I was recently chatting with my next-door neighbor, Kirk.

“Hey John, Diane is home from college. Want to come in and say hi?” “Sure.”

I followed him into his house. The scene inside immediately put me on the defensive. Sitting at the kitchen table were Kirk’s wife, Vicki, and their two college-age children, Steve and Diane. Vicki and Steve were trying to comfort Diane, who was extremely upset and agitated.

“Her boyfriend dumped her,” Vicki explained, triggering a wave of sobbing from Diane.

“Hi, Diane, what’s going on?” I asked.

“I’m just going to shoot myself,” Diane announced hysterically. She grabbed a pistol and waved it around with no regard for muzzle discipline.

Vicki lost her composure, and now they were both wailing uncontrollably. I moved off the line between me and the muzzle of Diane’s pistol, drawing my own gun at the same time and pointing it at Diane.

“C’mon, Diane, put the gun down now!” I yelled firmly. More wailing and threats of suicide from Diane, who then dropped the pistol on the table amid hysterical sobs.

Vicki, who was near hysteria herself, retrieved the pistol, but before I could breathe a sigh of relief, she started waving it around, oblivious to the fact that my front sight was now superimposed on her chest. In my best schoolmaster voice, I instructed her, “Vicki, put the gun down now!”

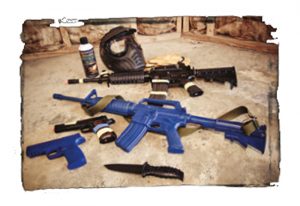

At that moment, instructor John Farnam blew a whistle to bring the exercise to a close. I holstered my Airsoft pistol, and my three friends seated at the table stepped out of their fictional roles and went back to being assistant instructors in Farnam’s Defense Training International two-day Force on Force class.

Table of Contents

DEBRIEF

John Farnam began a short debrief of the exercise:

What did I see when I walked in? What made me behave the way I did? And for me, the biggest question was, what made me decide not to shoot a person who was pointing a gun at me (regardless of whether it was aimed unintentionally and without malice toward me) and instead spend a few moments bobbing and weaving to avoid looking down the muzzle?

The same scenario was played out with each member of the class, with Farnam tweaking the behavior of the instructor/actors so that students could not react based on previous versions of the same scenario. Some students simply left the scene at the first signs of wild emotional behavior, while others shot it out with the actor.

The Suicidal Family Member was one of several interactive role-playing scenarios where the student was challenged to be observant, correctly evaluate the unfolding situation, think quickly, and then act to fulfill the ultimate goal of preserving their own safety. In some cases, this meant simply walking away. In others, it meant aggressively and decisively shooting until there was no longer a threat to them or a third party of injury or death.

After that first drill, my adrenaline level was way up. Why was I hesitant to shoot an hysterical college kid who, with a twitch of her trigger finger, was half a second from (hypothetically) blowing me away? After all, I’ve hunted enough animals, from prairie dogs to elk, to know I can make the shot.

And while I was amped up emotionally in the drill, part of my brain was still telling me I was only shooting a plastic Airsoft BB. Additionally, every person taking part in the drills— actors and students—wore protective face masks and eyewear, gloves, and a couple layers of clothing to prevent any injury more than a mild sting from the plastic pellets.

However, another part of my brain was also telling me that after all the years I’ve spent on real shooting ranges firing real guns in a safe manner with my friends Kirk, Diane, and Vicki, even shooting them with Airsoft went against the grain. I decided I wouldn’t make that mistake in class again.

DINNER AT THE RESTAURANT

The Dinner at the Restaurant scenario involved three actors sitting at one table and another actor, “the wife,” sitting alone at the table next to them. The first couple of iterations of this drill involved a single student walking into the restaurant to meet his wife. The other table starts to get rowdy, and one of the actors brandishes a gun she’s just bought at a gun show. The student politely directs the actor to put the gun away for safety reasons. She complies, and the drill is stopped.

In a later progression of the same scenario, I was sitting at the table with my “wife” when a masked gunman walked in and announced a hold-up. I had my back to him, but as I turned to look at him over my shoulder, he looked away. I got up, turned toward him, drew my pistol, and issued a warning. He turned toward me and I shot him to stop the threat.

In the debriefing, John Farnam asked me why I didn’t shoot him sooner. Good question. The “robber” had already signified he was a deadly threat by brandishing a gun and announcing that he was robbing the place. I needn’t have waited for him to be looking at me before I defended myself. This scenario illustrates why we train with instructors who truly understand the dynamics of the law and violent situations.

