increasingly incendiary crowd surged forward, and deputies surrounding the building pulled their guns. One threatened to kill anybody who came toward the polling place. For safety and secrecy, Mansfield then had all the ballot boxes carried to the county jail for tabulating.

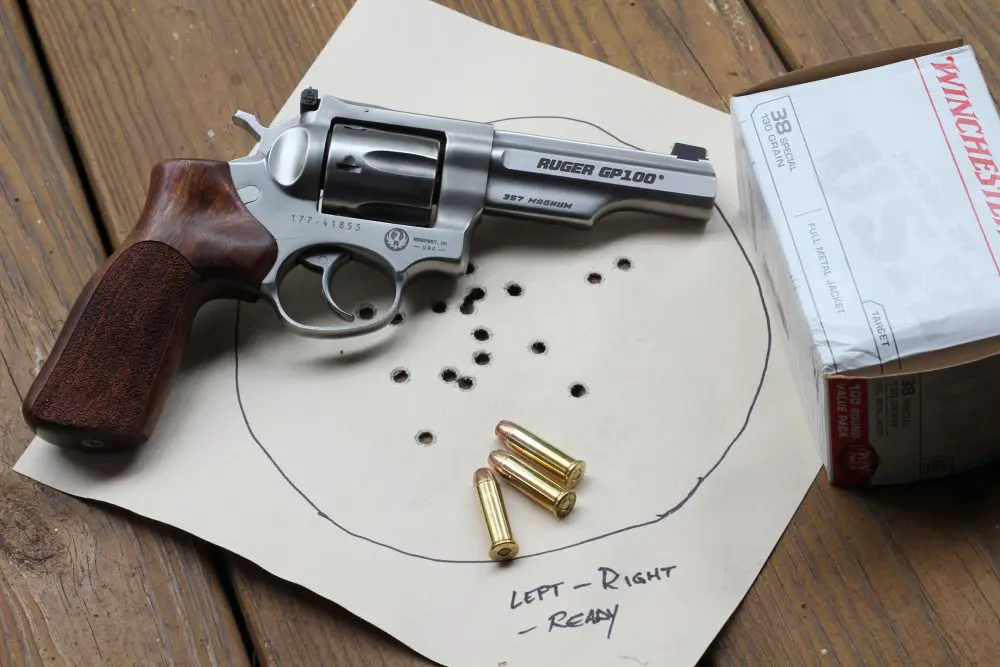

McMinn County didn’t have good government. But it did have the Second Amendment. Knowing they were about to get screwed once again, the ex-GIs hunted down every firearm they could. To supplement their own arms, they borrowed the keys to the nearly empty National Guard armory and borrowed three M-1 rifles, 24 British Enfield rifles, and five .45 pistols.

Around 2000hrs, the GIs and friends headed for the jail to take custody of the ballot boxes. They approached from the front, leaving the rear of the building open, hoping Mansfield’s people would flee out the back. Instead, deputies inside the jail began firing.

It wasn’t much of a battle. The heavy jail walls shielded those inside. The GI faction was disorganized. A few people on both sides were wounded, none fatally. After about 30 minutes, everybody started running out of ammo.

And there things stood. Tennessee’s governor mobilized the state guard with the intention of protecting McMinn County’s “lawful” government. But apparently fearing that his ex-GIs wouldn’t willingly fire on other ex-GIs, he never sent them.

Finally, around 0200, men on the GI side decided to break the stand-off. They threw dynamite at the jail, blasting away part of its porch. That was that. The deputies surrendered. The GIs secured the building and posted guards.

Later, they returned the meticulously cleaned firearms to the armory—and established cleaner government.

COMMUNIST EASTERN EUROPE

Twenty-three years later, a far worse tyranny held the tiny Baltic nation of Estonia. The Soviet Union had clenched Estonia in its steel grip since even before American GIs fought the Battle of Athens, Tennessee. The Soviet rulers had wiped out as much as 25 percent of Estonia’s population, outlawed the Estonian language and aggressively moved Russians into the country. In fact, officially there was no country—it was just one more Soviet Socialist Republic.

The one million Estonians had nothing. They were poor. They were oppressed. They were unimportant to the rest of the world; none of the great powers of the globe had any interest in helping them get free.

And, of course, they didn’t have a Second Amendment to codify their right to self-defense.

The one thing they did have was music.

