THE Smith & Wesson J-Frame Airweight .38 is probably the most carried and least fired handgun out there. There’s a reason for that.

The recoil is beyond what most people will willingly subject themselves to. This is a shame, because the little revolvers shoot well with some practice and effort, but are notoriously difficult to shoot well without same. A used JFrame is rarely a bad bet, and few are shot beyond a box or two of ammo. Mine is a notable exception.

Here are a few things to consider to get more out of the J-Frame experience.

Table of Contents

BLEEDING IS BAD

When I upgraded my snubbie to a new 642 a few years back, I took it to the range with the then-new +P 135-grain Short Barrel Gold Dots to see where it hit. At the first shot, I had a distinct sensation of pain in the web of my hand and some scuffing on the skin of my thumb’s first knuckle—but the hit was good.

Too stubborn to quit, I fired the rest of the cylinder. By the fifth shot, there was a nugget of flesh stuck in the checkered teeth of the cylinder release latch and my thumb was oozing O positive. My palm was smarting a little also, at a distinct but manageable level of discomfort. I swapped over to standardpressure loads and fired a few more to get a better feel for the Smith, and then moved on to other tasks with other weapons.

As soon as I could, I took a Dremel to the latch and worked it over. I ground and ground until there wasn’t a single full sharpness diamond left and I could slide the inside of my thumb firmly up and down over the part without any roughness, knowing that recoil was going to do the same with more force behind it.

I left one small corner of dehorned diamonds at the upper quadrant of the part to facilitate operation of the latch. It’s worked beautifully. I try to avoid filing or grinding on my weapons as a rule, but this was a must-do situation. Firing a handgun should not involve getting scratched or cut by your own equipment.

Of course, the J-Frame is so petite, and hand sizes and placement of grasp are so variable that another shooter might never be affected by the same part. However, if an edge or part is biting under recoil, I seriously consider smoothing it out. You wouldn’t keep driving your car or truck with a sharp burr on your steering wheel that scratched you every time you turned the vehicle.

On some edges or in extended practice sessions, masking a suspected “high spot” or edge with electrician’s tape can provide relief. If the tape makes a difference, consider dressing the edge.

BEST THING TO EVER HAPPEN TO THE AIRWEIGHT

I like lasers on handguns in some applications. They are a good fit on the JFrame to offset the modest sights and short radius, particularly in low light. However, the Crimson Trace LG-405 is a godsend for the Airweight shooter.

The laser is actually a bonus for the package, with the greatest value in the grips being the compressible filler over the backstrap. The grips allow me to get higher on the gun than I could comfortably and consistently before, providing more leverage against recoil. The padded backstrap makes a world of difference in taking the sharpness out of the recoil directed into the web of the palm.

I don’t understand why Smith & Wesson hasn’t switched over to a laserless version of the LG 405 as the standard OEM grip—it’s that good. The grip doesn’t add to the profile of the revolver much, but gives a great grasp on the J.

HORSEPOWER

I’ve carried a wide variety of loads in the .38 Special snub. Prior to the changes above, my default was standard-pressure loads. With the improvements, I often tilt toward +P loads, but try to be mindful of where I am practice and sustainment- wise.

On more than one occasion, I have downgraded the carry loads to compensate for a lack of range time and sustainment. I place a premium on being able to run the snub well at a brisk speed, more so than having marginal control over the revolver as it tries to buck out of my hand.

This is highly subjective, and every shooter has the ability to tailor the level of recoil with load selection. There is a wide spectrum in available .38 Special loads. Generally speaking, there are two mechanisms to reduce recoil. The first is to choose a lighter bullet (assuming an equivalent velocity). The second is to push the bullet more slowly. This presents some choices to the shooter along with some trade-offs, particularly if the shooter wants penetration and expansion.

Bullet weight assists penetration, with the traditional 158-grain weight for .38 service revolvers penetrating well. But launching that heavier mass has an equal and opposite reaction in your palm and in muzzle rise. The nominal velocity at 158 grains standard pressure is marginal for reliable expansion, even from a service-length barrel. With a snub tube, additional velocity is lost, challenging expansion in most conventional standard-pressure loads.

As a rule, I assume that a standardpressure hollow point in .38 Special is not going to expand from a snubbie. It might, but it has beaten the odds if it does. With this in mind, the shooter is free to choose lower velocity/lower recoil loads like the 148-grain wadcutter, which will cut a full-caliber profile while penetrating well.

There are newer bullets specifically designed for short barrels, such as the Hornady Critical Defense FTXs, which have taken the necessary construction, mass, and velocity to expand at standard pressure into account, and these typically sacrifice mass for velocity, which decreases penetration relative to the non-expanding projectiles.

At +P levels, the shooter is able to gain mass and velocity in an expanding bullet, with the newest designs providing a reasonable guarantee that the bullet will penetrate to the required depth while expanding as designed. The price is recoil.

RECOIL AS TIME

Many shooters look at recoil in terms of the pain or discomfort it causes. This is balanced by the piggybacked notion that the pain is bringing more terminal performance. Pain is subjective; what bothers me and exceeds my threshold may only inspire confidence in you that the bullet will thump a threat.

Time is not subjective.

