An old lady is waiting out the afternoon heat under a shade tree. A small child is happily playing with a dog. Occasionally a car will pass by, greeting neighbors through a rolled-down window. As I stand here in the Central American midday sun, it is hard to believe that over 100 murders have been committed on this little street in recent years. But the murders have been committed—they are real— as is this San Salvador barrio and its gang problem. My partner, Jeff Randall and I are literally standing on the front lines between two of the most vicious gangs in the western hemisphere.

Much has been written in recent years regarding Salvadoran gangs. Primarily, there are two: the Mara Salvatruchas (MS-13 or just MS) and the 18th Street. The term mara is a Spanish word Salvadorans use for gangs. Salvatrucha is a nickname in Spanish for Salvadorans, particularly those Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN) guerillas that fought in the civil war throughout the 1980s. As of late, however, the nickname has come to have a broader defi nition. The term “18th” is reportedly derived from the street in Los Angeles where this Hispanic gang originated. (NOTE: In the U.S., 18th Street is sometimes referred to as MS-18, but not in El Salvador.)

Both gangs have developed particularly violent reputations, especially against one another. But then again, the people of El Salvador have a history of being tough. Their armed forces are currently deployed to Iraq and have distinguished themselves in some fi erce battles in and around the town of Najaf. The guerilla war that ended in 1992 was one the most brutal wars fought in Latin America. Many of these “kids” are products of that struggle and now fi ght their own brand of revolution. Due to the intricate multi-dimensional structure of gang alliances in the U.S., the two Salvadoran gangs, although rivals, do not share the same animosity in the States that is so often displayed in their native country of El Salvador.

Jeff and I recently traveled to El Salvador to view this situation fi rsthand and to see how the police there are dealing with this new kind of confl ict—a gang war that, if not contained, could prove to have more far-reaching consequences than the civil war of years past. As with any Latin American country, there is a certain protocol that must be followed. This necessitated our meeting with one of Salvador’s “Top Cops,” Vice-Minister of Security, Rodrigo Avila. Señor Avila is very articulate in both Spanish and English and has a degree from North Carolina State. Avila served as the Chief of El Salvador’s Police for over six years in the 1990s before assuming his current cabinet-level position. He was very hospitable to us while being entirely forthright regarding his country’s current problems.

In February, 2005, the month we were there, there were 255 murders in El Salvador, a country of just six million inhabitants. By all accounts, the majority of this violence (roughly 80%) involved gang-on-gang murders. This is indeed a shocking number, but what is even more shocking is that this is an improvement over previous periods, according to Señor Avila.

The question then becomes, what is being done about this epidemic? To get the answer, we hit the streets, armed with cameras and just enough Spanish to get into trouble. Like any other country in the world, the war on crime is not won in multi-storied government buildings, but in the trenches. The bulk of this responsibility falls on the shoulders of a select few within the Salvadoran police, the Unidad Tactica Operativa or UTO. Jeff and I had the distinct pleasure of riding with these highly professional offi cers during some of their routine gang investigations to observe their weapons and tactics.

Upon fi rst glance, one notices how well equipped they are, especially for a Latin American police force. Each offi cer was carrying his issued semiautomatic handgun with several extra magazines. Although the majority of these pistols were Smith and Wesson models, there was a sprinkling of CZs and Berettas throughout the force as well. Offi cers primarily carried their handgun in some variant of a tactical nylon drop-holster. The only authorized round is the standard NATO FMJ 9mm round, and like many other countries in Central and South America, all hollow-point rounds have been outlawed for several years now.

In addition to their sidearms, each UTO offi cer carries an Israeli-made Galil rifl e. This is an especially popular fi ring platform south of the border and is available in both 7.62mm and 5.56mm. Salvadorans use the 5.56mm versions unlike their counterparts in Colombia, where the 7.62mm is preferred. I observed both the AR versions and the SAR versions during my trip, with the SAR version having a shorter barrel, gas tube and piston. These rifl es are produced by Israeli Military Industries and are based on the reliable Kalashnikov design. Both rifl es are fi tted with folding stocks that facilitate use in confi ned, urban environs and vehicles. The 5.56×45 mm magazines hold 35 rounds, fi ve more than the standard M16/M4 magazines. The 7.62x51mm mags hold 25 rounds. As with the 9mm rounds, only the NATO FMJ rounds are authorized.

Other equipment used by the offi cers included OD green, U. S. Army surplus Load Bearing Equipment (LBE) in the form of belts, harnesses and old M16- style magazine pouches. Thigh holsters were the norm, although there were several different models with nothing appearing standard.

When traveling the lesser-developed countries, one gains a sense of how the local culture operates by observation, since nuances in the local tongue may go unnoticed to the gringo. It was our past experience that instantly drew our attention to the fact that the offi cers were preparing to enter the front lines of the gang war by donning load bearing vests, equipped with eight additional, fullyloaded Galil magazines.

With the clear and increasingly obvious knowledge that neither of us had ever visited San Salvador gang territory, coupled with the “255 murders” statistic still fresh in our minds and the fact that these seasoned offi cers felt they needed over 300 rounds of rifl e ammo each, we rather introspectively began preparing our camera gear. Then a few minutes later, the four fully-armed police and the two fully-UNarmed photojournalists hopped into the back of the ubiquitous Toyota Hilux (basically a 4-door Tacoma in the States) and headed into the barrio.

