When we consider our forebears’ traditional harvest resources, we see that common trees are a cornucopia of good food that’s free for the taking.

Trees have always supplied essential good things to eat, from fruits to nuts, but the tree itself can supply wholesome—and tasty—sustenance to more than beavers. Few people chew on tree parts other than a toothpick, but when it comes to suitable groceries, there is a lot more to a tree than just wood.

In case Con Agra and Wal-Mart stumble, it’s good to know about easy food that’s outside of controlled channels. The good news is, like the ancients understood, tree food grows all around us.

Some of the most common and widely distributed trees, for instance pine and oak, have fed millions in times past. The primary reason they don’t today is that these wholesome products, except for fruits and nuts, just aren’t a handy fit for supermarket supply lines. But who cares about merchandising considerations when we’re just looking for something good, and free, to eat that can be pulled directly from nature’s larder, without robbing or owing anybody?

Table of Contents

MORE THAN FRUITS AND NUTS

Aficionados of gourmet cooking, especially Italian specialties, love pine nuts, but you may have to talk to an elderly Scandinavian farm cook to learn of other pine tree parts that have been a staple food for centuries.

Since prehistoric times, Scandinavians and other northern Europeans relied on tree bark, the cambium layer especially of pine and birch, as a culinary staple. This continued through the 1800s, only waning after development of reliable cereal grains like rye.

In Finland, its use never died out, and was revived to save millions from starvation in modern periods of famine and wartime shortage. It’s making a comeback today, not to ward off starvation, although that’s always an option among cognoscenti, but because it can be tasty, and new research indicates it’s particularly healthy.

There are over 100 species of pine, like this Scotch pine photographed in Poland. The predominant pine of northern Europe, its inner bark has fed millions of people for thousands of years. All pine phloem is edible, as are sprouts and flowers and seeds, some of which form a decent-sized nut. Photo: Plepl2000, via Wikipedia

Native Americans also relied on birch and pine bark, particularly in the winter, because it was always there. “Adirondack” in the Mohawk-Iroquois dialect refers to Algonquians, who collected bark as staple food.

Good tree food includes not just pine bark, but other tree parts as well. And not just from pine, but also birch, maple, spruce, box elder, oak, and mesquite.

NO, DON’T LEAVE IT TO BEAVER…

There are more than 100 species of pine, so it’s a food that grows everywhere. The inner cambium layer (phloem) is the greatest and most widely used resource.

Archeological evidence indicates the people we now call Swedes have always eaten it. In the 1700s, botanist Carl Linnaeus observed that livestock eating pine-bark bread in the Nordic countries grew fine—but he bemoaned the widespread deforestation caused because bread made of ground bark instead of grain was the basic universal peasant food.

As a routine harvest, large sheets of bark are removed in the spring when sap is rising, and it’s most nutritious and easily peeled. The phloem can be eaten fresh. It was usually dried or roasted, then ground into flour and put away as a staple food with a long shelf life.

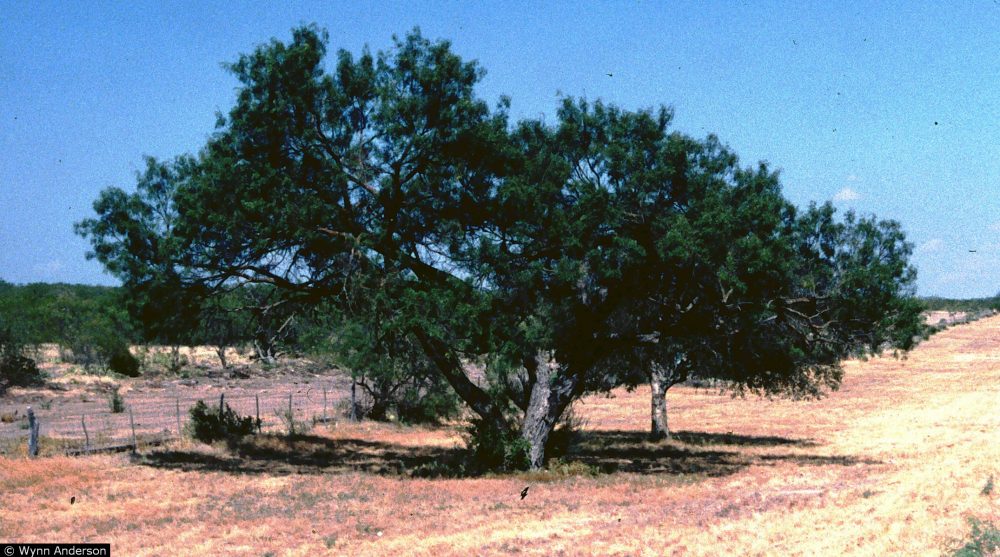

In the pea family, mesquite, such as this honey mesquite in Texas, thrive in arid areas and produce edible beans. Photo: © Wynn Anderson @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

There are regional tools and methods. Finns use a special hardwood tool, a lusa. Swedes used an iron tool, and in spring the whole family hit the woods like locusts to lay in a supply, so a grain or potato crop failure in the fall wouldn’t mean starvation.

