For our purposes, mechanical offset relates to the difference between the line of bore and the line of sight. This distance will vary from one gun to another. Additionally, the sight and mounting system will also influence the difference. All handheld firearms have a certain amount of mechanical offset. It may be negligible in the case of a pistol, or significant in the case of certain rifles/carbines.

This article will limit the discussion to carbines and focus specifically on the AR family of weapons.

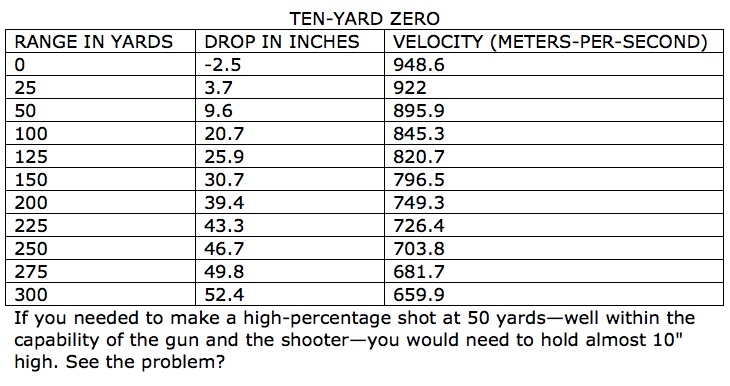

Generally speaking, the iron sights are approximately 2.5″ above the bore line. Optical sights may vary in height above bore. For the M16/M4 family of weapons, it is 2.5″. For optical sights mounted on a flattop receiver, the line of sight may be slightly higher or slightly lower than 2.5″. If that sight is mounted on top of a carry handle, it may be significantly higher.

Now that we know what offset is, we need to know why it is important to us.

Let’s delve into the world of exterior ballistics for a moment. When you are looking at a target, you are looking directly at it, in a straight line and no matter the distance. Be it six inches or 600 yards, there is no ballistic curve to your vision.

However, when you press the trigger on your favorite bullet launcher, that projectile is not a beam rider. And it is—as are we all—subject to gravity and friction. As soon as that bullet leaves the muzzle, gravity and friction jump in and start slowing it down, while at the same time causing it to head downward toward the deck.

If you were to drop a bullet from a mechanical device and fire a bullet of the same weight at the same time from a barrel that is parallel to the deck, both would strike the deck at the same time. (It is a fact. I saw it on Mythbusters.)

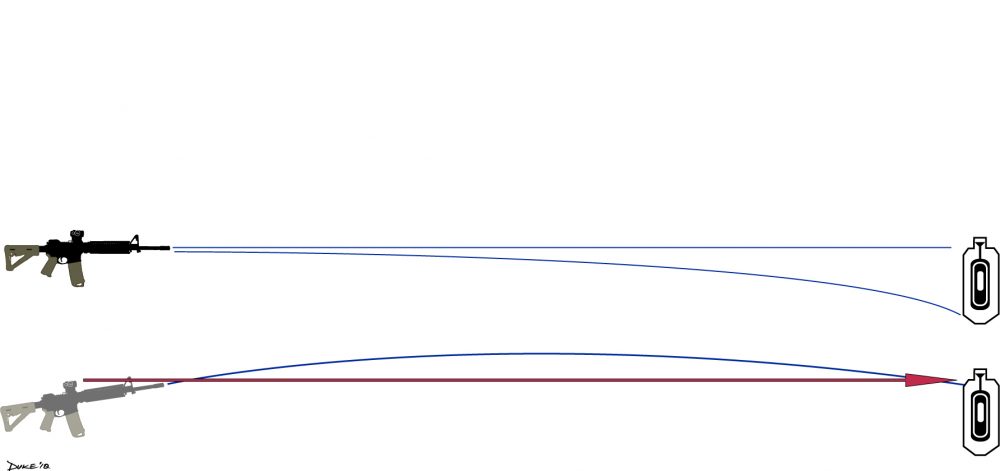

So, if I want to start here and hit a guy square between the nipples at 200 yards, I have to elevate the barrel slightly in order to overcome the effects of gravity and friction.

And we accomplish that elevation by adjusting the sights.

