Walk into any gun store and ask about doubleaction revolvers as carry guns. Chances are you’ll be directed to the J-Frame section. Any reputable shop will likely have at least a few of them stocked. Small alloy-frame five-shot revolvers offered by Smith & Wesson, Charter Arms, and Taurus (and Ruger’s polymer-frame LCR) have great appeal because they are convenient to pack.

They’re typically considered close to the bare minimum based on the .38’s marginal power and the little gun’s limited ammunition capacity. Judging by the popularity of these guns, lots of folks take the minimalist approach. Unfortunately, the virtues that make them easy to carry also make them difficult to shoot well.

The J-Frame checks the boxes next to the strongest suits of revolvers—simplicity and reliability. It has great merit as a deep cover gun when nothing else can be hidden or when weight is the major factor. I carry one in a small fanny pack when riding a bicycle, but it’s a second gun when I’m in street clothes unless the choice comes down to a J-Frame or no gun at all. A 642 in your pocket certainly beats a 1911 in your truck when you really need it inside the convenience store, but the J-Frame comes to the gunfight with multiple handicaps. The old K-Frame M&P does away with most of those handicaps.

Table of Contents

J-FRAME OR K-FRAME?

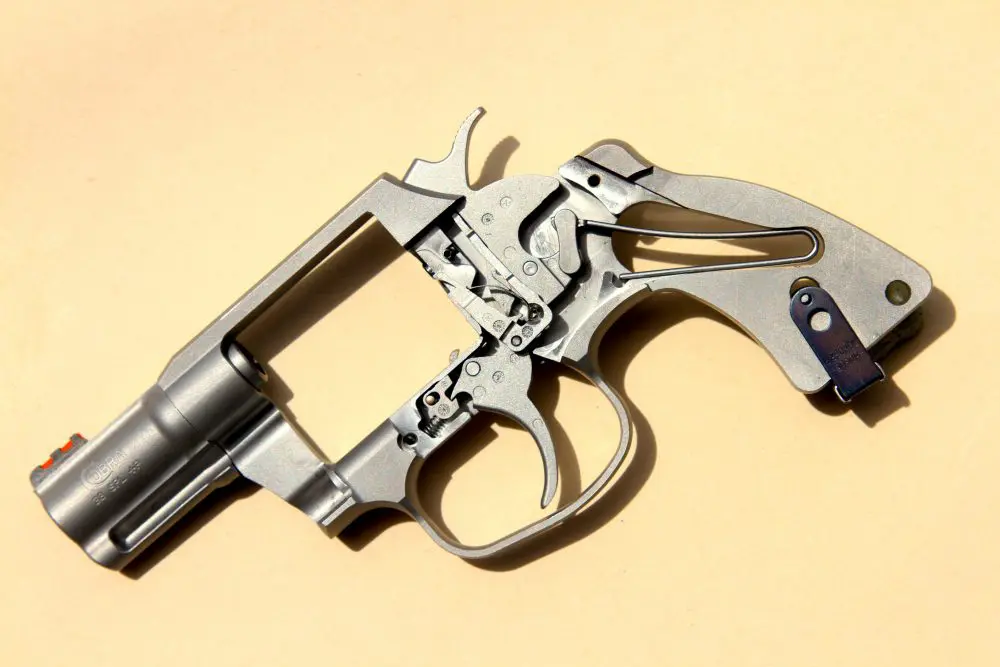

Obviously, the K-Frame holds one additional round of ammunition. With a revolver, one more is a big deal. The fulllength extractor rod standard with three-inch and longer barrels makes extracting and ejecting empties much surer and facilitates faster reloads. Extractor rod length is rarely a consideration when buying a revolver or shooting it for leisure. It becomes a huge factor when you need to reload with urgency. The slight size increase in the frame, cylinder window, and most of the parts makes the gun easier to manipulate overall.

A +P round that’s painful to fire from an alloy J-Frame is comfortable from a steel K-Frame with a three- or four-inch barrel. The larger size of the K’s grip frame provides more to hold onto and can be custom fit to the shooter’s hand with a choice of different stocks. Using stocks that trace the frame profile minimizes size for concealment.

Smooth wood or hard synthetic stocks allow cover garments to slide over them without catching or bunching up. It’s easy to swap for larger stocks with some recoil-absorbing cushion for extended shooting sessions or when hiding the gun isn’t important.

