The slide-action 12-gauge shotgun is the archetypal American long gun—the everyman’s universal tool that is equally useful harvesting edible game or definitively stopping a fight. The two classic “pumps” are the Remington 870 and the Mossberg 500 series, and I have trained extensively with and enjoyed each.

I have the utmost respect for the unique ballistic capabilities of the “gauge,” having seen its ability to remove meat and bone at common fight distances. Advances in shotgun chokes and shells have significantly improved already impressive versatility. A specific area of improvement has been in defensive buckshot rounds, with low-recoil offerings that use improved wads to extend practical range and maximize impact.

With the above in mind, I share a personal concern: I have never truly trusted the pump shotgun in my hands for serious business. (Gasp!) Even more heretical, I have actually begun to consider a semi-auto 12 gauge a more appropriate choice.

Before you inundate the editor with passionate rebuttals and demands for a retraction, hear me out. First, if you rely on a pump gun and are happy with it, do so in good conscience with no complaint from me. Its track record is proven and if you are comfortable with it, you are carrying a lot of gun into the fight.

Second, I recognize that there are “training issues” that can resolve any of the concerns I have. The reality is that the mindset you bring into the fight, backed by solid instruction and regular practice, more than offsets equipment shortcomings. But the rub is that many acquire a shotgun in order to bypass training and practice.

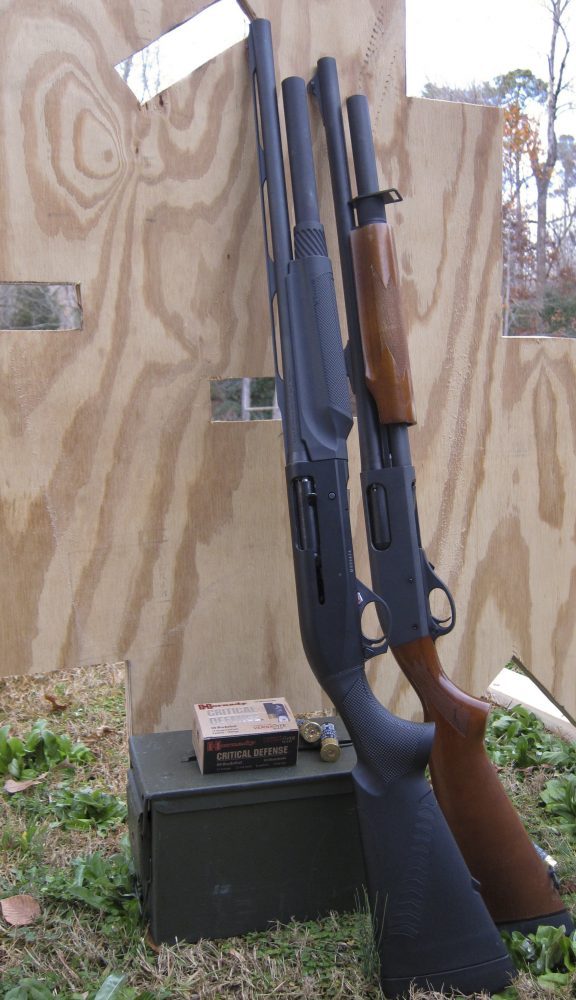

Pump shotgun is a true American classic. Shooters may let nostalgia interfere with a critical look at its capabilities.

Table of Contents

WHAT’S MY BEEF?

On to the issues. The pump shotgun is perhaps the most cost-effective weapon available anywhere. For the cost of a secondhand service pistol or less than half the required outlay for a service-grade AR or semi-auto 12, you can acquire a new 12-gauge pump gun.

Because of this, and its universal use and effectiveness in American law enforcement, we often assume that the weapon is also the most appropriate or that other options are inferior. The iconic nature of the 12-gauge pump makes any questioning of it tantamount to an assault on other symbols of American manliness, such as the 1911 or John Wayne movies.

It was this bias that hindered me from recognizing my distrust sooner and connecting years’ worth of dots. I have trained with some of the best shotgun names in the business and earned paychecks training fighting men on the shotgun, and I slowly realized that numerous sacred cows had lined up for slaughter. These were reliability, speed into action, and suitability for the novice.

For experienced users, 870 remains a suitable choice, but shooter may benefit from a fresh look at pros and cons relative to semi-auto 12.

RELIABILITY

The perceived strong suit of the slide-action shotgun is its reliability. Your definition of reliability matters greatly. Here we are speaking of the capability of the shooter to consistently place multiple shots without interruption. The weapon is only as reliable in this definition as the shooter’s capability to run it. There are two primary faults and they are both the shooter’s faults, not the shotgun’s, but the results are the same.

One is that the shooter must remember to cycle the action in order for the shotgun to be a repeater. I have seen a wide variety of aggressive men fail to cycle the action after a shot, particularly if presented with a single target. In some cases, the omission is completely missed by the shooter until the next target is presented. With many, it may only be a delay that presents as an action (the shot), the reaction (it worked/didn’t), then recognition that they forgot to rack on recoil and the decision/correction. This takes a portion of the shooter’s faculties and devotes them internally on problem solving rather than externally on the situation.