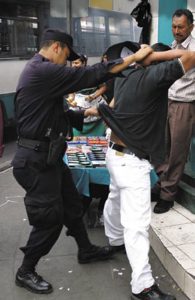

It took an entire thirty seconds upon entering the neighborhood to realize that we were in stone-cold gang territory. Immediately, the UTO offi cers spotted two suspected gang members of the MS organization and became decidedly proactive. With graffi tied walls serving as a backdrop, some offi cers took the “contact” responsibility by patting the individuals down while others with Galils took up perimeter “cover” positions, watching various areas of responsibilities, both at street level and upwards toward the second and third-fl oor balconies that lined the small road. Although the offi cers are very young, it was clear they had the maturity that only comes with experiencing life and death situations. They maintained interval discipline and concentrated on their particular areas of operation, creating a 360-degree ring of coverage.

Operating inside this secured ring, UTO Sub-Inspector Rivera, the leader of our particular unit, identifi ed one of the individuals as a known member of the MS gang based on a rather sophisticated intelligence chart carried by the higher ranking members of the police. These charts show links, titles and responsibilities of various gang associates, along with photos of each. A primary responsibility of the UTO is that of intelligence gathering. Much like organized crime in the U.S., it is often diffi cult to prosecute gang members since many witnesses are so reluctant to testify for fear of retaliation. As such, the local police and prosecutors rely on the intelligence gathering capabilities of the UTO to help build cases against suspected gang members.

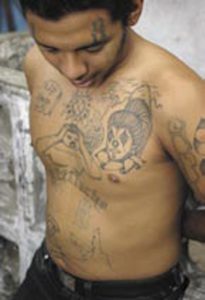

Sub-Inspector Rivera questions the individuals and documents their answers. Then another offi cer produces a digital camera and captures images of the various tattoos so proudly displayed by Salvadoran gang members. Sometimes these tattoos are the only means to identify what is left of a body after a particularly violent rival gang encounter. Salvadoran gang members are particularly liberal with their use of tattoos, oftentimes tattooing their entire face, lips, head and ears. Tattoos have become so synonymous with gangs in El Salvador that the police are specifi cally prohibited from having or obtaining any tattoos whatsoever.

With the stop over, we mount up in the Toyota and are shown some of the gang graffi ti used to mark local territory. Make no mistake, each gang has clearly defi ned their own area and every inch of real estate in the barrio has been claimed by one gang or the other. There is no DMZ— where one group’s tierra ends, the others begin—and this territorial demarcation is not taken lightly by either side. In fact, as I spoke to the various gang members, without exception they viewed a simple encroachment onto their territory by a rival gang member a mandate for killing the violator.

Our afternoon with the UTO offi cers continues, and soon another encounter brings us face to face with “Pee-Wee,” a walking example of one of the diffi – culties the Salvadoran police face when fi ghting the gang problem. Pee-Wee is a member of MS and has spent some time in Arlington, VA before being sent back to his native country. Although UTO and the rest of the Salvadoran police are doing a rather impressive job of getting gang members off the streets (thirty-fi ve of the top fi fty were recently arrested), the United States is deporting Salvadoran gang members faster than the police here can arrest them. Additionally, the level of sophistication of gang activity in the U.S. is typically much higher than that in El Salvador so that when a gang member is deported from the U.S., his experience and prestige from the States vaults him immediately to a position of leadership and power within his respective organization in El Salvador.

One can certainly understand the position of the U.S. deporting illegal aliens involved in gang activities and violent crimes. On the other hand, El Salvador ends up paying the price by being forced to accept some of the most undesirable citizens a country could possibly have. There is no doubt that these gangsters have no respect for human life. Many of them are cold-blooded killers who are way past the point of any rehabilitation. They make their living through illicit means, living by the sword and dying by the sword. As I questioned many of them regarding their goals and dreams for the future, the near-sighted answer always came back the same—they live for the gang, there is nothing else.

UTO photographs Pee-Wee and his various tattoos since he is unknown to the offi cers. They document his name and let him go. Surprisingly, the contact ends in a handshake, as do many of the others we would experience during our time with the police. While UTO “rolls big” and carries enough ammunition for a prolonged fi refi ght, they also show remarkable courtesy and respect to the citizens they come in contact with.

We are walking back to the truck when several UTO offi cers begin shouting and sprinting towards an open-air market. Out of instinct we break into a run to follow the action. It seems they have spotted a known sicario—an assassin. Through the stalls selling brightly colored hammocks, dried fi sh and handicrafts, the police pursue the individual while shouting rapid-fi re Spanish. Although much younger than the offi cers, he is not faster and is quickly caught. He is twenty-one years old and a member of the 18th Street gang. Scars over his chest and stomach tell the story of his violent youth. I count three scarred-over gunshot wounds and one scar that appears to be from the business end of a machete. Two of the gunshots are in the center of his chest and one would think they would have been fatal. (Looking at the placement of the wounds, I cannot help but be reminded of the two-to-the-chest, one-to-the-head “Failure Drill” practiced by law enforcement.) In his short life, he’s developed a reputation for being very effi cient with a knife and has killed at least seven rival gang members. Unfortunately, as is often the case, witnesses are too scared to testify against the assassin and after some more photo-taking and questioning, the police are forced to let him go since no one has been able to obtain an arrest warrant for him. Given the appearance of the life he is leading, he may very well not live long enough to face prosecution anyway.

This is our last encounter of the day and with that, our time with this welltrained unit comes safely to a close with the only shooting having been done with Jeff’s digital camera.

As I write this back in the United States, the dime-sized mosquito bites I received on my arms are almost a memory. It has been two weeks since my return from El Salvador and I am sitting at my desk contemplating what I gleaned from my trip. Gang violence, although a terrible problem in certain concentrated neighborhoods of El Salvador, is actually on the decline due to the proactive and effi cient work by the local police, something that cannot be said in most of the other countries of the world—including many parts of the United States. It should also not discourage the average tourist from visiting what is otherwise a beautiful country.

Hopefully the United States and El Salvador will continue to work hand in hand to combat these gangs since these two countries make up two sides of the same coin.