The phloem may stick to either the tree or the inside of the rough bark when that is removed, depending on the season and species. The Finns usually remove the rough outer bark, then remove the phloem in thin sheets. They call the flour pettu. It is used alone, or to make other starch components go farther, such as rye flour in bread (pettuleipä), or as a thickener in soups and stews. Fresh strips are high in vitamins A and C, with fewer calories than grains.

When bark flour is substituted for grain, proportions can reflect how much, if any, cereal flour you have. In high proportions, it may taste best when you’re hungry. My palate likes it fine up to about 20%.

When they had no grain at all, the Finns just mixed pine bark flour with buttermilk and made a hardtack called silkko. Finns survived the great 1860s famine on stocks of pine bark flour laid in from previous years.

Classic acorn of the ubiquitous oak. These photographed in Texas represent food for all. Photo: Benjamin Bruce, via Wikipedia

We had Norwegian friends when I was a kid, and nobody who made biscuit-type breakfast rolls with pine flour was starving. If you think coffee smells good on the cold morning air, you should smell Vera’s pine biscuits baking in a Dutch oven!

By weight, young white pine needles contain five times the vitamin C of lemons. Swedes make a tasty herbal tea called tallstrunt from them, or they can be chewed and spit out. The resveratrol they contain is being studied for various health benefits.

Chippewa Indians used pine phloem as dressing for infected wounds, and pine tar has been a remedy for internal parasites.

Spruce buds also are high in vitamin C, are edible and make a tea with a bitter citrus flavor. They’re also good seasoning for gamey wild meat.

Young staminate pine cones were stewed with meat by Ojibwe Indians. Pine’s pollen-covered flowers are decent grazing if you have water to wash them down.

FOR MORE THAN BUILDING

Silver and other birch are all over northern Europe, and some 15 birch species are native to North America. Birch sap, containing 1% sugars, is a common drink in northern Europe. Birch sap makes good syrup, like maple. But the food staple from birch is the phloem, used for centuries to make flour, second only to pine.

Swedish scientists have discovered health benefits from bread containing bark meal, particularly birch. Cell Metabolism recently ran an article suggesting that betulin in birch may be as good as, if not better, treatment for hypertension and high cholesterol than existing medicines.

The history and use of birch bark parallels pine. The flavor is milder and more nut-like. Harvest is the same. They can be combined or substituted individually for grain flour. The more bark flour you use, the more leavening you need, and the more crumbly loaf bread will be from lack of gluten.

Consider flatbreads and hardtack if using large proportions of bark flour—if bark is all or most of what you have, flatbread may be easier. And you can always eat it raw or use it as a thickener in other dishes.

Here’s a foolproof modern Swedish recipe for flatbread you can bake soft like a pita, or hard like traditional Scandinavian crisp rye. A creation of Swedish baker Ingrid Ölund, it is a good one to test-drive how bark tastes:

Mix a quart of rye flour, 1½ quarts of wheat flour, ½ cup or more of bark flour. Mix a couple cakes of yeast in a quart of warm water, then blend in, kneading well. Let rise, covered, for an hour. Roll out small rounds on a floured surface, about saucer sized and ¼-inch thick. Lightly sprinkle with water and poke vent holes. Bake on a dry iron skillet or lightly greased or floured sheet for about ten minutes at 440F until brown at edges.

For pocket bread, don’t poke holes and bake at a lower temperature for a shorter time. Times vary with size and thickness. Crisp flat bread is traditionally made with a hole in the center and stored on sticks.

For off-the-grid sweetener, aside from the usual fruit goodies, keep in mind syrup and sugar from birch, maple, and box elder (also a maple).

MESQUITE BEANS

Here’s an easy sweetener if you live in the Southwest. Mesquite beans may be the easiest tree food except fruit. Pick dry from the tree, wash then simmer about a pound all day in a gallon of water. Strain. Boil it down to syrup consistency for “mesquite molasses.” Dark and flavorful, it has a pumpkin twang, and you can jazz it up with cinnamon. Its hearty flavor is great on flapjacks.