As the muzzle will always be that (approximately) 2.5″ below the line of sight, the barrel will have to be elevated in order for the projectile to sail away to that distant target.

Please understand that the bullet doesn’t automatically fly high as it leaves the barrel. It moves upward because that is the direction that the barrel is pointed.

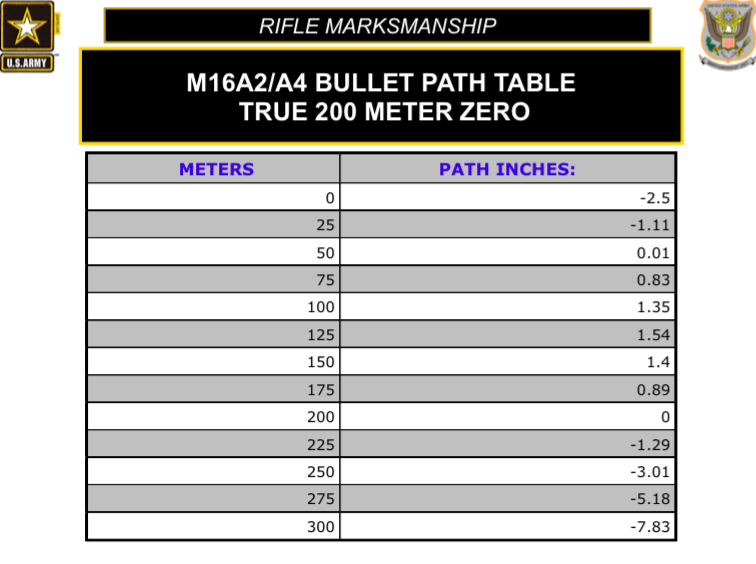

Using an M4 carbine and M855 ball, that 62-grain bullet will move up to -0.87″ at 25 yards, and continue to +0.43 at 50 yards, having crossed the line—the initial intersection of sight—a few inches earlier. At 100 yards it will be at +1.94″ and at 125 yards it will reach its maximum ordinate—the highest it will be above the line of sight. It will continue to describe that arc until it crosses the line of sight at 200 yards (commonly the zero distance).

So, if I wanted a center mass hit (considering this to be the upper chest) from contact distance (-2.5″) to 250 yards (-3.88″), all I need to do is hold right between the nipples.

This is sufficient for engaging a human threat with a carbine—we are talking about infantry engagement here.

Let’s switch hats for a minute. Instead of being a Grunt, you are now part of a Direct Action Element or police tactical team tasked to rescue a hostage. This is Close Quarter Battle, and by definition CQB requires surgical shooting.

The perp is on the other side of the room, maybe ten feet away. He has a BFK (Big expletive deleted Knife) to the throat of a baby that he is holding in front of him. The infant is partially obscuring his lower face.

From training, you know that if you introduce a supersonic velocity projectile directly into his brain housing group, it will cause him to immediately cease all functions.

Knowing this, you want to place that bullet where it needs to go, and the center of what you have available is right between his running lights. You swiftly put that red dot right there, right in between those two skuzzy eyeballs, and press the trigger straight to the rear. The bullet screams out of the gun and covers those ten feet in .0036 second—and strikes the kid right in the cruller, 2.5″ lower than you intended and causing his demise. All because you neglected to compensate for offset.

If, however, you place the dot 2.5″ above where you want the projectile to strike (at that same ten-foot distance), the bullet will enter the mutt’s head, penetrate his skull and turn the interior of his cranial vault to mush, causing him to cease being an earthly oxygen consumer.

Which result would you prefer? Killing the infant or killing the perp and saving the kid’s life?

Understand that offset is an issue only up close. At 25 yards, it is less than one inch, which in the overall scheme of things is insignificant. The closer you get to the target, the more significant it becomes.

Consider that within ten yards, it is very significant (see above).

Mechanical offset is built in. It is not a recent phenomenon—it has always existed. It is just that true CQB has only been with us since the 1970s, and most people are not that clued in to near contact distance shooting.

Mechanical offset is not that difficult either to understand or master. And if one does have issues with either, maybe it is time to consider a career change.

Every so often, some well-intentioned stud will say, “Hey, the FBI (genuflect) states that most police shootings take place at seven yards and under. Why don’t we just set zero at seven or ten yards and then we don’t have to compensate for offset?”