Estonians, apparently, have always maintained a relationship between music and politics. Their country has been overridden repeatedly throughout history. But instead of becoming servile to or homogenized with their conquerors, they’ve used music to maintain their cultural identity. Song helped them resist German invaders as far back as the 13th century, and again to strengthen them against Russians who invaded under Peter the Great in the 1700s.

In 1869 they established a monumental song festival called Laulupidu. Every five years, as many as 30,000 carefully auditioned and well-rehearsed choir members take to the stage at the festival grounds in Tallinn and sing astonishingly beautiful music. The festival has always been about Estonian identity as much as it is about singing.

And so, on that day in 1969, when the choirs committed the revolutionary act (mentioned at the top of this article) of singing one particular song and refusing to halt, in a way it wasn’t surprising. But think of it. Here’s a tiny, battered and defeated nation, totally under the control of one of the two most powerful, brutal organizations on Earth. And right before the eyes and ears of the very masters who’ve been murdering them and deporting them to Siberia for years, they say NO!

The song they refused to stop singing that day is called “Land of My Fathers, Land That I Love.” It’s not even a traditional Estonian song; it was written in 1947 to the words of an old poem. But immediately it became the unofficial Estonian national anthem. So of course, the Soviets forbade them to sing it. At Laulupidu that summer, the choirs had obediently sung songs in praise of Lenin and Marx. They sang the glories of central planning and the Soviet Union. But when it came time to end the festival and leave the stage, spontaneously the thousands and thousands of singers and the thousands more in their audience refused to go.

They began singing “Land of My Fathers, Land That I Love.” They sang it again. They sang it as their masters ordered the orchestra to drown them out. They sang it as their masters frothed and foamed and threatened and tried to shut the festival down. They went on singing it and there was nothing anybody could do to stop them. There’s a recording of this moment and you can hear and see it. It’s awesome.

It was a beginning. That day, Estonian singers planted a small seed of a tree that wouldn’t bear fruit for almost 20 more years. Estonians went on being miserable and oppressed. The Soviet Union liberalized a bit over time. The worst horrors ceased, though life was still poor and constrained.

Then, in 1987, the tree finally bloomed. Something happened in Estonia between 1987 and 1991 that is now called “The Singing Revolution.”

From the perspective of the 21st century, we know that by the late 1980s, the Soviet Union was weakening within. But nobody had any idea at the time that the all-mighty USSR would topple if given a hard enough push. As it turned out, people in Hungary, East Germany, Latvia, Lithuania and other Soviet republics supplied that push. By 1991, a world superpower was gone.

Tiny, weak Estonia was one of the places that pushed hardest. They did it without arms, without a single killing, without battle, without any one strong leader, without any central organization. They did it in large part by singing. Now it wasn’t just tens of thousands of people singing their resistance, but hundreds of thousands gathering in spontaneous, defiant song. (And remember, this is in a country of only about a million people!)

Estonians found their courage, asserted their identity, restored their own culture, waved their outlawed flag and non-violently resisted their masters. The vast, brutal military power of the Soviet Union simply wasn’t able to confront them on the terms the “weak” Estonians established.

I’m not going to go into the details of exactly how The Singing Revolution overcame Soviet might. The Powers That Be at S.W.A.T. would like it better if I didn’t take up half their magazine ranting about a rebellion in an obscure foreign country. But there’s a DVD documentary called (no surprise) The Singing Revolution. You should see it. Particularly the final half hour. You’ll be cheering by the end.

So do you see how the Battle of Athens, Tennessee, and Estonia’s Singing Revolution are the same at heart? Americans fought using the weapons that came naturally to them: firearms. And a couple of well-placed sticks of dynamite. Estonians, disarmed but possessing centuries of musical tradition, fought with what they had. Both fought from their own strengths. Both won.

And both possessed the same spirit of rebellion. The spirit praised by Thomas Jefferson. The spirit that often seems lost in America these days. The spirit to resist tyranny—no matter what, and no matter how.

*Information on the Battle of Athens, Tennessee, is from the now out-of-print book The Battle of Athens by C. Stephen Byrum, Paidia Productions, Chattanooga, Tennessee, 1987. Thank you to Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership (www.jpfo.org) and The Constitution Society (www.constitution.org) for keeping the story alive.

**Information on “The Singing Revolution” is from a variety of sources, but primarily the film The Singing Revolution by James Trusty and Maureen Castle Trusty (www.singingrevolution.com), which can be purchased online or rented from Netflix.