I wanted to measure the effect of recoil on the shooter’s ability to follow up by translating it into time. Recoil has to go somewhere: it either translates into time to recover the revolver or it turns into loose hits (or misses) as the shooter runs the trigger before the handgun is realigned with the target. Naturally, this effect is only relevant if the shooter needs multiple shots either to hit well or stop the threat or threats.

If you are counting on the first round to do all the work, then recoil matters only when it sprains your wrist. But for most carrying a J-Frame, the data provides a frame of reference and food for thought.

The 642 was shot against a rack of eight-inch steel plates at ten yards. The time to recover the J-Frame from its muzzle rise and trigger the next shot onto the succeeding plate provides a means to compare the recoil of different loads in practical terms.

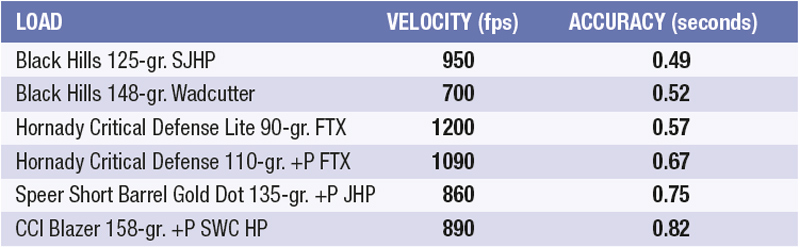

The plates were a stand-in for a threat’s vital zone and just difficult enough a target to ensure the snubbie was being recovered fully from recoil and truly controlled by the shooter while being run as fast as possible. Multiple runs from each load were averaged for split times (time between shots). The testing revealed a wide spread in average split times, from a low of .49 second with Black Hills 125-grain SJHPs to .82 second with CCI 158-grain +P LSWC HP. A third of a second difference is huge, demonstrating the wide range of recoil in .38 Special loads.

That time might also represent an additional incoming round, a solid step closer from a charging threat, or reaction time and movement from a dodging target.

In feel there was little difference between the 90-grain Critical Defense “Lite” FTXs (.57), the 125-grain JHPs (.49), and the Black Hills 148-grain wadcutters (.52). The additional speed of the FTXs brought the revolver back into the palm a little faster but with very little muzzle rise, while the wadcutters recoiled back sedately but with a good bit of rise. None were unpleasant. I would expect all but the frail to be able to control any of the three with a little effort.

On the +P side of the ledger, there was a distinct amount of sharpness in recoil as the bullet weight climbed from 110 (Hornady FTX/.67) to 135 (Short Barrel Gold Dot/.75) up to 158 (CCI LSWC HP/.82). For me, the 110 +P was manageable, the 135 getting sharp but tolerable, and the 158 a “no thanks” level of discomfort.

A standard caveat is in order. The split times here are representative of what I can expect. Your results might be faster or slower. I have more rounds through the Airweight than the average bear, and yet some of the recovery times to follow up to the next shot were painfully slow. The legion of casual concealed carry J-Frame toters is likely to be slower yet.

I suspect that, even if another shooter’s splits are double mine, the relationship among the different loads will either remain constant or increase as the effect of recoil on a less experienced shooter becomes more pronounced with the stouter loads.

HITTING

The 68-grain difference among the loads plays hob with fixed sights, and a shooter should factor that into the decision along with the recoil. A revolver is sensitive to weight changes and sight regulation, since the recoil is bringing the barrel upward even before the bullet exits the barrel. The heavier recoiling loads thus hit higher, and light loads may not elevate the barrel enough to reach the line of sight that is engineered toward a standard load.

In this particular revolver, the Gold Dots and Black Hills 125s shot right to point of aim at 15 yards, with the 110 FTX about 1.5 inches high. The 158s were far enough “off” to be a concern, while the 90 Lites struck about three inches low and the wadcutters three inches high. At more common defensive ranges, the variation is less noticeable. The point of impact issue is helpful in deciding among otherwise similar loads.

Another consideration that might weigh in on load selection is the bullet profile’s effect on reloads. I use Bianchi Speed Strips in conjunction with the J and, regardless of what is in the cylinder, the reload consists of a bullet that slides easily into the chambers. The new FTX bullets reload particularly well, while wadcutters are an exercise in patience and perfect alignment.

OTHER OPTIONS

The J-Frame equals Airweight .38 Special in most of collective shootingdom’s mind. Steel versions are out there and adding weight to the gun is another method of damping recoil, all else being equal.

Various .32 and .22 WMR revolvers that bypass unpleasant recoil by caliber are also on the market. On paper they’re a sketchy idea, but I’m not sure that many essentially untrained revolver shooters attempting to launch +Ps into a fight wouldn’t be just as well off with a lesser caliber that they are in control of.

If the shooter actually practices with the “pleasant” caliber, things start to look up even more. Whether the lesser rounds will effectively stop a threat is the issue that stirs debate and invites the .38 with low-recoil loads back to the table.

There is an additional data point worth considering. Shooting the 13- shot Smith & Wesson M&P9 compact on the same plate rack drill, my split times averaged .55 second with Black Hills 124-grain +P JHPs. So for a slight bit of additional effort in carry, the shooter gets significantly more capacity and terminal performance in a package that is more controllable than the Airweight with its most effective loads.

The J will remain wildly popular for a long, long time. Counterbalancing recoil can help the scads of Airweight owners become Airweight shooters.