The second fault is the tendency for shooters to short stroke the action. This is where the shooter fails to either run the forend all the way to the rear before returning to accomplish the ejection and feeding/chambering, or fails to return it all the way forward to lock the action. More often it’s the failure to run the action all the way to the rear, resulting in closing the action on an empty chamber. I’ve had it happen an embarrassing handful of times myself and have watched it occasionally bewitch users at all experience levels.

Semi-auto shotgun’s bolt is as easily cycled as shotgun is retrieved as racking action on the slide-action, allowing both to be stored safely yet ready for action.

It is undeniably a training issue, but it happens frequently enough to acknowledge and consider whether in a given shooter’s hands, the weapon is truly reliable. Since I am less brilliant and dexterous under stress than on my best range days, the short-stroke issue is a concern that in the “suddenly awake and processing threats” home-defense scenario, I may not remember to run the bolt all the way fore and aft.

By comparison, I recently trained a group on Benelli M4/M1014 shotguns and, like every other group I’ve experienced, not a single shooter failed to sufficiently cycle the bolt to chamber the initial round. Further, as they processed scenarios, there were none of the slightly frazzled “trying to remember what to do” looks that you see with pump-gun trainees. They simply pressed shots to send buckshot into targets. The skill transfer from years on the M4 made the jump to the shotgun a simple one of adjusting to a low-capacity tubular magazine.

A discussion of mechanical reliability in the semi-auto shotgun requires specificity. Quality dedicated service auto-loading shotguns with quality defensive buckshot or slug loads are a different discussion than your buddy’s mass-market hunting gun with bargain multi-purpose shells that hiccups and sputters through each three-gun match.

Working action on recoil is acquired skill that takes practice and focus to manipulate weapon at speed. Many less experienced shooters struggle to run action reliably as part of recovery, particularly under stress.

SPEED INTO ACTION

One perceived strength of the pump gun is its ability to be stored or transported with the magazine tube full and chamber empty in complete safety, yet readied for action in the motion of mounting the gun.

It occurred to me that this ease is probably overstated in some cases relative to cycling the bolt on a semi-auto shotgun, so I set up a simple test. I took two shooters, one an average shooter with basic familiarity on the 870 but no formal training, and the other an armed professional with significant formal training.

Neither had any experience with the Benelli M2 used against a well-broken-in 870 Express. The drill began with the shotgun’s chamber empty and a round of Hornady Critical Defense 00 Buck in the magazine tube. On the signal, the shooters retrieved the shottie as in grabbing from a closet or trunk, and chambered the buck while presenting to and engaging an MGM steel silhouette at ten yards.

The Remington was in modified Condition 3, meaning the hammer was down on the empty chamber, unlocking the action so the shooter had only to cycle the forearm. The Benelli had the shell on the carrier to allow the shooter to similarly only cycle the bolt without pressing the shell release lever.

Interestingly, across a number of repetitions, the times were nearly identical with each shotgun, averaging 2.55 seconds (pump) vs 2.49 (auto) for shooter one and 1.62 seconds for both with shooter two.

The gap widened significantly when shooter one attempted the drill with the action locked on an empty chamber, with over eight seconds required to find and press the action release and then complete the drill under the time pressure. The experienced shooter required 2.13 seconds—an additional half-second—to unlock the action.

Modern semi-auto shotgun simplifies application for shooters, allowing them to take advantage of reduced recoil and rapidly press shots, maintaining focus externally on the situation rather than on operating the gun. Note ejected shell in air and bolt closing on another shell.

SUITABILITY

As simple as a pump-action gun appears, the first drill presented an interesting data point when the first shooter short stroked the 870 on his initial attempt. The time was thrown out, but it surprised him how easy it was to make the mistake. His experience level, however, far exceeds the many first-time buyers who are given the go-to advice of, “Get a 12-gauge pump for defending the castle.”