Why indeed?

Average does not equal reality. A few years back, we had a midwestern SWAT team in an EAG Tactical class. They presented the argument that “since we are a SWAT team and we do entries, any shootings we get involved in will likely take place at under seven yards. Therefore if we zero at seven yards, we can dispose of all the holdover nonsense.” When I pushed them to tell me where their shots would be at 50 or 100 yards, they were unable to tell me.

Karma is a bitch, and as we were walking out to fire our initial zeroing rounds, the team was activated for a shots-fired call. When they returned, they advised that they had chased the skell down in a cornfield. While no shots were fired during the collar, distances varied from 100 yards down to near contact as the shiny things were placed on the perp’s wrists.

They changed their SOP to a 50/200 zero on the spot.

They are not alone in this thinking. Several years ago, a Regional Tac Team from a prestigious Federal agency wanted to do the same thing.

There are several issues with this as an SOP.

The first is common sense. If anyone really thinks that all of their future gunfights will be at seven yards or under, they are spending too much time in a parallel dimension. You can no more choose the distance at which a fight occurs than you can make an appointment to have an emergency. And limiting yourself to a seven-yard zero only increases the complexity of the situation when engaging a threat at a greater distance than you are prepared for.

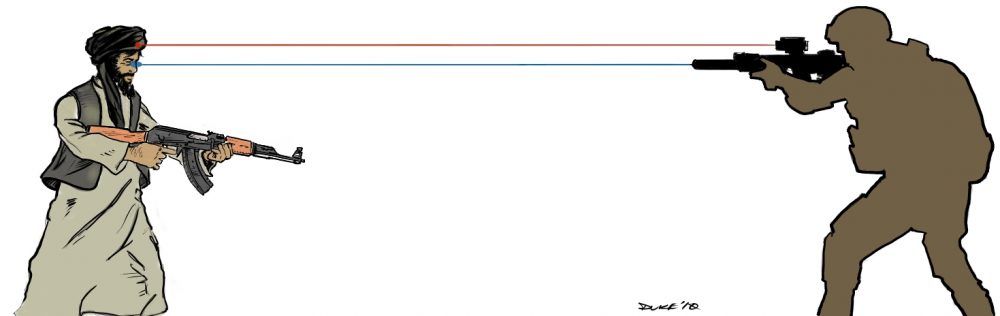

Another, more insidious problem with the seven-yard zero is the “Officer Friendly,” “community policing” or “it can’t happen here” crew. In case one hasn’t noticed, we are at war, having been attacked way back in 2001. This war is ongoing, and not likely to end in our lifetime.

In 2008, the enemy launched a successful attack on Mumbai, where ten terrorists killed at least 166 people, shutting down the city for three days. The Mumbai police were woefully ill-prepared for this attack, and there are a lot of police administrators and politicians in this country who have their brains inserted firmly within the fourth point of contact if they think it can’t/won’t happen here.

How would your cops do if they had to engage even a moderately trained but properly equipped paramilitary crew that was shooting your town up? Would you be able to deal with suppressing the fire of a shooter who had the high ground advantage 200 yards away? Would you know where to hold?

Of course, additional questions might be asked about your training, ammunition load-outs, resupply and so forth, but hey, why complicate some administrator’s life?

Offset is neither new nor is it difficult to deal with. It does, however, require that you understand what it is and when you must compensate for the difference between the line of bore and the line of sight.

On another level, it also requires that you understand that what was normal nine years ago is not the same normal as today. The word “average” does not apply to gunfights, and the potential for more serious threats to be visited upon us by our enemies is not a matter of if, but when.

You have to understand that your training cannot be geared to what has happened in the past, but rather what may happen next month, next week, tomorrow or in three minutes.

You have to train to that worst-case scenario, and that in fact may mean that your mission has just been flushed down the porcelain receptacle.

When some administrator, politician or trainer states emphatically that it will “never happen here,” remind them that never is a long, long time.

[Pat Rogers is a retired Chief Warrant Officer of Marines and a retired NYPD Sergeant. He is the owner of E.A.G. Inc., which provides services to governmental organizations and private citizens. He can be reached at [email protected].]