The 1⅞-inch barrel standard on J-Frames is a challenging laboratory in which to produce complete combustion with most powders. Really short barrels rarely achieve factory published velocities, even if the ammunition was developed specifically for short barrels. The longer barrels normally found on K-Frames produce higher velocity and more energy. This boost in performance nudges the .38 Special from marginal to acceptable.

The sights on most production J-Frames are pretty basic. The K’s longer sight radius and larger sights make delivering accurate fire more likely. The K-Frame’s mass around the moving parts makes the trigger pull feel better, even if the pull weight is identical to the J-Frame’s. Pulling the trigger doesn’t push the heavier gun around like it does the lightweight snub-nose.

While an alloy J-Frame may be as intrinsically accurate as its bigger brother, in practical application the big gun’s trigger is much more forgiving. Again, this equals better hits.

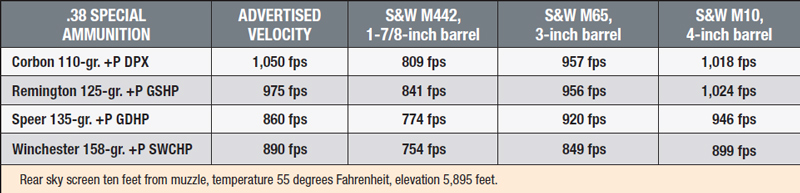

VELOCITY MEASUREMENTS

I recently measured velocities of four carry loads with common bullet weights in a J-Frame 442, three-inch Model 65, and four-inch Model 10. The average velocities from five-shot strings are listed in the table on page 78. The additional barrel length of the three-inch gun yields a huge gain in velocity over the J-Frame. The jump from three to four inches is not as dramatic, but still increased 50 feet-per-second (fps) or more with three of the four loads. If kinetic energy impresses you, the J-Frame likely will not.

Both K-Frames used were selected because they had fixed sights like the small gun. I fired through the chronograph screens using a bean-bag rest for support. While doing so, groups were fired on paper at 20 yards with each barrel length. Twenty yards may seem like a long way for a J-Frame, but is not an unrealistic range for a carry gun. Shooting supported slow fire isn’t particularly “combat relevant,” but the longer K-Frames sure shot better at that range.

RANGE DRILLS

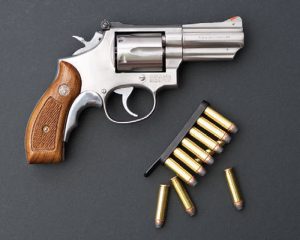

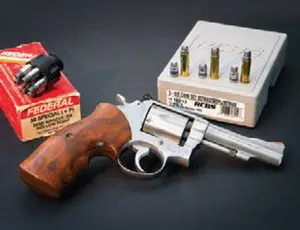

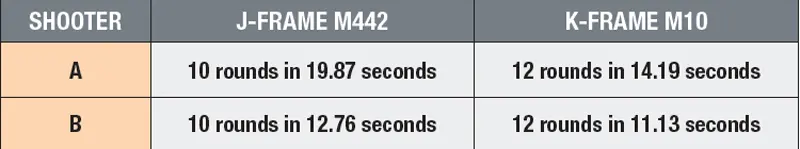

While on the range, I had two shooters familiar and skilled with revolvers conduct a simple impromptu drill with the 442 and the tapered barrel Model 10. The shooters drew on a timer prompt, fired until empty, reloaded with a speedloader, and emptied the gun again. Distance was five yards, using the same holsters and Safariland speedloaders snapped in a DeSantis pouch. Ammunition was the Remington 125-grain +P GSHP. I asked the shooters to make good center chest hits on a human silhouette.

Shooter A had drama on the J-Frame reload as the empties wouldn’t fully eject on the first attempt. He had to re-grip, strike the extractor rod again, and then pluck two empty cases out with his fingers. Shooter A established a sight picture for every shot and his groups showed it. All good hits, with the K-Frame group being significantly tighter.

Shooter B fired faster, but admitted to a flash sight picture on the first round and hammering away on subsequent shots, trusting his natural point of aim. Although not as tight as Shooter A, all hits stayed in the “A” zone of high center mass. Shooter B’s K-Frame group was better than his J-Frame group, but not by as large a margin as Shooter A.

Both shooters shot the drill faster with the K-Frame even though they were firing two more rounds than with the J-Frame. Both also showed tighter shot placement with the K-Frame. The J-Frame’s shorter extractor rod reared its ugly head for both shooters, as Shooter B also had difficulty ejecting empties after firing his second series of five rounds.