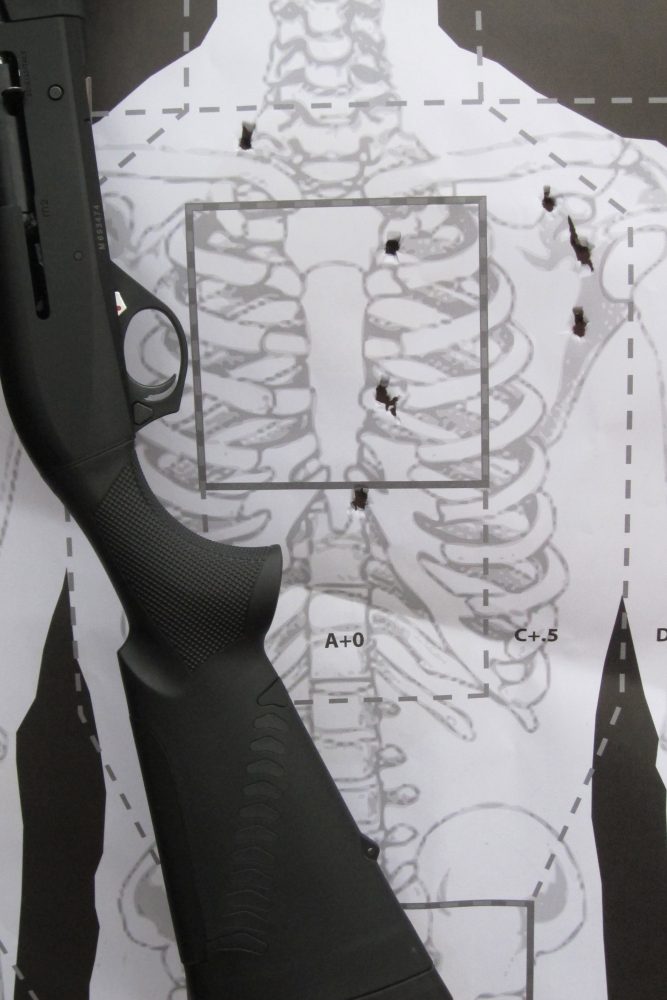

The shotgun is often touted in the multiple-adversary role, due to the speed allowed by coarse aiming and multiple projectiles. An additional drill was set up to measure the time for multiple targets with each shotgun, the drill beginning from the ready with shells chambered against six targets at ten yards.

The time for the basic shooter to engage all six with the 870 averaged about nine seconds, with an occasional miss from attempting to go too fast. The average time to cycle the action and acquire the next target was 1.54 seconds. Over a second and a half is not ideal in such a situation, allowing ample time for an aggressor to orient on the preceding shot, decide and act on it. Switching to the Benelli, the time dropped by nearly half, with the shooter averaging 4.99 seconds with no misses and the split time between targets at .73 second—much better suited to take on a pack.

After a few repetitions of this, there was no contest which weapon he was more comfortable with, strongly preferring the ease of semi-auto operation.

The more experienced shooter posted .65 second splits with the 870 and nearly halved those to .36 with the unfamiliar Benelli. Being able to service three separate targets in barely a blink over a second with 00 Buck is serious close-range capability. The ability to simply recover from the recoil and swing to the next threat to press the trigger on another payload is not only faster, but it often allows better hits because the shooter is moving less than when working the action and driving to the target.

The self-loader has the additional benefit of converting energy that is recoil on a pump gun into work, cycling the action and reducing the push on a 12 gauge. The degree of difference varies by the exact semiautomatic system in use and the load, while the overall benefit is relative to the experience and recoil sensitivity of the shooter. The experienced are able to translate this into mostly speed, where the less so are able to turn the recoil reduction into better control, more external focus, and a faster response to follow-up shots.

Like other classic American fighting guns, the slide-action shotgun is going nowhere anytime soon. Long familiarity, reputation, and cost will ensure it remains one of the pre-eminent home defense choices. However, it won’t be my first choice.

There were several chapters in my life when I relied upon single-action revolvers for my defensive weapon without hesitation, and that was fine, but it doesn’t mean I would choose one over a modern service pistol for general duty today. Likewise, if I want the unique capabilities of the shotgun, I will be reaching for a modern service semi-auto 12.

HORNADY CRITICAL DEFENSE 00 BUCK

The shotgun is wonderfully versatile. Sporting versions have long offered removable choke tubes to allow the shooter to tailor the spread of the shot pattern to the target or quarry.

In contrast, the riot gun of whatever make has more often than not sported an improved cylinder barrel to provide near maximum spread at close range. While this improves hit potential slightly at seven to 15 yards, targets beyond that range pose a problem.

The shooter cannot guarantee that the full payload will strike near point of aim. And for every yard distant, the donut effect kicks in, with the pellets often dispersing in a ring around the aim point and potentially off target.

For years the only solution for a concerned shooter who wanted to get 25 to 30 yards out of buckshot before doing a select slug drill was custom work to get a Vang Comp or thread the barrel for choke tubes. There are now defensive loads available that allow the effect of a full choke in a wide-open tube.

Hornady Critical Defense loads employ the Versa-Tite wad to control dispersion of the shot. The shells also drop one pellet from the conventional eight-pellet payload to keep velocity optimized for penetration and semi-auto cycling while reducing recoil. This is winning on both ends, with increased speed and control with low recoil at the shoulder and the ability to extend range and precision at the target.

The loads tested here threw a roughly seven-inch pattern right to point of aim at 25 yards with a wide-open choke—an equivalent pattern to what milspec 00 loads produced at seven yards. Straight magic. This gives the defensive shotgunner choke-tube-like choice simply by selecting standard or Critical Defense buckshot.