You can grind or pound mesquite beans, pods and all, for good meal or flour. Pods are fibrous, and the beans—actually peas—are hard as rocks. You can pound the pods off and boil them for good mush. It’s easier to coarsely mill the seeds before you boil them, or it takes forever, but like red beans, they must be cooked.

Flour milled from the whole bean is tasty, the sweetish pods balancing the slightly bitter beans. This flour, or a coarser meal, substitutes very well for most any grain—wheat, corn, rice—as long as you don’t need the gluten.

For excellent tortillas, mix 1½ cups wheat flour with ½ cup mesquite flour and ½ teaspoon salt. Cut in three tablespoons oil, then mix in ½ cup warm water and knead well, then let rest, covered, for half an hour. Roll into a dozen balls, flatten these to 1/8 inch and cook on an iron skillet or hot rock for a couple of minutes. When lightly brown, do the other side for a minute.

Mesquite meal also substitutes well for corn in most recipes, and makes a good addition to soups and stews.

THE MIGHTY OAK IS MIGHTY GENEROUS

Most folks are aware that some acorns are edible, or are edible as a survival food if you leach them, but few in modern times have deigned to try them. That’s a pity, because those who tally up such things (and I always wonder if it was done on a government grant) say that throughout history, more acorns have been eaten than all the rice and wheat combined.

Even though some oaks can produce more than 1,000 pounds of acorns a year, and some produce for more than 1,000 years, the problem is that they don’t work well as a commercial crop today, because for the most part they do have to be leached free of the tannin they contain. But in the broader view, it’s a minor hassle.

There are about 600 species of oak classified. All oaks produce acorns. All acorns are edible when tannin-free. This means that like pine and birch, oaks are a food source you are likely to find all over but not recognize.

Like the oak trees that bear them, acorns come in all sizes and shapes. All wear a hat and all are edible. Photos: Steve Hurst @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Archeological evidence indicates that, although never raised as a crop, acorns have always been a staple source of people food. Like people, some acorns are more worth the hassle than others.

In general, acorns from white oaks have less tannin, and the Emory oak of Texas and the Southwest is usually edible with no leaching at all, like any other nut.

Acorns come in all shapes and sizes, but they all grow out of a turban-like “hat” or capule. No capule? Not an acorn! They often fall free of the capule and look like a filbert lying on the ground, but if it is an oak tree, there will be capules on the limbs or ground. This is a primary identifier, since oaks vary from nearly 40 feet around and as big as a house, to small desert shrubs.

All acorns are arranged the same, and because they are, we’ll deal with them the same, although some are easier to make tasty. Some acorns grow in a season, some take two years. Some oaks never drop all their leaves, some drop every fall—but acorns, once ripe, are all good food. Harvested and dried, like other nuts they can keep in the shell for years under proper storage.

Step one is to dry and shell them. Some, like Emory oak, may be edible right then. For most, you next have to leach out the bitter and unhealthy tannin. If they’re big with lots of tannin, I’ve found they leach better if crushed or coarsely milled. If milled, your job is easier if you keep them in a cloth, but you can leach in a pot (no iron or copper) and strain them. Smaller ones can be put in a sack or cloth bag and left in a clean running stream for one day or several.

Tannin content varies widely, as does the number of leach cycles. If using a pot, use hot but not boiling water for about an hour. Exchange the water once or twice (occasionally more), repeating until the water comes out almost clean and the acorns have no bitter taste—only a nutty flavor with a sweet aftertaste. Tea and coffee also have tannin, just less of it.

Some acorns wear a “t-shirt” under the shell, which you remove. If you quickly dunk them in water after they’ve dried, this rubs right off. They vary: do as necessary. It’s a minor hassle.

When tannin-free, acorns can be roasted, milled and used like any nut, but can also be used in the place of grains for breads, as a thickener in soups and stews, or alone as a great mush.

As a staple and not a novelty food, acorns have fed millions for thousands of years. They are highly nutritious. Try them as flour for raisin cake, heavy breads, and the like. You can grind sample batches in a little spice mill, or use any kitchen grinder for larger quantities. Keep flour refrigerated. And enjoy!

When a blue-haired matron at the Woodsman, Spare That Tree rally gushes, “Don’t you just love trees?” you can say, “Yes, ma’am! Baked and boiled, mostly. Wanna trade recipes?”

DON’T BARK UP THE WRONG TREE

Not all bark is good food. Experimenting with bark that doesn’t have a history as food might be dangerous. Willow bark is an analgesic and blood thinner. Chittum bark (cascara sagrada) is a powerful laxative. Many spices come from bark—but so do tannin, resins, latex, medicines, poisons and hallucinogens. And if you have food allergies, test even proven tree derivatives sparingly, as you would any new food.