By now I had no qualms about capping any of the actors whenever I thought it was appropriate. Sorry, guys. I mention this because, like all good training, the scenarios we played out in class were designed to be as close to real life as safely possible. They combined awareness, observation, decision-making, course of action, and controlling our wide-ranging and complex emotions.

WHY ROLE PLAYS?

Statistically, in a real-life violent encounter, the odds of actually shooting a person are 30:1 against. That would be more comforting if we could predict which incident of those 30 was the shooting incident—the seventh, nineteenth, or thirtieth? Instead, we train to be flexible in our decision-making.

Pretty soon after that first morning, I think most students realized that surviving the scenario without being shot or having to shoot was more of a victory than launching controlled pairs of BBs into the center mass of our assailants. Almost any shooting is likely to at least result in arrest, and possibly arraignment, trial and prison; not to mention a civil lawsuit resulting in expensive lawyer fees at best and damages at worst.

It makes walking away from a situation without having to draw a gun a pretty good alternative, although there are no guarantees that will always be the outcome.

This is why we train in tactical roleplaying scenarios. Having said that, it’s worth noting that, while some students chose to walk away from the suicidal college student scenario—a sensible option in real life—they deprived themselves of an opportunity to learn from their mistakes by getting more involved in that training exercise. Class is where we have the luxury of learning from our mistakes without any real-life consequences.

We learned that in any tactical situation, we need relevant information in order to make a decision. In many situations, the best option is to disengage and separate, but it is dangerous to relax too soon—are there other threats? Flashlights often aid us in information gathering, and although it won’t be complete, information is a valuable component of achieving our goal, which is to avoid getting hurt.

VEHICLE SECURITY

Sitting in a stationary vehicle makes us vulnerable. We ran various shoot/noshoot scenarios with two students in the front seats of a vehicle and our badguy actors walking in front of, behind or even up to the driver’s side window.

One technique used by street criminals is for a woman holding an infant to push the baby into the arms of the driver and then rob him while his hands are full. How many people are likely to push the baby back at her? If communication is deemed necessary, it doesn’t have to be through a fully open window.

In an actual shooting, John Farnam explained that rounds fired into a vehicle are less effective if the vehicle is moving than if it’s stationary. Pistol bullets are the least effective, followed by 5.56mm. Shotgun slugs are more effective than most other rounds. Many rounds will be trapped in the engine compartment or will skip off the windshield, depending on the angle at which they hit.

TAPE LOOPS

There is an old saying that if the only tool you possess is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. Clearly, shooting a nonviolent panhandler who just wants us to toss him a couple of quarters is not in our best interests. Instead, we develop a simple phrase to make him pause long enough for us to disengage.

“I’m sorry, sir, I can’t help you!” gets the message across.

However, if the panhandler escalates the situation to violence, we might respond with violence to survive it. A running commentary helps witnesses to establish a timeline for the police.

“Officer, I heard that woman yell repeatedly at her attacker that she couldn’t help him, and to leave her alone, but he wouldn’t quit. Eventually she had to defend herself.”

Several times during the class, John Farnam reminded us that when we loudly tell a person who is accosting us in public to back off, we are also talking to any potential witnesses. “STOP! DO NOT MOVE!” Bang! gives a better description of the incident for a witness to relay to investigating officers than if all the witness hears is, “Mumble, mumble,” Bang!

“I dunno, officer, he may have said, ‘I’m gonna get you!’ and then I heard a shot….”

Committing various “tape loops” to memory can be very helpful when under great stress, such as in the immediate aftermath of a defensive shooting. We were taught when the police arrive to say, “Officer! Thank God you’re here! I’m the one who called. Those people tried to murder me. I’ll be happy to answer any questions once my lawyer gets here—and sign a complaint.”

Yes, it takes time and practice to commit these statements to memory, but it certainly beats trying to explain what happened while our blood pressure is at 500 psi, breathing is labored, and our brain is in information overload. “Officer, I got that sucka before he could get me” isn’t exactly something you would want to explain to a prosecuting attorney or an ambulance-chasing land shark in a civil court case.

As John Farnam explained, “Most of these scenarios will be far from perfect. The fact that you live through it you can consider a victory, but it’s not going to have a happy ending.”