J- AND K-FRAME CHAMBERINGS

The fact that the J-Frame couldn’t muster 200 foot pounds of energy wasn’t lost on those who lobbied S&W to chamber the J for the .357 Magnum. You won’t find many people willing to argue against the effectiveness of the .357 as an antipersonnel round—it’s well proven.

But a lightweight J-Frame so chambered boosts recoil to an obscene level. Felt recoil is already one of the big negatives in a 15-ounce revolver chambered for the .38. The Magnum version is ridiculous. Smith builds lots of them to satisfy demand—they sell like crazy—but I don’t know anybody who shoots Magnums through these snotty little beasts for fun.

A steel-frame three-inch gun is the smallest size gun truly practical for the .357 if you actually plan to shoot it. The Magnum generates tremendous blast and punchy recoil, but it becomes tolerable in this platform with practice.

The K-Frame was originally designed around the .38. It wasn’t until 1955 that S&W improved their metallurgy sufficiently to handle

Magnum pressures. There’s a reason that Smith introduced the L-Frame in 1980. History proved that a habitual diet of Magnums was rough on a K-Frame. The L-Frame is hardier, but it doesn’t rate the title “readily concealed” for most people.

A .357 K-Frame in trained hands stands at the very top of carry gun choices, but there’s nothing wrong with .38 versions. The Model 10 M&P was the company’s bread and butter for most of the 20th century. Instead of supercharging the J-Frame with the Magnum, maybe maximizing the Special with a K-Frame makes more sense.

The Lyman 3rd Edition Pistol and Revolver Handbook says of the humble Special: “The .38 Special is accurate, has reasonable power and is easy to control, making it one of the most successful handgun cartridges ever.” Lyman used a four-inch barrel to test loads—the good

reputation that the .38 Special has earned largely depends on that barrel length.

The .38 Special is an easy cartridge to reload, straightforward and efficient. Commercial cast bullets provide an economical source for high-volume practice rounds. Keith bullets (RCBS 38-150-KT and 173-grain Lyman 358429) and 160-grain WFNs shoot really well in most .38s and can be driven 950 to 1,050 fps without beating up guns. The flat meplats on these great bullets hit hard.

Properly sized and lubed cast bullets generate less bore friction than jacketed bullets of the same weight. This equals more velocity and less pressure. The old FBI load (+P 158-grain SWCHP) had a pretty good record as a fight stopper back in the day. Older K-Frame fixed sights were regulated for 158-grain bullets, so the heavyweights hit where you aim them.

Cops used to shoot lead .38s in their Combat Magnums for practice and

save the 125-grain JHPs for duty use. This practice prolonged the life of K-Frames and helped officers build proficiency.

Fireside wisdom in the 1980s was to shoot a cylinder full of jacketed bullet loads through the gun after a day of practice with cast bullets to “clean out” lead deposits. Don’t do it! Many a K-Frame was unknowingly wrecked by applying this dangerous practice.

A non-yielding jacketed bullet forced down a severely lead-fouled bore can split the barrel where it protrudes unsupported into the cylinder window. Remove lead build-up in the forcing cone with a stiff bore brush or Lewis Lead Remover before firing jacketed bullets. The same tools can be used to clean the carbon/lead ring from the charge holes that develops when shooting lots of .38s in a Magnum cylinder. Left untended, this residue will eventually prevent Magnums from chambering until removed.

CARRYING THE K-FRAME

Yes, you sacrifice ease of concealment and light weight to bump up a frame size. But the gain in hit potential, ballistic performance, and handling qualities realized with the bigger gun may be worth compromising a little space and weight. A K-Frame carries best in a belt holster—either inside or outside the pants. A good gun belt and welldesigned holster go a long way toward stabilizing the gun and negating the extra weight. Shoulder holsters and offbody carry are options if these methods agree with you. Ankle carry and pocket carry are basically forfeited with the larger gun.

A three-inch K-Frame occupies roughly the same amount of space as a Glock 19. A bull-barreled four-inch version makes a footprint similar to a fullsize auto. Some may question carrying the revolver when the semi-auto holds much more ammo. An observation: large magazine capacity does not equate to winning gunfights. Shot placement does—particularly with handguns.

Suppressive fire as a tactic in most domestic encounters will be frowned upon in a courtroom. The old adage “if you only have six in your gun, you’re more likely to make them count” holds some water. M&Ps soldier on as legitimate personal defense weapons in our digital age because they work.

Clint Smith once wisely stated, “If everyone in this country had a Model 10 and practiced with it a lot, we would be a very dangerous nation, indeed.